This article is a guest contribution of Neils Jensen, Absolute Return Partners.

“When data contradicts theory in a discipline like physics, there is excitement amongst scientists […]. When data contradicts theory in finance, there is dismissal.”

Robert Arnott

Active management in the equity field is a notoriously difficult art. In fact so difficult that more and more investors give up and go passive instead. If you can’t beat them, join them. In the US alone, retail investors have withdrawn about $350 billion from active equity managers in the past two years and instead pumped $500 billion into passive investment vehicles (mostly ETFs). Retail investors are not alone. Sovereign wealth funds, endowments and pension funds are all allocating ever larger amounts to passive instruments. By one estimate, some $4 trillion worth of actively managed assets will switch to passive management over the next 5 years(1).

Behind this flight to armchair investing lies a growing realisation that the majority of active managers will never consistently beat the index. Newly published research from Standard & Poors(2) suggests that for the five year period ending 31 December, 2009, only 39% of active large cap managers outperformed the S&P500. In mid- and small-cap, the problem was even more pronounced with only 23% and 33% outperforming the respective benchmarks.

It all began with Harry Markowitz, Eugene Fama and the efficient market hypothesis, developed back in the 1950s. A decade later, when William Sharpe published his work on the capital asset pricing model (CAPM) on the basis of Markowitz’s and Fama’s earlier work, it gradually became accepted that it is near impossible for most mortals to outperform the market (Warren Buffett is obviously not a mere mortal). Hence the foundation for passive investing, index funds and ETFs was laid.

The irony of all of this of course is that ultimately the growth of passive investments will create anomalies and inefficiencies. Stock prices will be driven more by inclusion/exclusion in the indices than by the intrinsic value. For stock pickers, such an environment is likely to create enormous opportunities. But we are not there yet. For the time being, in the equity arena, index products are likely to continue to outperform the majority of active managers.

So why do most active equity managers underperform? Many a research paper has been written on this subject, and I am not particularly keen to add to an already long list. I think it is far more interesting to look for solutions, so I shall answer the question only superficially. The most obvious reason is cost. Between management fees, performance fees (sometimes), trading costs, custody and admin fees, active managers often start the year being behind by 2% or more. Not easy.

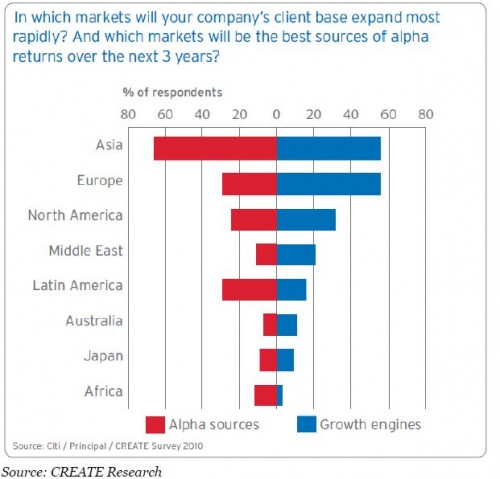

However, cost alone does not explain the difference between active and passive managers; if it did, active managers would consistently underperform and that is not the case. ‘Herding’ is another reason. We are all prone to it. Herding manifests itself in a number of different ways. For example, investors tend to fall in love with the same investment ideas, which can drive valuations up in the short to medium term but cause over-crowding longer term and ultimately lead to a collapse in valuations (think dotcom). In the survey conducted by CREATE Research, asset managers from all over the world were asked which markets would be expected to grow the fastest and which would offer the best opportunities for alpha going forward.

Chart 1: CREATE Research Survey on Market Opportunities

The response, which is shown in chart 1 above, speaks for itself. Not surprisingly, most of us have fallen in love with Asia. It is hard to disagree that Asia looks likely to deliver higher growth than both Europe and North America in the years to come; however, to conclude on that basis that Asia will also offer the best opportunities for alpha may be a step too far. This is an example where unrestricted affection for a particular market may have clouded the minds of investors – a classic example of herding.