Fed Policy: Little Clarity After Jackson Hole

by Fixed Income AllianceBernstein

September 09, 2016

Even though the US Federal Reserve acknowledged the stronger case for a rate hike, there seems to be little agreement on a longer-term monetary policy framework. We think this leaves the economy and markets vulnerable to shocks.

Unusually Direct Language from the Fed Chair

The title of this year’s Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City annual symposium at Jackson Hole was “Designing Resilient Monetary Policy Frameworks for the Future.”

Fed Chair Janet Yellen spent most of her opening address discussing the Fed’s monetary policy tool kit, but she also reviewed the current environment and near-term policy path. “In light of the continued solid performance of the labor market and our outlook for economic activity and inflation, I believe the case for an increase in the federal funds rate has strengthened in recent months.”

That’s a very direct statement—unusually so for the Fed leader. And it’s very different from her tone after the June Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meeting, when she was still looking for assurances from the labor market that the economy’s momentum hadn’t fallen off.

Data Dependence: A Flawed Approach?

Since that June meeting, there have been three payroll reports, each with strong gains: 271,000 for June, 275,000 for July and 151,000 for August. The sequence of those gains isn’t particularly important, in our view—hiring patterns are never linear. Overall, the jobs data clearly show that labor markets are generating above-average and fairly large gains.

But will they be enough to spur policy change?

Yellen’s statement indicates that she and the FOMC are navigating policy decisions with a data-dependent approach, reacting to each set of monthly data. We think this approach is flawed. It relies too much on the next economic release, suggesting that new preliminary data is more important than prior reports and the underlying data trend.

Kevin Warsh, a former Fed governor, agrees. Here’s Warsh from a speech this past March:

“As currently practiced, there may be more dangerous words [than ‘data’] in the conduct of monetary policy, but none cited with such frequency or fervor. Let me count its flaws as an operating principle for policy. That which constitutes data for the purposes of policymakers is not contemporaneous. It only becomes ‘data’ when outfits like the Bureau of Labor Statistics or Department [of] Commerce say so.…So, the data sets are anachronistic, backward-looking and subject to massive revisions.”

Looking Beyond the Short Term

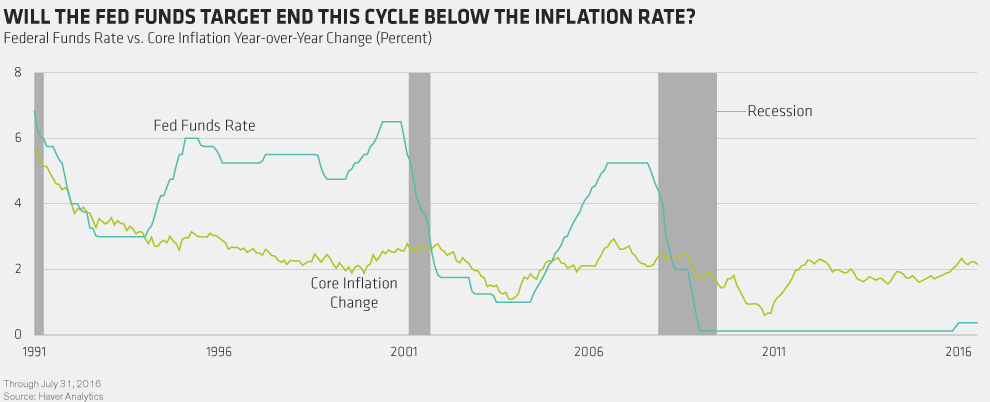

From a longer-term perspective, Yellen discussed whether official rates, which are near zero and well below inflation (Display 1), and other tools provide enough ammunition for monetary policy to be effective in the next downturn. Questions about policy effectiveness stem largely from lackluster growth in this economic cycle and policymakers’ inability to reach and maintain their price target.

Monetary policy has successfully promoted private sector growth—notably in the sectors most sensitive to changes in interest rates and liquidity. Overall private sector growth has averaged 2.8% per year for the past seven years. That’s not spectacular, but growth was hobbled by both the inclusion of a large energy-sector hit over the past year or so and a very slow housing recovery.

Public Sector Headwinds from Lower Government Spending

In contrast to private sector growth, unprecedented reductions in government spending have hampered the public sector, slowing overall gross domestic product (GDP) growth. Since the start of the current cycle in mid-2009, real government spending has contracted by nearly $200 billion. That’s starkly different from the relatively large gains in prior cycles (Display 2).

Government spending puts money directly into the economy; monetary policy doesn’t. The headwind from government spending has made monetary policy look ineffective—but policy has worked in the areas where it matters most.

Inconsistent Treatment of Energy’s Inflation Impact

On the inflation side of the equation, core consumer price inflation (CPI) is running at 2.2%. That’s close to the 2.4% seen at the end of the 1990s economic cycle and the 2.3% at the end of the 2000s cycle. So, the argument that underlying inflation isn’t close enough to the Fed’s inflation target or to the inflation trends of prior cycles isn’t supported by the actual data.

To be fair, headline inflation—currently 0.9%—is far from the target range, mainly because of lower oil prices. Yet policymakers are inconsistent on this topic. When rising energy prices lift headline inflation, some officials argue that costlier energy acts as a tax, reducing cash flow and demand. They believe they shouldn’t respond to this temporary (energy-driven) inflation change. We agree, but the argument should be consistent when cheaper energy reduces headline inflation.

The bigger issue for policymakers is the change in the inflation cycle. Home-price inflation has historically been highly correlated with general inflation. But that’s no longer the case, because of changes in how the housing component of CPI is calculated. That decoupling makes monetary policy less effective against asset-price inflation.

Why does this matter? Because it could be argued that the business cycles of the 1990s and 2000s ended because of an unwinding of asset-price inflation cycles—not general inflation cycles.

Is the Fed Prepared to Fight the Next Recession?

That brings us to the question Yellen raised in her speech: “Would an average federal funds rate of about 3% make it harder for the Fed to fight recessions?”

The Fed chair noted that low expectations for future fed funds rates reflect the Fed’s success in stabilizing inflation at a much lower rate than before. They also reflect the likelihood of a lower long-run neutral interest rate, because potential growth is lower.

We’d make two points about Yellen’s question.

First, the past two business cycles of the 1990s and 2000s ended with core inflation peaking at 2.4% and 2.3%, respectively, not too far from the current 2.2%. But the federal funds rates for those two past cycles were much, much higher, peaking at 6.5% in the 1990s and 5.25% in the 2000s.

Second, while interest rates work to limit inflationary tendencies in the economy, they also impact capital flows. Even with the higher fed fund peaks in past business cycles, we still witnessed two very large misallocations of capital—to the financial and real-asset markets.

In our view, a policy regime that seems to ignore these major capital and asset-price cycles will be ill prepared for the next one.

The views expressed herein do not constitute research, investment advice or trade recommendations and do not necessarily represent the views of all AB portfolio-management teams.

Copyright © AllianceBernstein