It might have seemed great in writing, and it definitely prevented a deeper recession, but China’s large policy stimulus might however be a drag on development.

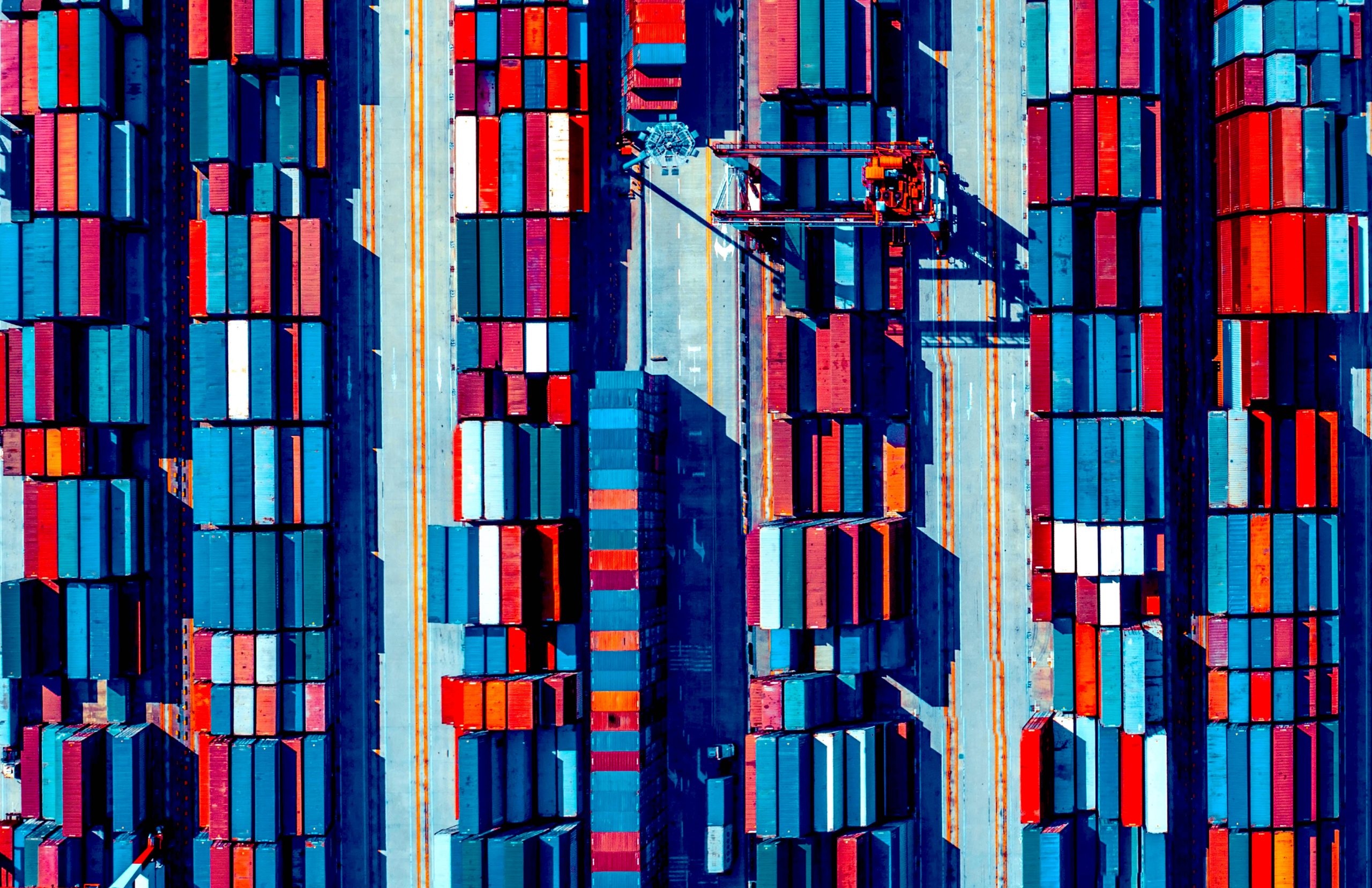

For more than ten years, the central government has put strict limits on the capability of nearby governments to borrow cash. But, to avoid these limits, local governments have increasingly set up local investment companies, referred to as LICs, and when credit policy was eased in 2009, these LICs raised debt at an apparently mad pace. What amount of cash did they raise? Controversy rages over whether the actual amount is 6-trillion yuan or 11-trillion yuan. However the argument is actually also missing the point. The two numbers happen to be huge, and, far more considerably, the end result depends greatly upon precisely how as major a portion may become non-performing loans during the coming several years.

Research from the International Monetary Fund of banking crises in 37 countries puts the median peak in non-performing loans at 22 per cent of total loans. By comparison, if only half the smaller 6-trillion yuan estimate outcomes in poor loans—the most optimistic forecast—this would still represent a sizeable 10-percent of total loans, with the actual figure likely to be higher.

Are these claims poor news for the country's economy?

It's definitely not the very first time China has confronted such a concern. In 1999, China bailed out its banks, purchasing 1,400-billion worth of non-performing loans. The bailout equated to 16 per cent of GDP, a similar figure to today’s estimates. But robust nominal GDP, averaging 14 per cent for a lot more than a decade, had reduced that figure to a paltry 4 per cent of GDP by last year, regardless of recovery rates.

The lesson is clear. It's China’s capability to rapidly bring its LICs to order and create an additional decade of robust nominal GDP development which will determine its chances of escaping today’s mess. So long as today’s NPLs are frozen at their current levels, they will appear far smaller in time.

However, you will find problems. To begin with, China was kept floated on strong global demand throughout the 10 years following 1999. It not benefiting from the same support these days as Europe and also the US reduce debt. Second, the LICs warn from the limits to fiscal stimulus. It's not clear whether China could, or would be willing, to commit to an additional round of fiscal stimulus given the consequences from the last. And although the risks of the double-dip within the global economy are far smaller, the chances of a property market correction aren't, meaning a lot more fiscal stimulus might however be required.

The LICs also underscore the deep-rooted difficulties within the financial marriage between the local and central governments. However, China is hoping that domestic demand, particularly within the interior provinces, will drive economic development more than the next decade. If so, then finding a sustainable method to fund nearby governments will be crucial to meeting that objective.

Background indicates China will succeed. But a sudden slowing in nominal GDP development, or a failure to prevent the LICs from investing in a lot more white elephant ventures and generating a rising tide of poor loans, will make today’s difficulties far harder to digest than those a decade ago. So regardless of whether the true figure is 6 trillion yuan or 11 trillion yuan, there remains great reason for concern.