by Monevator

The low volatility phenomenon is described as an anomaly; like ball lightning or a dog that says “sausages” or sexy popes, it shouldn’t work but it seemingly does.

The promise of low volatility equities is three-fold:

- Returns that match or exceed the market over time…

- …while inflicting around 20% less price fluctuation pain upon investors, and…

- …during a bear market nightmare, total losses that are less severe than the market as a whole.

It sounds too good to be true. The same or better returns for less risk? Yes please, I’ll have some of that.

Most investors will be aware that financial theory warns that you don’t get something for nothing. There’s no reward without risk they say, and so more volatile investments should offer greater expected returns than safer options. Except they don’t.

Low volatility equities have been shown to outperform their high vol peers, offering superior risk-adjusted returns over the course of the last 40 years.

And that’s as weird as a catfish playing with yarn. What are we doing stocking our portfolios full of shares that are about as stable as dynamite when we could get the same results for much less trouble?

The low down

Low volatility is another of the return premiums that concentrate on certain company traits to produce something like a genetically modified super-crop of equities – with the potential to increase the return of your portfolio.

In this case, the low volatility bracket is filled with companies that are relatively less affected by the movements of the broader stock market.

These are known as low beta companies. When the stock market takes a tumble, their prices won’t necessarily fall so far in tandem.

An example of a low beta equity is a power company. Customers still need to keep the lights on even during a recession, so the firm and its share price may be less badly hit than say a car manufacturer when the wider economy heads south.

Equally, if there’s a raging bull market, the utility firm will benefit from the general upswing in demand. But it’s unlikely to get as big a bounce as the car company with its new line of robot-chauffeured roadsters.

The upshot is that low volatility strategies tend to underperform during the good times and outperform during the bad.

Humans don’t learn

None of this explains why sluggish shares should out-perform high beta (that is, high volatility) shares that experience more ups and downs than an elevator operator.

For that it seems we must once again turn to our dumb human brains.

There are a number of theories from behavioural finance that might explain why we accept higher prices and lower returns when buying high volatility equities:

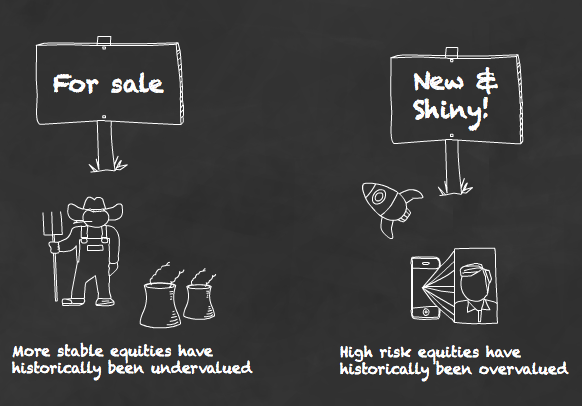

- We love a lottery. We’d sooner gamble on an overpriced tech company that’s never made a bean in the hope that it might become the next Google than we would invest in some boring dog food cannery that will keep making profits as long as people don’t want to starve their dogs.

- Overconfidence means we’re convinced we can pick the next Google out of the crowd, even though we know most investors don’t have this skill and most ‘next Googles’ turn into the last GeoCities.

- Optimistic analyst forecasts for fast-growing equities serve to push up prices and consequently lower future returns.

- Active fund managers dare not tilt towards low volatility equities for fear that they’ll get fired when they deviate from their benchmark for a prolonged period.

- We’re not all Sages of Omaha. One way to exploit the low volatility anomaly is to load up on less risky equities and then pump your returns with leverage. ++ Alert ++ Alert ++ Compulsory Warren Buffet reference: Warren Buffet apparently does this with his insurance company float. ++ End Alert ++ But many investors are prone to leverage aversion. They’re either not allowed (pension funds) or too afraid (me!) to take on the risks, costs, and hassle of borrowing to invest. So instead they lean on high beta assets for extra snap, crackle, and pop but that dependency raises prices and reduces future returns.

A low ebb

Human behaviour being what it is (i.e. mentally frozen in the Paleolithic), there’s good reason to believe that low volatility may survive the ravages of arbitrage as has momentum.

For instance despite the anomaly’s discovery in 1972, low volatility beat the US market by 2% per year between 1963 and 2009, while exhibiting 15% less risk.

However, like all the return premiums, low volatility is not an escalator to dreamland. There’s no guarantee it will outperform in the future and there’s a near certainty that it will underperform for years at some point – testing your will and sanity when it does so.

Indeed, the irony of low volatility’s recent popularity (and the proliferation of supporting tracker products) is that low vol equities may have become significantly overvalued.

As always, when an investing strategy becomes a fad, then there’s a heightened danger that it’s due a strong dose of underperformance.

We’ll explore that problem and a few of the other controversies surrounding low volatility in the next post.

Take it steady,

The Accumulator

Copyright © Monevator