by John Lynch, CIO, & Team, Comerica Wealth Management

It was a little over 15 years ago that in response to the Great Financial Crisis (GFC), investors around the world were convinced of the concept of negative interest rates. Yes, we were told that for the global economy and financial markets to recover, borrowers would be paid, and savers would be charged. Indeed, desperate times required desperate measures and negative interest rates were among the many emergency measures undertaken by global fiscal and monetary authorities. While the Federal Reserve exhibited a modicum of restraint with its zero-interest rate policy (ZIRP), market interest rates around the world were artificially suppressed for over a decade, providing mixed economic benefits with significant tailwinds for risk assets. See Chart: Global Market Value of Negative Yielding Debt

At its peak, the value of negative yielding debt around the world exceeded $18.3 trillion in December of 2020. For all the monetarist concerns that inflation would result, it wasn’t until the global pandemic that significant pricing pressures developed, prompting global central bankers to “think about thinking about” raising interest rates. Yet it wasn’t until two years later that the Federal Reserve and the ECB responded with significantly tighter monetary policy, increasing rates to pre-GFC highs. The export-driven Japanese economy, however, persisted with extraordinary measures until yen weakness persisted to the point it was no longer beneficial.

Diverging Central Bank Policies

While developed market central banks have reached an inflection point, the direction of interest rates differs in some of the world’s largest economies. This could lead to further challenges as policy prescriptions weigh on global economies and financial markets.

Federal Reserve

The big question leading up to last week’s FOMC meeting was whether policymakers would trim their projection for three interest rate cuts in 2024 following higher than expected inflation data. The answer was a resounding “no.” The Fed’s policy statement was virtually unchanged from the prior meeting and the outlook remains at 75 basis points of cuts for the year. Most importantly, Fed Chair Jerome Powell didn’t dismiss the notion of cutting rates as early as May or June. Markets cheered the news sending the major domestic equity indexes to fresh all-time highs, while yields retreated and the dollar sank.

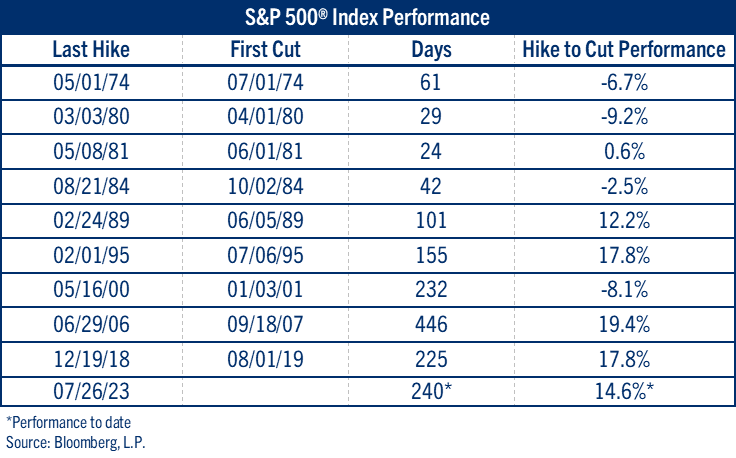

The market’s reaction to what appears to be an imminent cut by the Fed follows historical precedent. Fed pauses, the periods between the last hike and the first cut, are usually marked by solid returns for equity investors. It stands to reason that risk assets rally as rate cuts come into view. Interestingly, longer pauses have generated better returns. In four of the five previous pauses that were longer than 100 days, the S&P 500® has generated double-digit returns. See Chart: S&P 500® Index Performance

While the Fed has maintained its interest rate projection for this year, there have been notable adjustments to other forecasts. The year-end inflation projection, measured by Core PCE, has been revised upward to 2.6% (vs. 2.4% prior). GDP forecasts for this year have also been increased to 2.1% (vs. 1.4% prior) with additional upward movement in future years. Finally, longer-term interest rate forecasts were also pushed higher. Rates for 2025 were increased to 3.9% (vs. 3.6% prior), and 2026 rose to 3.1% (vs. 2.9% prior).

The bottom line is that the Fed seems comfortable with allowing inflation to run hotter than previously expected this year, aiming to bring it back to the 2.0% target through a more gradual series of rate cuts next year and beyond. Just remember that when the Fed typically cuts rates, it does so because it has to, with the associated near-term risks of economic and market volatility.

Eurozone Central Banks

The Fed was not the only central bank to signal that concerns over inflation are fading.

The Swiss National Bank announced a surprise cut last week, becoming the first major economic power to do so. Inflation has also been slowing considerably in the U.K., where the Bank of England announced they would keep rates steady but saw several policy hawks ease their stance. Futures markets are pricing in cuts to commence between June and August. European Central Bank (ECB) President Christine Lagarde reiterated plans for a possible cut in June.

Bank of Japan

The Bank of Japan (BOJ) ushered in a new era of Japanese monetary policy last week, cancelling negative interest rates and yield-curve control. The move marked the first increase in rates by the BOJ since 2007 and brought the Japanese benchmark rate into positive territory for the first time since 2016.

Japan has long been considered the outlier amongst central banks. While much of the world was facing inflationary pressures, Japan has been concerned with too little inflation. The policy shift marks a significant step towards policy normalization. Nevertheless, real interest rates, after accounting for inflation, remain deeply negative in Japan—more so than any other major economy.

Conclusion - Possible Ramifications

In a typical environment, a normalization of rates should lead to an improved allocation of capital around the world, as proper risk taking is rewarded. Borrowers can be charged market-based lending fees and savers can benefit from their prudence.

Yet decades of ultracheap money have led to a massive misallocation of capital, with unprofitable companies surviving simply through financial engineering. In addition, sovereign debt markets have been altered, as they carry trade enabled investors to borrow cheap currencies like the yen at low rates and invest in other markets. As the BOJ moves towards normalizing its monetary policy, an unwinding of these trades could have significant implications for global financial markets, particularly the $27 trillion U.S. Treasury market.

Should global central banks reduce their appetite for U.S. government debt, the support mechanism of the past decade becomes increasingly frail, particularly if inflation persists. Longer-term interest rates may then face upward pressures, weighing on economic and market activity, despite the Fed’s intention to lower its target for the Federal Funds rate.

Be well and stay safe!

Contributors

John Lynch

Chief Investment Officer

Comerica Wealth Management

Deborah Koplik

Director Portfolio Management

Comerica Wealth Management

Matthew Anderson

Senior Analyst

Comerica Wealth Management

Copyright © Comerica Wealth Management