by Craig Basinger, Chris Kerlow, Derek Benedet, Alexander Tjiang, RichardsonGMP

The Canadian economy is forecast to expand by 2.1% in 2018 which is pretty much in the bag. However, in line with most global economies, ‘moderation’ seems to be the popular term for growth in the coming years with forecasts for 2019 sitting at 1.9% and 1.7% for 2020.

Beneath this headline number, which don’t sound so bad, there are a few contributors/detractors that may prove more troublesome. Before we jump into the negative signs, it’s important to understand that the Canadian economy would find it very difficult to fall into a recession with the U.S. economy doing well. The old adage “when the U.S. sneezes, Canada catches a cold” works both ways.

Canada has a hard time catching a cold when the U.S. is feeling healthy, which is the case today. In fact, the only time since 1960 that Canada suffered consecutive quarters of negative GDP growth with the U.S. economy still growing was the energy-induced slowdown in the 1H of 2015, which proved temporary on a national basis. Given U.S. economic growth is currently forecast at 2.5%, things south of the border are looking pretty good.

Canadian economic woes

There are certainly some headwinds for the Canadian economy. Insolvencies among Canadian companies rose 4.6% in Q3, the fastest quarterly increase in over five years. Now if these were concentrated in Alberta due to soft energy prices and infrastructure bottlenecks, we could blame this rise on industry centric factors.

However, this trend was evident across a number of provinces, some of which have no material energy exposure. With the consumer doing fine, our largest trading partner the U.S. still doing fine and the overall Canadian economy still expanding, the culprit appears to be higher interest rates.

Now, interest rates started moving higher in mid-2016 but remain low by historical standards. Too early to tell, but this could be evidence of just how sensitive our economy has become to changes in interest rates. Perhaps more sensitive than many currently already believe.

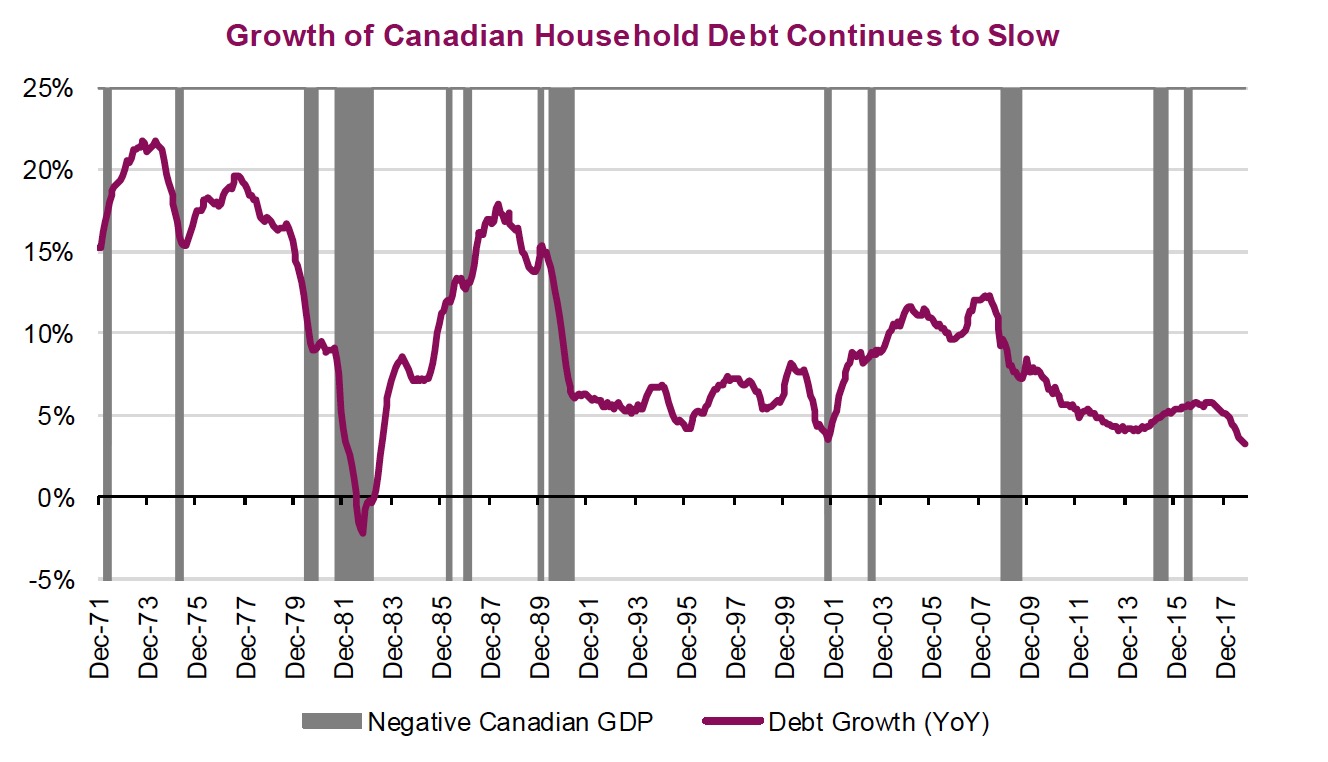

The Canadian consumer also appears to be feeling the pinch of higher yields. Canadian household debt reached a new record in November of over $2.15 trillion. Rising debt may sound negative but changes in debt actually correlate very strongly with economic activity.

It takes money to make money. So a new record high is a positive for the economy; however, the growth rate in total debt continues to slow, down to levels that have only been seen during recessions (chart on page 1). And this isn’t just attributable to the slowdown in home sales as consumer credit debt growth has been slowing along similar lines. [note we will be revisiting the housing industry in next week’s edition of Ethos].

Slow debt growth, the continued situation on the energy front, some softness in housing plus even faster moderating growth among developing economies (that tend to be source of marginal demand for resources) … it doesn’t paint a great picture for the home team.

And if our economy really has become ‘uber’ sensitive to interest rates, there may be another issue. Say the U.S. economy keeps performing well (our expectation), their yields will remain elevated. Even with a softer outlook for the Canadian economy, our yields will be dragged along for the ride. This would negatively impact the levered consumer and the interest rate sensitive housing industry.

But we have a plan

There is some good news. First, the economic headwinds for Canada may be largely evident in valuations. We have written in the past months about how much the price- to-earnings multiple (PE) for the U.S. has fallen in 2018. Well, the TSX PE has fallen from 17.5 to 13.5 over the past two and a half years.

With many companies trading so cheaply by historical standards, this clearly is reflecting to some degree the Canadian and developing economies moderation.

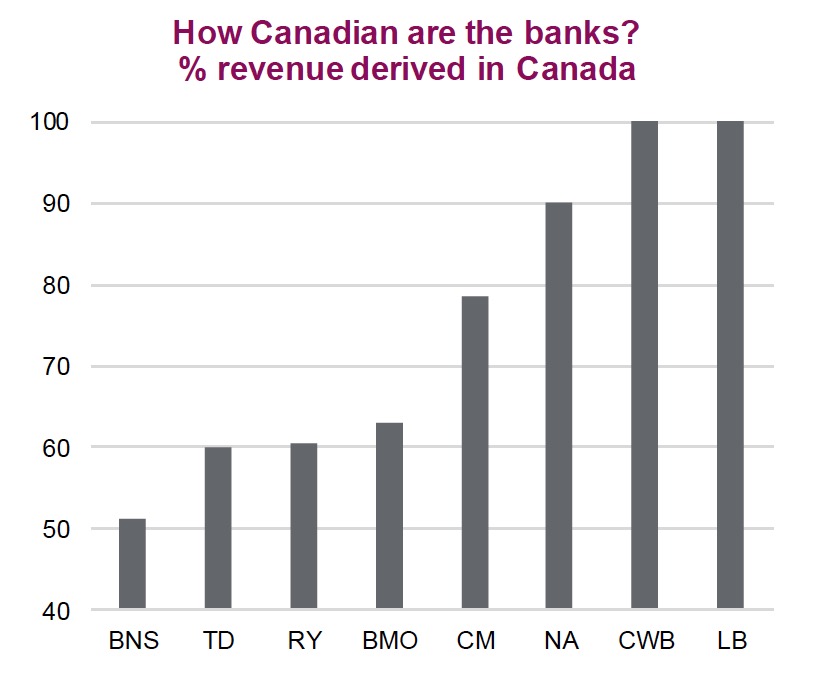

The other strategy that may benefit investors is once again focusing on Canadian companies that generate most their sales from outside Canada. Especially those with more U.S. exposure, you may be getting the benefit of a more robust U.S. economy at a Canadian discounted valuation. Sweet.

The top chart is a breakdown of domestic revenue by sector for TSX members. Industrials and Technology jump out as potential fitting this mold. The Industrial average is 45%; however, when you get to the company level there is a large range. Names like ATA, CAE, NFI, BBD, SNC are all much more global.

Financials tend to be more domestic focused but again, this varies substantially across names. BNS, TD and RY among the banks have the largest non-Canadian revenue. The life insurance companies tend to have an even lower exposure to Canadian revenue.

Certainly a factor worth considering with ‘moderation’ varying from one economy to another.

*****