by David Merkel, Aleph Blog

In late 2007, I was unemployed, but had a line on a job with a minority broker-dealer who would allow me to work from home, something that I needed for family reasons at that point. The fellow who would eventually be my boss called me and said he had a client that needed valuation help with some trust preferred CDOs that they owned.

Wait, let's unpack that:

CDO — Collateralized Debt Obligation. Take a bunch of debts, throw them into a trust, and then sell participations which vary with respect to credit risk. Risky classes get high returns if there are few losses, and lose it all if there are many losses.

Trust preferred securities are a type of junior debt. For more information look here.

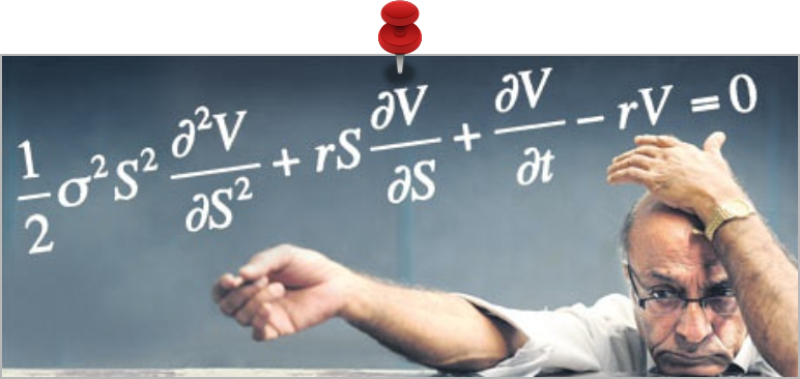

I got to work, and within four days, I had a working model, which I mentioned here. It was:

- A knockoff of the KMV model, using equity market-oriented variables to price credit.

- Uncorrelated reduced discrepancy point sets for the random number generator.

- A regime-switching boom-bust cycle for credit

- Differing default intensities for trust preferred securities vs. CMBS vs. senior unsecured notes.

It was a total scrounge job, begging, borrowing, and grabbing resources to create a significant model. I was really proud of it.

But will the client like the answer? My job was to tell the truth. The client had bought tranches originally rated single-A from three deals originated by one originator. There had been losses in the collateral, and the rating agencies had downgraded the formerly BBB tranches, but had not touched the single-A tranches yet. The junk classes were wiped out.

Thus they were shocked when I told them their securities were worth $20 per $100 of par. They had them marked in the $80s.

Bank: "$20?! how can they be worth $20. Moody's tells us they are worth $85!"

Me: "Then sell them to Moody's. By the way, you do know what the last trade on these bonds was?"

B: "$5, but that was a tax-related sale."

Me: "Yes, but it shows the desperation, and from what I have heard, Bear Stearns is having a hard time unloading it above $5. Look, you have to get the idea that you are holding the equity in these deals now, and equity has to offer at least a 20% yield in order attract capital now."

B: "20%?! Can't you give us a schedule for bond is worth at varying discount rates, and let us decide what the right rate should be?"

Me: "I can do that, so long as you don't say that I backed a return rate under 20% to the regulators."

B: "Fine. Produce the report."

I wrote the report, and they chose an 11% discount rate, which corresponded to a $60 price. As an aside, the report from Moody's was garbage, taking prices from single-A securitizations generally, and not focusing on the long-duration junky collateral relevant to these deals.

In late 2008, amid the crisis, they came back to me and asked what I thought the bonds were worth. Looking at the additional defaults, and that the bonds no longer paid interest to the single-A tranches, I told them $5. There was a chance if the credit markets rallied that the bonds might be worth something, but the odds were remote — it would mean no more defaults, and in late 2008 with a lot of junior debt financial exposure, that wasn't likely.

They never talked to me again. The bonds never paid a dime again. I didn't get paid for running my models a second time.

The bank wrote down the losses one more time, and another time, etc. How do you eat an elephant? One bite at a time. It did not comply well with GAAP, and eventually the bank sold itself to another bank in its area, for a considerably lower price than when they first talked to me.

So what are the lessons here?

- Ethics matter. Don't sign off on an analysis to make a buck if the assumptions are wrong.

- Run your bank in such a way that you can take the hit, rather than spreading the losses over time. (Like P&C reinsurers did during the 1980s.) But that's not how GAAP works, and the CEO & CFO had to sign off on Sarbox.

- A model is only as good as the client's willingness to use it. There are lots of charlatans willing to provide bogus analyses — but if you use them, you know that you are committing fraud.

- Beware of firms that won't accept bad news.

I don't know. Wait, yes, I do know — I just don't like it. This is a reason to be skeptical of companies that are flexible in their accounting, and that means most financials. So be wary, particularly when financials are near or in the "bust" phase — when the credit markets sour.

Copyright © David Merkel, Aleph Blog