by Patrick Watson, Mauldin Economics

Just as an army moves on its stomach, an economy moves on ships, trucks, and planes. They carry the goods whose purchase adds up to growth.

Nowadays many goods are digital, delivered electronically. But we still need lots of physical stuff which must travel to the customer.

Fewer goods in motion mean lower growth… and that’s exactly what is happening.

With technology, businesses have grown adept at managing inventory. Goods don’t typically sit on store shelves very long. Retailers stop ordering quickly when demand falls.

Lower freight volume is a symptom of a disease that’s getting worse.

Falling Freight Rates

Last summer, the nation’s overheated highways were crammed. Truckers had all the business they could handle as companies rushed to import Chinese goods ahead of expected tariffs.

I said at the time it would end badly. Sure enough, now truckers are struggling with excess capacity and lower volume. Freight rates have dropped hard this year.

Some smaller trucking companies have declared bankruptcy while bigger ones like Knight-Swift and Schneider have cut their annual forecasts. Several Wall Street analysts have downgraded J.B. Hunt, one of the biggest players.

It’s not just trucks, either. Container ship lines, railroads, warehouse operators—the entire logistics industry is starting to contract. You can see it in these recent Wall Street Journal headlines…

- Freight Operators Slowed Hiring in May on Weaker Shipping Demand

- Union Pacific Says Uncertainty, Harsh Weather Driving Down Rail Shipments

- Trade Tensions Worry Ship Operators

- Imports at Southern California Ports Fell Sharply Last Month

This was perfectly predictable. The 2018 transport boom didn’t represent higher demand for imported goods. It was future demand, pulled forward in time. President Trump’s tariff threats gave importers incentive to rush, and they did.

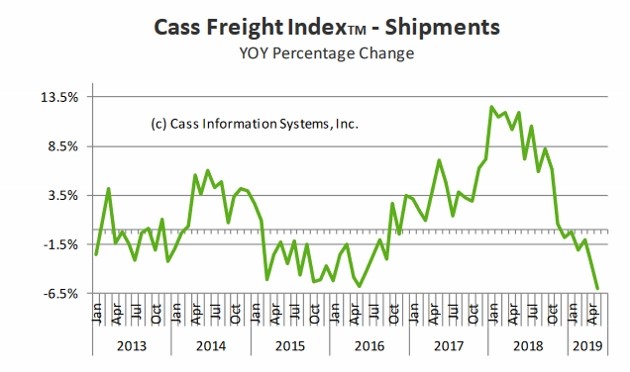

Now the future is here. Shelves are full, so traffic is no longer growing as much, and in some segments it’s falling. The widely regarded Cass Freight Index shows declining year-over-year volume for the last six consecutive months.

Spilling Over

Excess stockpiles of imported goods aren’t the only sign of slowdown. Manufacturing activity is also slowing, both in the US and elsewhere.

This month the IHS Markit Purchasing Managers Index for US manufacturing activity dropped to its lowest level since September 2009, when the economy was in recession. Now it is only a fraction away from signalling an outright contraction.

This might explain an otherwise odd headline I noticed recently: “North American robot orders down in Q1.” The title refers to industrial robots, the kind that have been taking human jobs.

That trend seems to be slowing… which is what you would expect if factories have plenty of capacity to meet current demand.

Worse, the manufacturing weakness is spilling over into the rest of the economy. Here’s IHS Markit chief economist Chris Williamson:

Recent months have seen a manufacturing-led downturn increasingly infect the service sector. The strong services economy seen earlier in the year has buckled to show barely any expansion in June, recording the second-weakest monthly growth since the global financial crisis.

All these comparisons to 2008 and 2009 are more than a little chilling. I remember those years pretty well, and they weren’t fun. To now see similar conditions is, at the very least, not good and possibly very bad.

Meanwhile, Wall Street thinks a magical solution will appear.

Delayed Recession

A lot of this is connected to the ongoing trade war, but not all. The economic expansion would probably be nearing its end anyway. Growth cycles rarely last as long as this one has.

Here’s my theory. The economy should have entered recession a year ago. The late-2017 tax cuts bought a little time by encouraging business investment, while the Fed’s rate hikes made homebuyers rush to beat rising mortgage rates.

Then, the Trump trade fight sparked an import boom that created more activity and jobs. That extended the growth a little more. But those effects were temporary, and now they’re running out.

Some investors think the Fed will pull a rabbit out of the hat by cutting rates again. But access to credit isn’t the problem. Businesses that want to borrow can do so on good terms. The problem is they don’t need to borrow unless they are growing, and they’re not. The Fed can’t fix that.

Shipping weakness is an early warning sign. It doesn’t mean recession is imminent, but the longer it lasts, the more certain we can be that the weakness will spread.

Here’s how Cass says it in its latest report.

- “The freight markets, or more accurately goods flow, has a well-earned reputation for predictive value without the anchoring biases that are found in many models which attempt to predict the broader economy.”

- “The volume of freight in multiple modes is materially slowing and suggests an increasingly bearish economic outlook for the U.S. domestic economy.”

- “With the -6.0% drop in May, we see the shipments index as going from ’warning of a potential slowdown’ to ’signaling an economic contraction.’”

Again, the timing is hard, but it can happen fast. Well into 2008, the economy was already in recession, but we realized it only later. By October, there was no doubt.

Let’s hope 2019 is different.

Copyright © Mauldin Economics