Deciphering Negative Yields

by Anthony Valeri, Fixed Income and Investment Strategist, LPL Financial

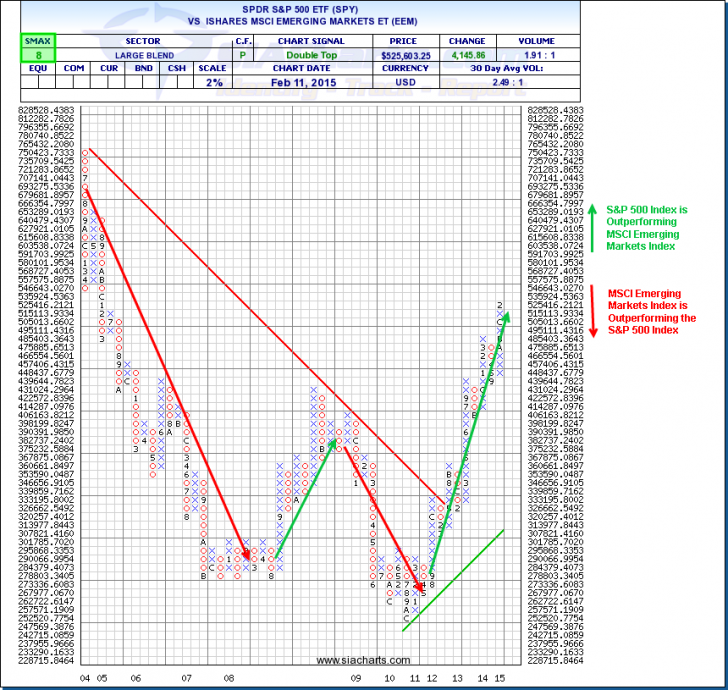

Record low bond yields are one thing, but yields with a minus sign in front of them truly catch investors’ attention. Nine countries now have bond markets that offer negative bond yields. The presence of a negative yield among very short-term securities, such as a three-month obligation, has occurred on occasion. During times of market turmoil in the U.S., one- and three-month T-bill yields have dipped into negative territory for a brief period of time. However, in Europe, negative yields have spread across short-term maturities and into intermediate maturities [Figure 1].

Negative yields are usually prevalent only on top-quality government bonds, but last week witnessed the first negative bond yield on a newly issued corporate bond. Nestle issued a two-year bond that sold at a -0.05% yield. Apple recently announced it may issue bonds in Swiss Francs to take advantage of negative yields. Covered bonds, bonds that are issued by European financial institutions backed by high-quality assets and usually AAA-rated, began trading with negative yields in October 2014, but the first negative corporate yield is new.

A central bank determined to drive interest rates lower is one, but not the sole, driver of negative bond yields. In the case of the European Central Bank and Swiss National Bank, overnight borrowing rates are negative and create the starting point for negative bond yields. Both central banks are purposely making it punitive to hold cash. In the case of the ECB, the goal is to spur bank lending. Negative overnight borrowing rates usually only impact the very shortest maturities.

An extension of negative yields into intermediate maturity bonds usually reflects a likelihood of deflation, recession, or both. In Europe, all three factors (central bank, deflation, and recession risk) are at play and explain the persistence of negative bond yields.

Negative bond yields also entice investors to invest in other securities. In the case of negative short-term yields, central banks are trying to motivate investors either to buy positive-yielding longer-term bonds, which may bring down longer-term borrowing rates, or buy greater risk investments such as corporate bonds or even stocks.

Such aggressive central bank policy can buoy financial markets. The decline in long-term German Bund yields is an example that suggests the ECB’s medicine is working. (For more on Europe, see this week’s Weekly Economic Commentary, “Europe: The Road to Recovery?”) The goal, particularly with respect to staving off deflation, is to boost consumers’ and investors’ inflation expectations. Inflation expectations in Europe have increased in recent weeks.

Reasons To Buy Negative Yields

A few reasons why an investor would buy bonds at negative yields, as perplexing as that may seem, include:

• Deflation risks. If the buying power of a nation’s currency is expected to weaken, bonds, even at negative yields, may provide some protection. For example, if deflation is running at a 1% rate, a -0.5% yield can offer some protection. Simply holding cash would therefore result in a 1% decline in purchasing power where as a bond would limit that decline to -0.5%. But this is hardly consolation and still a money losing option if holding to maturity. This is a dire rationale and only taken to protect against extremely negative outcomes.

• Desirability for foreign investors. Investors looking to avoid deflation, or depreciation of their home currency, may invest in bonds of a negative-yielding country if they believed their home currency would depreciate relative that country’s currency. For example, a bond may yield -0.5%, but if home currency depreciation exceeds that amount, a foreign investor’s return would be positive. Eurozone investors may prefer Danish or Swiss government bonds (non-euro denominated) for this exact reason.

• Yield curve dynamics. Higher yields on longer-term bonds offer potential for positive total returns for investors. For example, consider a hypothetical situation where two- and three-year bonds may yield -0.25% and -0.10%, respectively. If interest rates do not change, buying a three-year bond, and holding for one year, may result in a higher price as it becomes a two-year bond and enters a lower, more negative-yielding (-0.25%) environment. The now lower yield may boost the price of the bond, all else equal. This strategy of “riding the yield curve” is common across global bond markets, whether yields are positive or negative, and offers a way to take advantage of upward-sloping yield curves.

• Still higher prices. Momentum can be a powerful force in investing and the expectation of still higher prices can be a motivator. Should deflation become worse or a recession develop, bond prices may rise further and yields may fall more into negative territory. Alternatively, a central bank cutting overnight lending rates deeper into negative territory can also boost the price of a negative yielding bond. When the Swiss National Bank further cut overnight borrowing rates to -0.75%, from -0.25% in January 2015, Swiss government bonds benefited with prices moving notably higher.

Of course, for most U.S. domiciled investors, these reasons are likely not nearly compelling enough to purchase a bond with a negative yield. However, it does highlight a point raised in last week’s Bond Market Perspectives that over the short term, price movements, not yield, may have a more dominant impact on bond performance. The negative bond yield club is exclusively comprised of European issuers reflecting the ongoing deflationary environment, poor growth expectations, euro currency risks, and prevalence of negative overnight borrowing rates at selected central banks. With economic growth in the United States tracking near 3% in 2015 and the Federal Reserve on track to potentially raise rates later this year, U.S.-based investors do not face the same negative overnight borrowing rates, recession threat, or currency risks of European-based investors. Nonetheless, negative yields in Europe continue to highlight the relative bargain U.S. bonds are on a global basis and why the rise in interest rates in the U.S. is likely to be gradual.

IMPORTANT DISCLOSURES

The opinions voiced in this material are for general information only and are not intended to provide specific advice or recommendations for any individual. To determine which investment(s) may be appropriate for you, consult your financial advisor prior to investing. All performance reference is historical and is no guarantee of future results. All indexes are unmanaged and cannot be invested into directly.

The economic forecasts set forth in the presentation may not develop as predicted and there can be no guarantee that strategies promoted will be successful.

All investing in includes numerous specific risks including: the fluctuation of dividend, loss of principal and potential illiquidity of the investment in a falling market.

Bonds are subject to market and interest rate risk if sold prior to maturity. Bond values and yields will decline as interest rates rise, and bonds are subject to availability and change in price.

Government bonds and Treasury bills are guaranteed by the U.S. government as to the timely payment of principal and interest and, if held to maturity, offer a fixed rate of return and fixed principal value. However, the value of fund shares is not guaranteed and will fluctuate.

Investing in foreign fixed income securities involves special additional risks. These risks include, but are not limited to, currency risk, political risk, and risk associated with foreign market settlement. Investing in emerging markets may accentuate these risks.

High-yield/junk bonds are not investment-grade securities, involve substantial risks, and generally should be part of the diversified portfolio of sophisticated investors.

Currency risk is a form of risk that arises from the change in price of one currency against another. Whenever investors or companies have assets or business operations across national borders, they face currency risk if their positions are not hedged.

Copyright © LPL Financial