GDX: What The Heck Happened?

By Dave Nadig, IndexUniverse.com | July 23, 2013

If you’re like some gold bugs I know, you thought buying the cow was a great gold strategy. Unfortunately, you probably got killed.

The problem, of course, comes down to cost of production. According to Joe Foster at Van Eck (issuers of the popular gold miners ETF, GDX), the average cost of production across the industry is roughly $1,050 per ounce, with the marginal cost for a smaller mine being much higher than that.

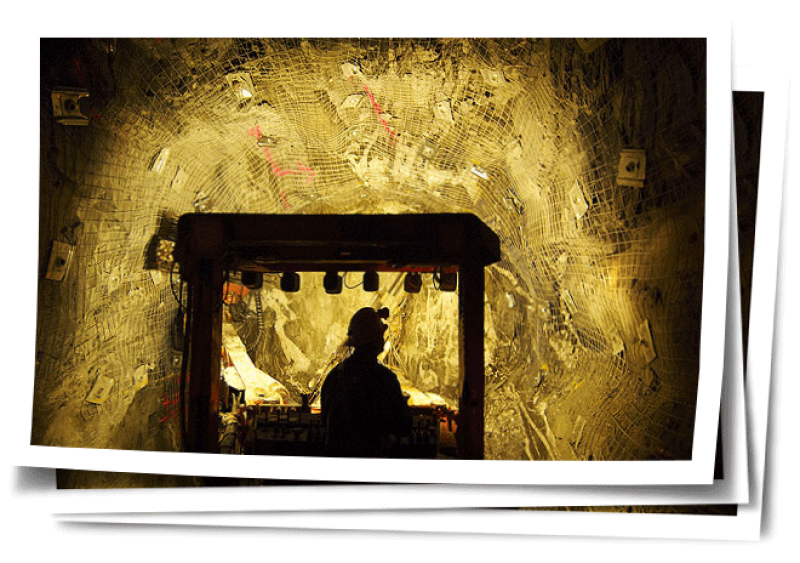

Unlike most industries, there’s very little a mine can do when the price of its product falls below the price of its manufacturing. The realities of the business are simply crushing: All the “easy” gold has long since been dug out of the ground, and any incremental new gold will come at a higher price, deeper in the ground, less pure and harder to process than what they dug out yesterday.

In fact, a new way of calculating the true cost of sustainable mining promulgated by the World Gold Council would put the average price of gold production closer to $1,400, well below the current price.

This crippling environment has forced two things to happen in the gold miner space. Big firms made big investments based on an endless gold-bull market. Barrick started the trend in 2006 when it bought Placer Dome Inc. for $10.2 billion, but it didn’t stop there—virtually all the majors have used flush coffers to buy new mines or rival mining companies.

And virtually all of the major miners have been forced to take monstrous write-downs on those assets. And junior miners like Golden Minerals were forced to simply shut down until prices rebound.

The impact of declining gold prices on miners can’t really be overstated. Just look at the five-year performance of the two major gold mining ETFs versus GLD:

The hate for the miners started long before the price of gold really came down, and for good reason. For decades, investors had used miners as a proxy for gold exposure—after all, once upon a time, you couldn’t legally own gold bullion.

The companies ran enormous hedging operations and paid consistent dividends. But over the last decade, miners systematically got out of the futures market, and started relying on the open market for gold sales. The theory is that this would tie their performance even more tightly to the price of gold. When gold went up, they looked like geniuses, but instead of using their flush bankrolls to pay big dividends, they bought mines at inflated prices.

And now here we are. With no hedged sales to rely on, there are over-inflated assets, extremely (even by Wall St. standards) well-paid management, and minimal dividend payouts. In short, these look like battered and beleaguered companies, which has everyone trying to call the bottom. In fact, we saw phenomenal flows into GDX as things really turned south in June:

So why all the money piling in? Obviously, there’s a classic story of trying to catch the falling knife and call the bottom. But there’s also an interesting dynamic at work. The worse things get for miners as a group, the more mines will shut down and the more assets will be written off.

This incredible accounting and operational purge guarantees pretty much one thing: supply shortages in the future. And with supply shortages come higher gold prices, and another opportunity for the surviving, financially viable miners to leg up faster than the price of gold.

Personally, I’m still not interested in owning the miners—as individual companies, I’m not convinced they’re particularly well run, having grown fat off the market in the last decade. They seem to get hedging exactly wrong, invest in hard assets at market-top prices, and overcompensate mediocre managers.

That’s always the problem with “buy-the-cow” commodities plays: At the end of the day, you’re still investing in people.

At the time this article was written, the author held no positions in the securities mentioned. Contact Dave Nadig at dnadig@indexuniverse.com.