by Niels Jensen, Absolute Return Partners LLP

Inflation is when you pay fifteen dollars for the ten-dollar haircut you used to get for five dollars when you had hair.

Sam Ewing

Have you bought The End of Indexing yet?

2½ years of hard work, day and night, has come to an end. The End of Indexing (my new book) is finally out and can be found in various book stores around the world or, alternatively, you can order it from Amazon or directly from the publisher (Harriman House).

I don’t often make promises in the Absolute Return Letter. My compliance manager tells me that the combination of providing investment advice and making promises is not a good one. Having said that, I will now make you a rare promise. I will guarantee that the better The End of Indexing sells, the less I will mention it going forward.

Having said that, I hope you’ll forgive me for having done a bit of marketing in the last few letters. I am no Warren Buffett, and I have to use the marketing channels at my disposal. So, if you haven’t yet bought the book, please give it some consideration (Exhibit 1).

Sources: Harriman House & True Design

The structural outlook for inflation

In last month’s Absolute Return Letter I discussed the cyclical outlook for inflation, and it wasn’t my intention to re-visit the topic only a month later, but sometimes things happen when you least expect it.

In this case, only a few weeks ago, I received a new research paper from Oxford Economics, which made it virtually impossible for me not to bring up the topic of inflation again. In a few minutes you’ll understand why, but let’s start somewhere else. Let’s begin by looking at how investors perceive the impact of ageing on inflation, because that’s not so straightforward.

The view from the blue corner

In the blue corner you’ll find the traditionalists; those who believe that ageing of society is disinflationary. That is very much the conventional opinion as to how ageing impacts inflation and appears to be driven by the lessons learned from Japan – a country that is years ahead of the rest of the world as far as the ageing process is concerned.

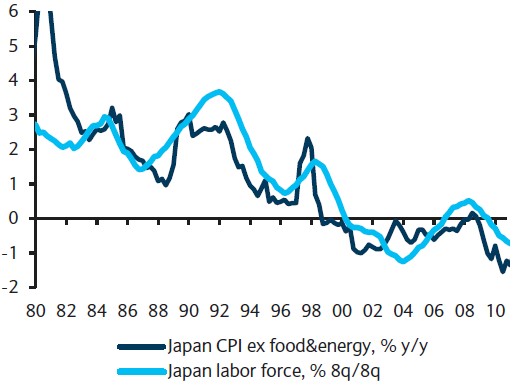

As Japanese consumers have aged, they have definitely consumed less, and that has had a meaningful disinflationary impact on the local economy (Exhibit 2). Today, the conventional view amongst demographic researchers is that ageing is at least disinflationary, and perhaps even deflationary.

Source: Barclays Equity Gilt Study 2014

The tight link between a shrinking workforce and falling consumer price inflation in Japan has even led some commentators to argue that it is only a question of time before Europe begin to walk down the same slippery slope – if that journey hasn’t already begun.

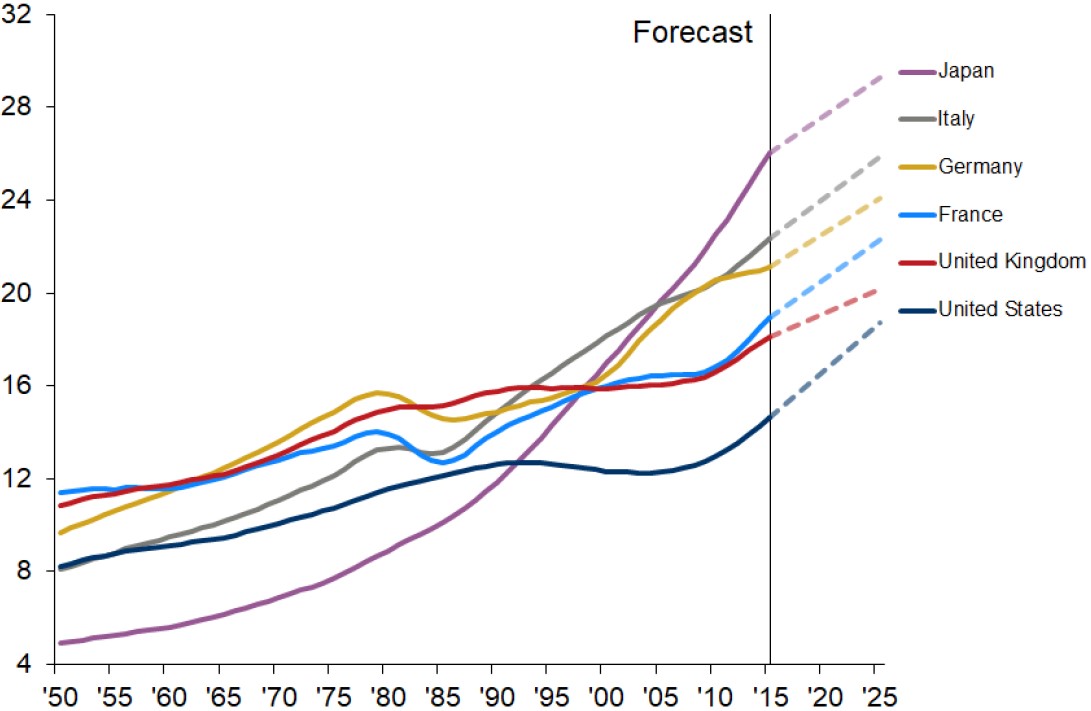

We are only a few years away from Italy and Germany having as many 65+ year olds as Japan have today (Exhibit 3) and, by the middle of the century, Italy will actually have more 80+ year olds than Japan (which you cannot see from Exhibit 3).

Source: Oxford Economics, United Nations, 2018

The view from the red corner

The views just expressed were very much how I looked at things until 2015. Then, in February of that year, my world turned upside down. The Bank for International Settlements (BIS) published Working Paper no. 485, containing the surprising conclusion that ageing is in fact (modestly) inflationary.

How come? Didn’t I just state that the older generations consume less than their younger peers do, leading to falling consumer demand as society ages? And, if consumer demand starts to drop, wouldn’t you expect consumer price inflation to drop as well, just like it did in Japan?

In their 2015 paper, the researchers at BIS argued that life is a tad more complicated than that, though. As people age, demand for consumer goods certainly drops, i.e. the demand curve shifts to the left but the supply curve shifts even more, as the ageing consumer no longer manufactures anything, once he has retired. In other words, BIS’ argument is a relative one rather than an absolute one.

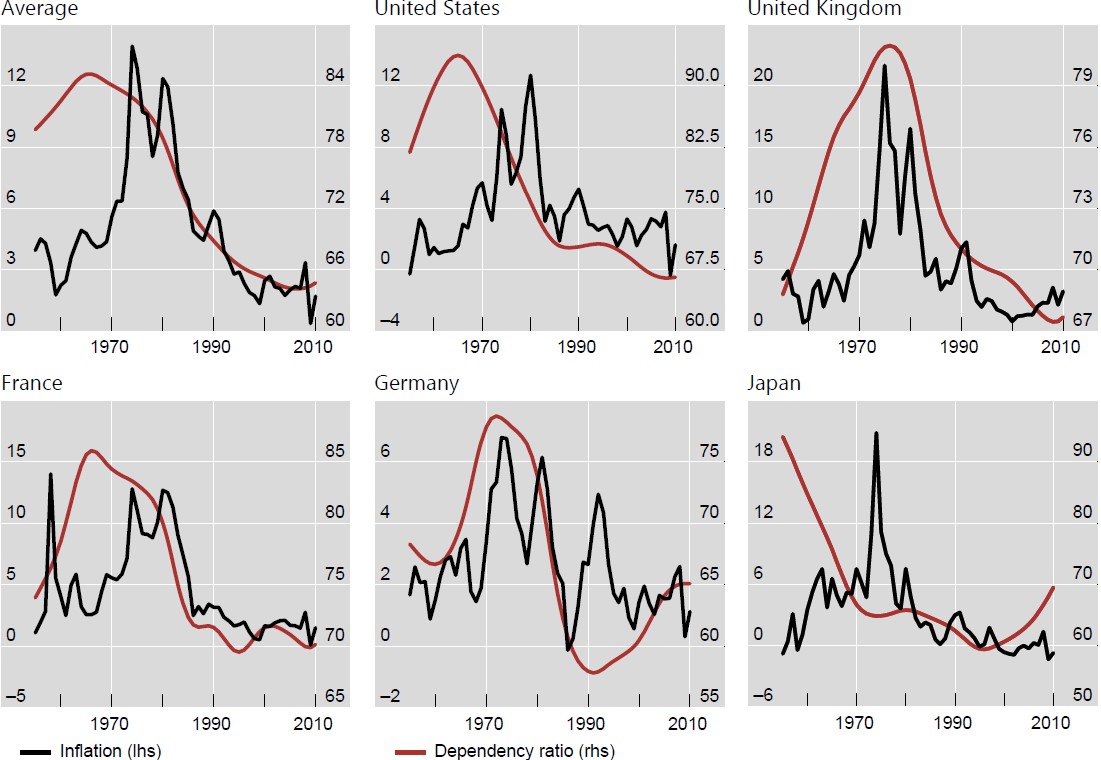

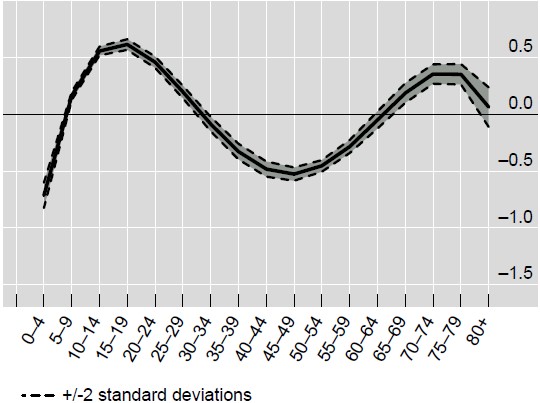

The BIS researchers found that, in most countries, inflation has moved more or less in tandem with the dependency ratio[1]; the more dependents, the higher the rate of inflation and vice versa (Exhibit 4). (Note: The dependency ratio is the number of dependents (those aged 0-14 and 65+) to the total working population (those aged 15-64)).

Source: BIS Working Paper no. 485, Bank for International Settlements, 2015

Critique of the BIS paper

Neither side is backed by an inordinate amount of research, though. There is a surprisingly modest amount available to those keen to dig deeper on the topic. Consequently, I have struggled to form a clear view myself but, as you shall see in a moment or two, I am closer to choosing sides than I have ever been before.

My first inclination was to blame it all on BIS’ choice of independent variable (the dependency ratio). By including the 0-14-year olds, I suspected that the final result was prejudiced. After all, don’t we all know that children are tremendously expensive? BIS looked at different age groups’ impact on inflation and, although children affect inflation more than the elderly do, BIS found the difference to be surprisingly small (Exhibit 5).

Source: BIS Working Paper no. 485, Bank for International Settlements, 2015

Secondly, the BIS study didn’t distinguish between different age groups in the 65+ category. In reality, it makes a massive difference how old the elderly are. People aged 70 spend a lot more money than those aged 85, and they spend it very differently. BIS didn’t address this issue at all

Thirdly, either economic or political factors can drive the demographic impact on inflation. BIS found in its research that, although both sets of factors have indeed impacted inflation over time, the effect from changing economic conditions is greater than that of political factors. This is important, as it makes BIS’ findings more robust.

Fourthly, take another look at Exhibit 4. The spike in inflation in the late 1970s and early 1980 not only coincided with a peak in the dependency ratio; it also coincided with the second oil crisis and the ensuing inflation calamity. Could it be that the apparent link between demographics and inflation is just a coincidence? That inflation is in reality driven by economic factors such as oil prices? BIS tested for this and found their results to be robust, but I believe that’s the Achilles’ heel of the BIS study. I am certainly not as confident as they are that the spike in inflation during that period wasn’t in fact driven by rising oil prices.

The new research

The issue has simmered in the back of my head ever since BIS published their paper back in 2015. On one hand, I have found it hard to take their arguments apart; on the other hand, Japan is living proof that ageing is anything but inflationary.

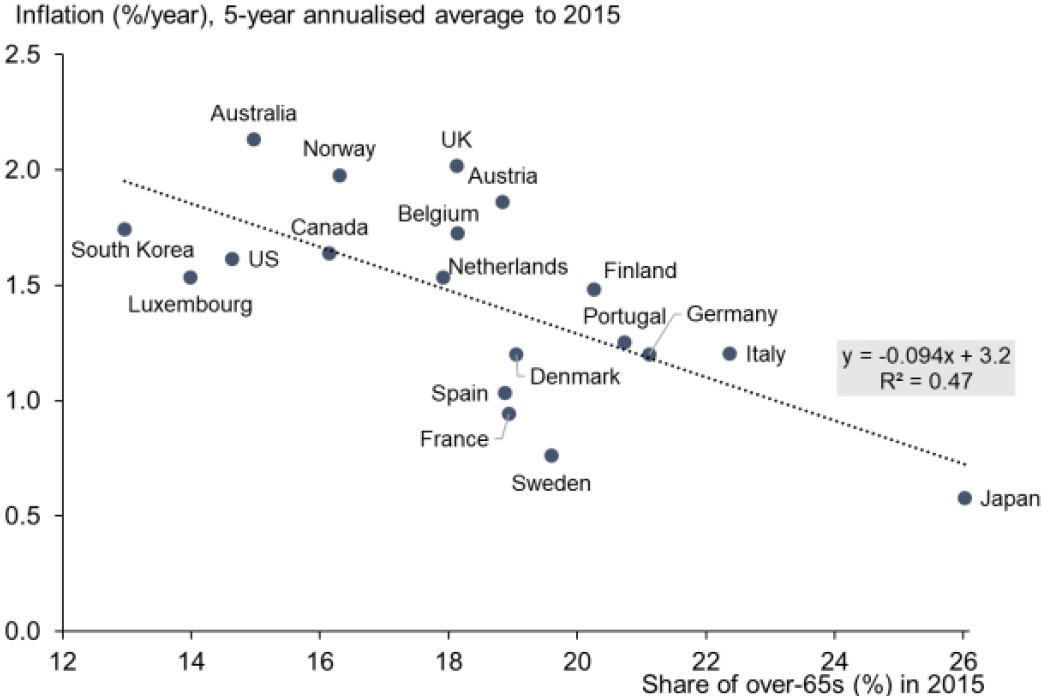

Then, in late February, a new research paper from Oxford Economics dumped through my letterbox, arriving at a very different conclusion than BIS arrived at in their 2015 paper, when they surprised the financial world by concluding that ageing is in fact inflationary. The researchers at Oxford Economics found that, at least more recently, the share of elderly (65+ years of age) in advanced economies is highly negatively correlated with consumer price inflation.

In the five years to 2015, an astonishing 47% of the cross-country variation in inflation rates can be explained by the number of 65-year olds and older when measured as a percentage of the overall population (Exhibit 6). In other words, according to Oxford Economics, ageing is very clearly disinflationary.

Source: Oxford Economics, United Nations, OECD, 2018

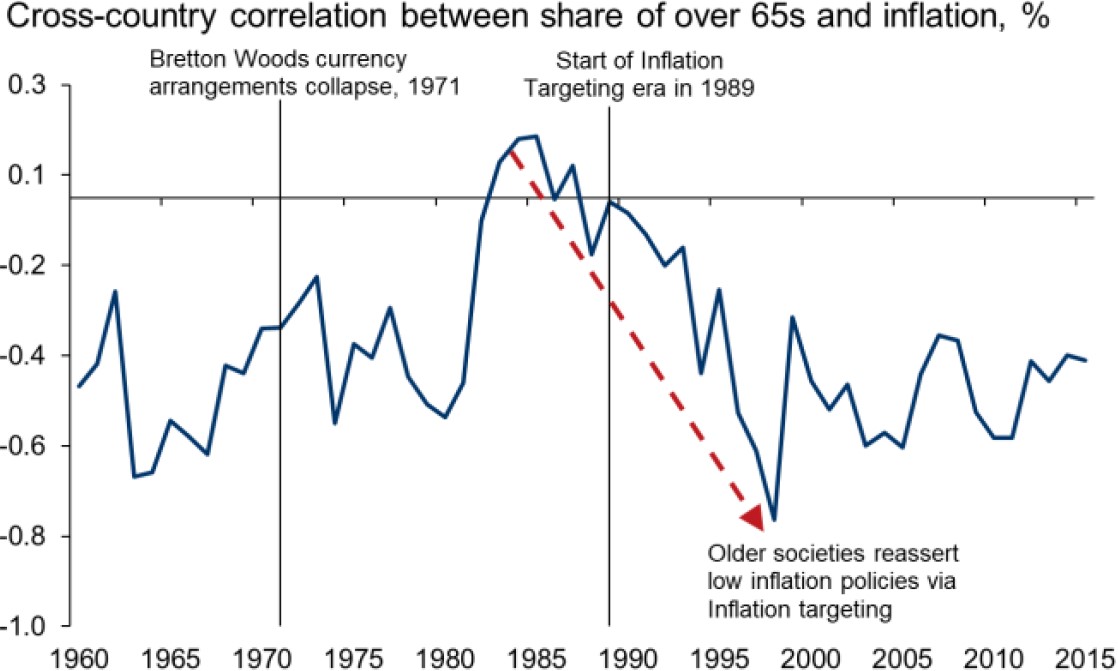

Oxford Economic also found that, in the last 60 years, apart from a brief spell in the 1980s, the cross-country correlation between consumer price inflation and the share of elderly has been consistently negative (Exhibit 7). As you can see, from the mid-1980s to the late 1990s, the correlation coefficient took a nosedive from about +0.2 to -0.7 and has only recovered modestly since, with the correlation coefficient hovering around -0.4 today.

Note 1: The solid line represents the correlation in each year based on 21 OECD economies.

Note 2: Excluding Japan makes little difference to the results.

Note 3: In 1989 New Zealand became the first economy to target inflation.

Source: Oxford Economics, United Nations, OECD, 2018

Before you start arguing that it is all due to Japan, and that the result would come out very differently if only you removed Japan from the sample, I can tell you that the researchers at Oxford Economics did precisely that, and it made little difference.

Comparing the two studies

When two studies that look at virtually the same underlying data arrive at such different conclusions, it is only fair to ask a few questions. My first instinct was to point to the different time series used in the two studies as the guilty party. BIS used data from 1955 to 2010, whereas Oxford Economics tuned in on the period 2011-2015.

For a while I managed to convince myself that the two studies came to such different conclusions, because they looked at different time periods; however, as you can see from Exhibit 7, the negative correlation is not exactly a new phenomenon, so my logic fell apart as soon as I started to dig deeper.

I then contacted the author of the Oxford Economics study (Gabriel Sterne) to get his opinion, and he delivered quite an interesting summary of his findings. (Note: … for which I am eternally grateful. The following few paragraphs are very much an extract of my conversation with him. Thank you, Gabriel.) Gabriel divides his reasoning into two parts – economic theory and empirics. On the theoretical side, in favour of the BIS study is the simple fact that old people don’t produce much (if anything at all), but they still consume, which should drive savings lower, and inflation as well as real interest rates higher.

Having said that, it didn’t take long for Gabriel to line up several arguments against the BIS findings. For example, he pointed to the fact that the younger generations are expected to live longer than their parents and therefore save more which, according to economic theory, should drive interest rates down. He also stressed that, as far as real interest rates are concerned, the stock of savings matters as much as the flow of savings, and that the elderly have (much) higher stocks than their younger peers do.

Other things equal, Gabriel therefore thinks economic theory comes down in favour of ageing leading to disinflation rather than inflation unless the elderly are suddenly saddled with exploding healthcare costs or their stock of savings prove insufficient to take them through retirement. One could actually argue that the BIS point-of-view, which favours an inflationary outcome, applies more to the 1950-1990s than it does to the current environment (see my concluding remarks as to why that is).

The big methodological difference between the two studies is that BIS take a time series approach, whereas Oxford Economics look for differences between countries at a given point in time. Also, by ending their study in 2010, even when the research paper wasn’t published until 2015, one could argue that BIS have blatantly chosen to ignore the period of the most dramatic demographic changes (i.e. recent years). In that context, I note that the explanatory power of BIS’s regressions drops somewhat post-1995 (they admit as much themselves).

Concluding remarks

Instead of totally disregarding BIS’ study, I would argue that, whilst there is plenty of evidence that ageing was (modestly) inflationary through the mid-1990s, several structural changes more recently have reversed that trend, so that ageing of society is now disinflationary.

Globalisation, i.e. the ability to import the goods and services the elderly need but no longer produce, and higher stocks of savings amongst the elderly after 35 years of an extraordinary bull market in both bonds and equities, are only two examples why today’s environment is quite different from yesteryear’s – why the inflationary impact of ageing may have changed in recent years.

That is particularly relevant in the context of last month’s Absolute Return Letter, where I argued in favour of a short-term spike in inflation driven by cyclical factors. I am not suddenly walking away from that viewpoint, as I continue to believe that we could be in for a nasty surprise or two, as the year unfolds.

That said, central bankers weren’t born yesterday. They are often prepared to look beyond the near term, if they see a different picture unfolding longer term, and this could very well be one of those situations. If that were to happen, central bankers would indeed be heavily criticized for falling behind the curve, but I strongly suspect they know precisely what they are doing.

The more cynical side of me would even suggest that today’s central bankers probably wouldn’t mind falling behind the curve for a while. The world is so indebted now that something rather drastic needs to happen. And, if central bankers are confident that inflation will indeed cool off again longer term, couldn’t we do with a healthy dose of debt destruction? That is precisely what a bout of inflation would result in.

Copyright © Absolute Return Partners LLP