Absolute Return Partners Letter

February 2012

The Unlikely Bull Market

by Niels Jensen, Absolute Return Partners

Europe is going from crisis to crisis as the rest of the World is doing its best to muddle through. Meanwhile, global equity markets do not seem to care one jot. They only recognise one direction at present and that is higher. Many investors are perplexed. Fundamentals stink, or so most investors seem to think. Some commentators even talk of a pending equity meltdown of cataclysmic proportions. What on earth is going on?

The bears have a point. Fundamentals are not exactly rosy. I have just returned to the UK from a week in Mallorca where I have had the opportunity to take the temperature of Spain through the local media and through speaking to people on the ground. The picture I was presented with was not pretty.

The latest report from Instituto Nacional de Estadistica suggests that the overall level of unemployment in Spain now stands at 22.85% (see here) and youth unemployment has risen to more than 50%. Although a flourishing black economy in Spain ensures that not all these people are without work, the relentless rise in unemployment is crippling the domestic economy.

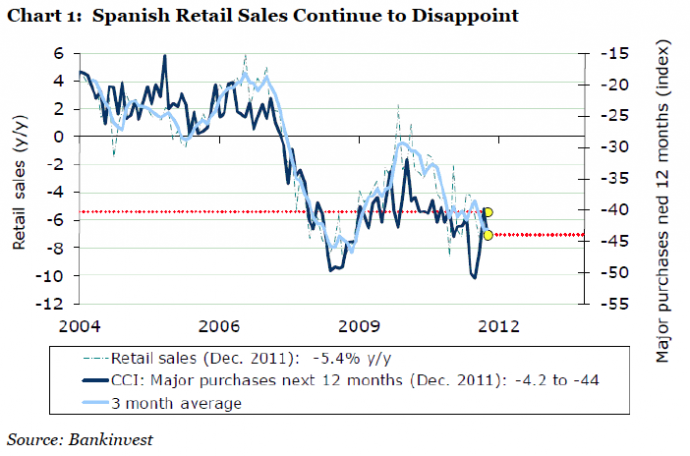

Hardest hit are retail sales. December sales came in 5.4% below year-ago levels (chart 1), confirming the dramatic loss of purchasing power in Spain. Most other macro indicators confirm this depressing trend, suggesting that GDP should in fact be much weaker than it has turned out to be.

The subject of Spanish GDP has intrigued me for a while (I am a sad case, I know). When I began to do research for this letter back in December, the working title was Is Spain Cooking Its Books? Inspired primarily by Frank Veneroso’s excellent work1, I came to the inevitable conclusion that the economic statistics coming out of Madrid simply did not add up2.

Then, on a quiet day between Christmas and New Year when most people had their Bloombergs switched off, the new Spanish government which had come into office only a week earlier, broke the news that the 2011 fiscal deficit would probably reach 8% of GDP - a full 2% over the target agreed with the European Union only a few months earlier (see here).

Embarrassingly, the admission came only four weeks after the outgoing government had confirmed that Spain was very much on target to keep the deficit below the 6% agreed with the EU. So, yes, Spain was cooking its books and Frank Veneroso was absolutely right in raising the red flag, but I had lost a good headline for the February letter. Back to square one.

The other big issue facing the Spanish economy is the blatantly overvalued property assets on the balance sheets of the banks and savings banks (see here). From what I heard whilst in Mallorca, the Bank of Spain is becoming steadily more forceful in its handling of the crisis, demanding a far more aggressive approach as to how the banks mark repossessed properties on their books.

To give you an idea as to how bad the situation is, a 2010 profit of about €50 million in Caja de Ahorros del Mediterraneo turned into a loss of €1.7 billion by June 2011 after its property book was marked to market. And that is just one small savings bank (that has since ceased to exist).

The new government has already put out an estimate of how much they expect (read: request) Spanish banks to set aside in additional provisions against bad property loans - €50 billion or approximately 4% of GDP. If that number proves sufficient, the property crisis is probably manageable. It is certainly not of the magnitude seen in Ireland.

On the other hand, consider this: Spain’s financial system has about €338 billion of property related assets on its books, €176 of which are classified as bad loans. If Fitch is correct in its analysis that the average foreclosed loan in the Spanish banking system is 43% overvalued (see here), then Spanish banks should set aside a lot more than €50 billion in provisions. And property prices continue to fall.

Much of the weakness in Spain, and elsewhere, is blamed on austerity but the facts simply do not support this argument. Most of the countries supposedly in the midst of an austerity drive – including the UK whose government has managed to convince the rest of the world that it is doing all the right things but the facts suggest otherwise – continue to run massive fiscal deficits. Something else must be at work.

In a credit-based economy, which would include pretty much every country currently finding itself in a crisis of sorts, aggregate private sector demand is not only a function of income but also of changes in debt. Proponents of this idea include economists such as Richard Koo and Steve Keen but, despite the logic of their message, it is a concept ignored by many economists. As Steve Keen writes:

“Bizarre as it may sound, these arguments by leading economists ignore decades of empirical research into and practical knowledge on banking, which have established that their fundamental premise is false: a new debt is not a transfer from one bank customer’s account to another’s—which is effectively what Krugman models and Bernanke assumes above — but a simultaneous creation of both a deposit and a debt by the bank. A bank loan thus gives a borrower additional spending power without forcing savers to reduce their spending power to compensate.”3

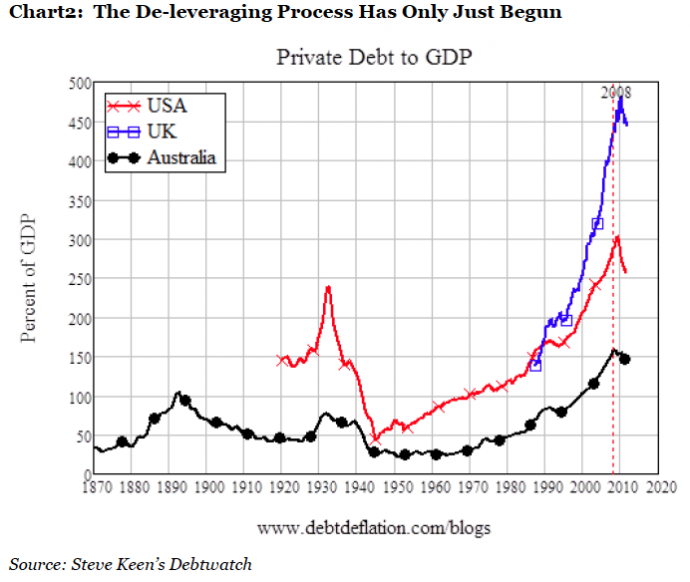

In a highly leveraged economy such as the UK, even modest changes in household leverage can have a profound impact on the economy as the debt reduction absorbs capital otherwise ear-marked for consumption. Chart 2 below illustrates precisely how much private debt has escalated in the UK in recent years and how much de-leveraging is still to come, assuming we need to return to debt levels last seen in the 1980s before the explosion in private debt.

Given those dynamics, and given the bleak prospects of a sustained upswing any time soon in Europe, there are commentators who argue that the ECB should engage in quantitative easing similar to the policy pursued by the Federal Reserve Bank and the Bank of England. To those people I say: Wake up. Where have you been for the past six months? The ECB together with the national central banks of the eurozone have engaged in massive QE since last August (chart 3) although they have done their best to be quite discreet about it.