by Sonal Desai, Ph.D. Executive Vice President, Chief Investment Officer, Franklin Templeton Fixed Income, Franklin Templeton Investments

These latest European Parliamentary elections can best be described as inconclusive—as is often the case with European Union (EU) affairs. There is something for everyone. Populist parties did a lot better than in previous rounds, but not as well as they had hoped and others had feared.

In the United Kingdom, Nigel Farage’s Brexit Party won 31.6% of the vote and secured 29 seats (improving on UKIP’s 2014 performance of 27.5% of votes and 24 seats), but some commentators say the vote represented a victory for the remain camp.1 (If the remain camp did win, I suspect “better late than never” may not apply in this case).

In Italy, the right-wing populist Lega boosted its support to about one third of the vote, but its populist coalition partner Five Star lost ground. In France, Marine Le Pen’s far-right party did very well, but so did Macron’s centrist movement.

The bottom line is that these elections leave the European Parliament more fragmented, and confirm that the decades-long European integration process has stalled. Determination to maintain political sovereignty at the national level has gotten stronger; the adoption of the euro has failed to foster the envisioned economic convergence across member countries. This leaves the euro area more exposed to the risk of financial shocks. And it leaves the European Central Bank (ECB) hamstrung, its monetary policy hostage to fiscal dominance.

Widening Gaps in Debt Levels

To say that economic convergence has failed to materialise is putting it mildly. In some important dimensions, euro-area countries have diverged further. Government debt ratios have moved farther apart even as debt levels increased across the board: in 2000, only five member countries exceeded the 60% of gross domestic product (GDP) Maastricht ceiling2; today 11 do. Italy, Belgium and Greece entered the euro area with debt ratios just above 100% of GDP. They have now been joined by Portugal and Cyprus; and while Belgium’s debt ratio declined marginally, Italy’s has surged to more than 130%.

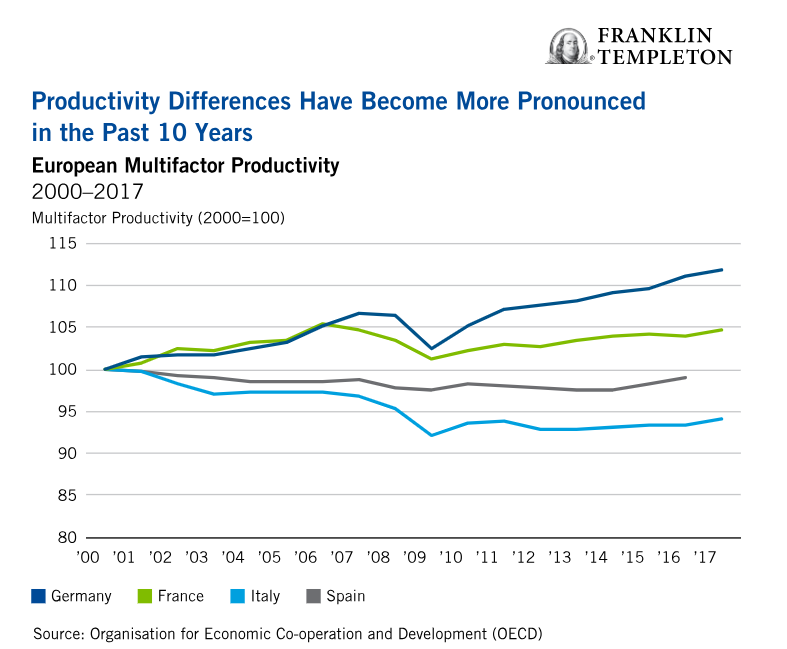

Productivity trends have also diverged. Between 2000 and 2017, multifactor productivity rose by 5% in France and 12% in Germany, but declined by 6% in Italy (and stagnated in Spain).

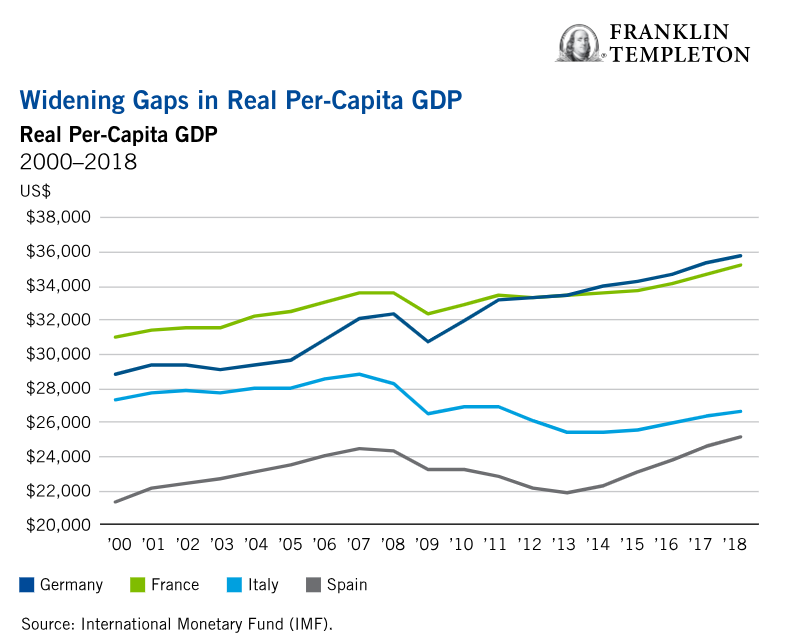

This divergence in productivity growth has pulled living standards further apart. Germany’s per-capita GDP pulled ahead of France. Italy‘s per-capita GDP was just 5% below Germany’s in 2000; today it’s 26% lower.

Italian Growth Has Stalled

How did we get here? The euro area’s formal convergence mechanisms have failed—or rather, proved insufficient. The Maastricht criteria imposed a 3% of GDP limit on budget deficits to enforce budgetary restraint across the area. But what has put Italy’s debt sustainability in jeopardy over the past 10 years is not lack of fiscal responsibility—it’s lack of economic growth.

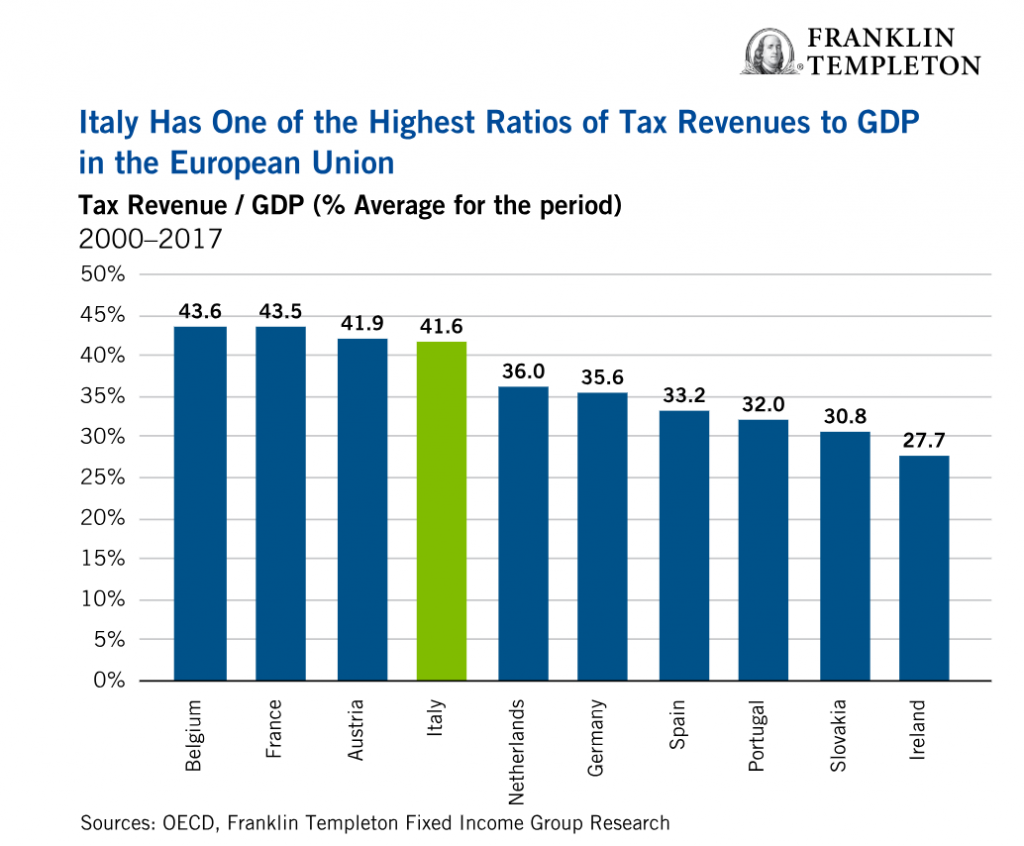

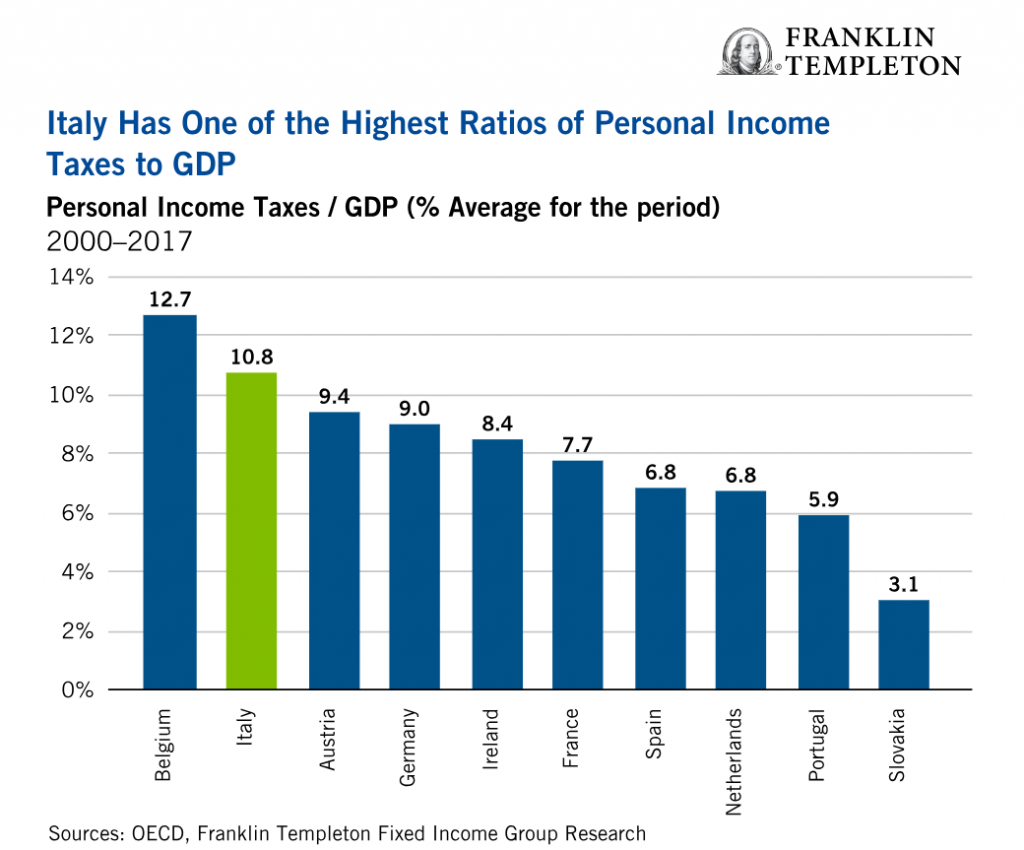

Italy has run a quite prudent fiscal policy over the past decade—unintuitive as that might seem. After the 2009 recession, its primary surplus averaged 1% of GDP, well above other major euro-area members. Its overall budget deficit averaged just under 3% of GDP. And for all the talk of tax evasion, Italy has one of the highest tax revenue ratios in Europe:

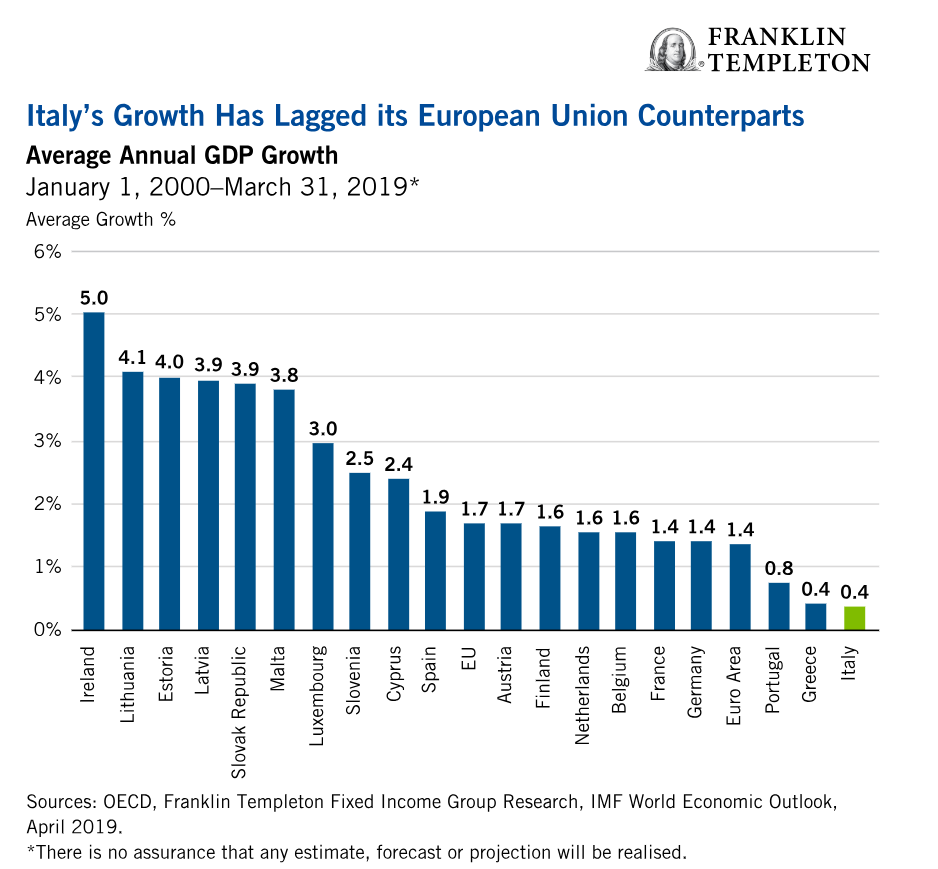

But growth has been missing in action. GDP growth has averaged a mere 0.4% over the past 20 years (2000-19), and Italy’s real per-capita GDP is still below its 2000 level—living standards are no higher today than they were nearly 20 years ago. In a low-inflation environment with monetary policy outsourced to the ECB, and with no political room for an even tighter fiscal policy, the only way out of Italy’s debt trap would be via stronger economic growth.

Since I noted that Italy’s fiscal policy has been prudent over the past 10 years, let me be clear: I am not saying that Italy’s poor growth performance has been caused by German-dictated austerity.

A number of economists and journalists like to argue that Germany’s insistence on fiscal discipline has condemned Southern Europe to stagnation. I completely disagree. How did Italy end up with a 130% of GDP debt ratio? By running a lax fiscal policy for decades prior to euro accession; a lax fiscal policy that left the country with a heavy debt burden and near-zero potential growth.

Looser fiscal policy is manifestly not the answer. As an aside, Spain, which abided by the same fiscal rules, enjoyed average growth of over 3% per year during 2015-18 (about three times faster than Italy), thanks to ambitious reforms implemented after the euro-area debt crisis of 2012-13.

There Is no Substitute for Structural Reforms

Boosting growth requires structural reforms: improving the business environment, making the labour market more flexible, streamlining the public sector. Unfortunately, Italy seems to be suffering from reform fatigue without ever having attempted the serious economic reforms it needs.

Italy’s inability to tackle deep-seated structural issues creates the most high-profile financial risk in the euro area, as only extremely low interest rates can keep Italy’s debt on a sustainable path. But it is by no means an isolated case: France’s reform efforts have also triggered a popular backlash, in turn raising questions about implementation.

Against this divergence in economic performance and living standards, the immigration crisis inevitably deepened divisions and heightened political tensions. When German Chancellor Angela Merkel announced in 2015 that Germany would welcome one million refugees, triggering a sudden surge in immigration to Europe, many argued that an influx of young immigrants could help offset the challenge of Europe’s population aging. But the influx hit the shores of Southern European countries with youth unemployment rates in excess of 30%. A backlash was inevitable.

This latest round of European elections confirms that revamping the integration process will be all but impossible for the next several years.

That does not mean that disintegration becomes inevitable. Popular support for EU membership remains strong across most countries; in these elections, most Eurosceptic parties campaigned on a commitment to change Europe from within, not to abandon it. European governments know well that a breakup of the common currency area would impose exorbitant economic costs and I believe they will do everything they can to avoid it—including if Italy were to come under market pressure.

ECB Trapped by Fiscal Dominance

Many have wondered if and how these elections will affect the choice of who will replace Mario Draghi at the helm of the ECB later this year. More important in my view is that the ECB seems destined to have its room for maneuver constrained by fiscal dominance. With five countries shouldering debt ratios above 100% of GDP, and 11 countries above 60%, (and overall euro-area debt at 85% of GDP) higher interest rates would weigh heavily on member countries’ budgets—and push Italy into an even more precarious position.

Low inflation and low inflation expectations make the issue less pressing for now. Still, it’s significant that at the first signs of growth decelerating from a pace well above potential, the ECB quickly moved to a more accommodative stance, extending its liquidity support to the banking sector.

The ECB has always been more hawkish (or perhaps more accurately, less dovish) than the US Federal Reserve (US Fed). While the Fed kept a wary eye on employment and (albeit without explicit acknowledgement) on stock prices, the ECB focused on its single mandate, the close-to-but-below-2% inflation target it kept overshooting until the financial crisis a decade ago.

Now the tables have been turned. I know markets have priced out any Fed rate hikes for the year. I still disagree. But even if you take the consensus view, the fact remains that the Fed has raised interest rates nine times—from effectively zero to 2.5%—and started shrinking its balance sheet, whereas it now looks like the ECB might get to the end of this economic expansion cycle with negative policy interest rates. I don’t see that changing. It looks like the Fed and the ECB have traded places in a way that should impart a bearish bias to the euro—an important consideration for investors.

The other investment-relevant lesson is something I have been emphasising for a while: differentiation is key. Spain’s economic performance has leaped ahead of Italy; this should continue to be reflected in their relative asset prices.

I believe Europe will remain divided for the next several years at least; more cross-country differentiation and a weaker bias to the euro are, in my view, the two key implications.

Get more perspectives from Franklin Templeton delivered to your inbox. Subscribe to the Beyond Bulls & Bears blog.

For timely investing tidbits, follow us on Twitter @FTI_Global and on LinkedIn.

*****

What Are the Risks?

All investments involve risk, including possible loss of principal. The value of investments can go down as well as up, and investors may not get back the full amount invested. Bond prices generally move in the opposite direction of interest rates. Thus, as prices of bonds in an investment portfolio adjust to a rise in interest rates, the value of the portfolio may decline. Investments in foreign securities involve special risks including currency fluctuations, economic instability and political developments.

Important Legal Information

This material is intended to be of general interest only and should not be construed as individual investment advice or a recommendation or solicitation to buy, sell or hold any security or to adopt any investment strategy. It does not constitute legal or tax advice.

The views expressed are those of the investment manager and the comments, opinions and analyses are rendered as of May 29, 2019, and may change without notice. The information provided in this material is not intended as a complete analysis of every material fact regarding any country, region or market.

Data from third party sources may have been used in the preparation of this material and Franklin Templeton Investments (“FTI”) has not independently verified, validated or audited such data. FTI accepts no liability whatsoever for any loss arising from use of this information and reliance upon the comments opinions and analyses in the material is at the sole discretion of the user.

______________________________________

1. The BBC notes that parties with an anti-Brexit stance, namely Lib Dems, Greens, SNP, Change UK and Plaid Cymru won a combined 40.4% of the vote vs. 34.9% by Brexit Party and UKIP. https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-politics-48403131

2. One of the convergence criteria set out in the 1992 Maastricht Treaty called for countries wishing to join the euro to have a government debt to GDP ratio less than 60%, or, if the ratio exceeded 60%, that it should have “sufficiently diminished and must be approaching the reference value at a satisfactory pace”.

Copyright © Franklin Templeton Investments