by Ryan James Boyle, and Vaibhav Tandon, Senior Economists, Northern Trust

Populations are aging, and the economic consequences will be substantial.

"Demography, not democracy, will be the most critical factor for security and growth in the 21st century", said Lee Kuan Yew, Singapore’s founding father. While democracy remains a key pillar for peace and prosperity, his emphasis on the value of human capital wasn’t misplaced. The scale and ability of the labor force are important foundations for long-term economic progress.

Globally, demographic risks were evident well before the pandemic. Then, COVID-19 took a steep toll on the labor force and altered broader demographic dynamics. From fertility to life expectancy to mortality to migration, demographic challenges have only compounded.

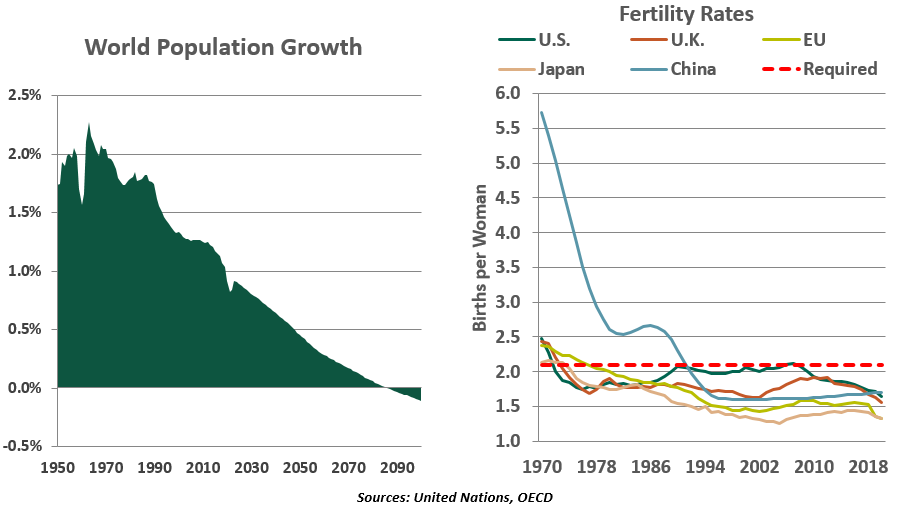

The world’s population continues to grow, but the pace of growth has slowed to a rate of under one percent, a pace not seen since 1950. The populations of 61 nations are projected to decrease by 1% or more between now and 2050.

Global fertility rates have been in secular decline for years. Prosperity is a key contributor: over time and across geography, countries that get wealthier have fewer children. (The opportunity cost for parents missing work to raise families is higher in those cases.) Periods of economic uncertainty tend to depress fertility: evidence from the 2008 financial crisis supports this thesis. In this respect, the COVID downturn was typical; early evidence suggests births fell in the pandemic.

And at the other end of our life cycles, COVID-19 also had a tremendous impact. Excess mortality increased even further in 2021, while life expectancy decreased in many countries. Global life expectancy at birth fell to 71.0 years from 72.8 in the two years of the pandemic. The elderly remain at greatest ongoing risk of succumbing to COVID-19. Many survivors have been dealing with the limitations of "long COVID."

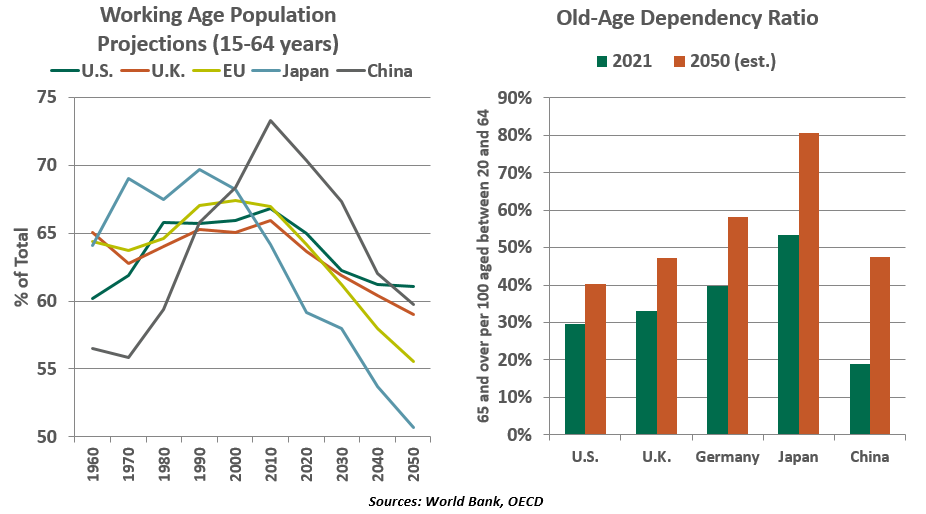

Most developed economies have been graying, thanks to low birth rates and rising life expectancy. As a result, the labor force as a proportion of the total population has been on a long-running decline. COVID impaired the labor force even further. Older workers in the U.S retired somewhat earlier than expected, and haven’t returned to the labor force.

Aging In Place

The share of the global population aged 65 years or above is projected to rise from 10% this year to 16% in 2050. The cohorts who are younger are much smaller, meaning fewer workers are supporting a larger retired population. Emerging markets like China, India, and Brazil that have been reaping benefits of a demographic dividend will soon see a dramatic reversal.

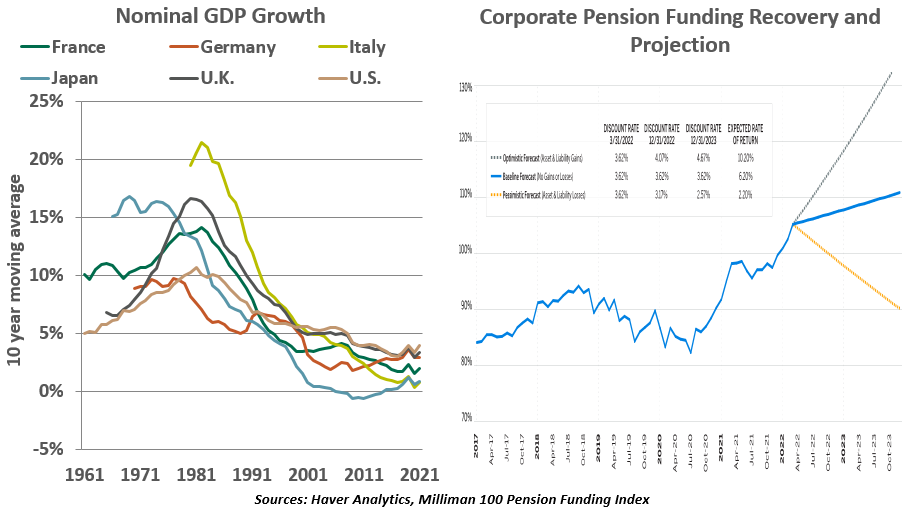

The retirement of the post-war Baby Boom generation is partly responsible for the slower growth in developed nations. A 1% fall in the supply of labor results in a similar 1% reduction in of gross domestic product. The ongoing wave of retirements is an unsettling prospect for the world economy, considering the demographic trends today in the U.S., Europe and China.

Birth rates in Asia, already very low, fell even further during the pandemic. China’s demography is particularly worrisome; the formal end of the one-child policy about seven years ago hasn’t boosted birth rates, a worrying trend for a rapidly graying nation. The share of those aged 60 years or above is set to climb from 19% of the total population (over 260 million) today to one-third of the population before 2050. Combined, these factors mean the world’s most populous country is expected to experience an absolute decline in its population as soon as 2023.

Demographic shifts are a central economic issue for the next generation.

China’s social security system is the largest network in the world, but it’ll have to do more to deal with the ensuing social changes. China’s labor-intensive manufacturing has been a cornerstone of economic success, but the drive to invest in robotics threatens to cause large-scale unemployment in the industrial sector. Displacement of workers will push them into national benefit plans, which are less generous than those provided by employers. As a middle-income economy, the country may gray before it becomes a high-income economy. Fewer people also mean less domestic consumption, and thus rapidly slowing economic growth as its export-led opportunities have peaked.

The implications of an aging society are vast and varied. An increasing old-age dependency ratio and shrinking share of working-age population leads to changes in patterns of saving and investment, shortages in labor supply and a possible decline in productivity. Retirement obligations will escalate significantly in the years ahead, putting strain on welfare systems and government finances. In the end, all of this reduces economic growth.

National saving is not only a source of investment, but is also vital to the demand for financial and real assets. Aging societies both save less (as retirees draw down savings) and spend less, which lowers capital formation. An environment where businesses are discouraged from investing can lead to secular stagnation, a condition characterized by negligible growth and low real interest rates. Japan’s economy illustrates this risk.

Aging populations will strain our welfare systems and government finances.

Productivity in the developed world had been growing slowly. The pandemic could prove to be the medicine needed to boost efficiency led by increased digitalization and greater adoption of technology. Repetitive components of jobs will be taken over by automation and artificial intelligence. That said, as factories and processes become more automated, workers will have to be reskilled. Productivity tends to decline with the age of workers, who are unable or unwilling to adapt to new technology.

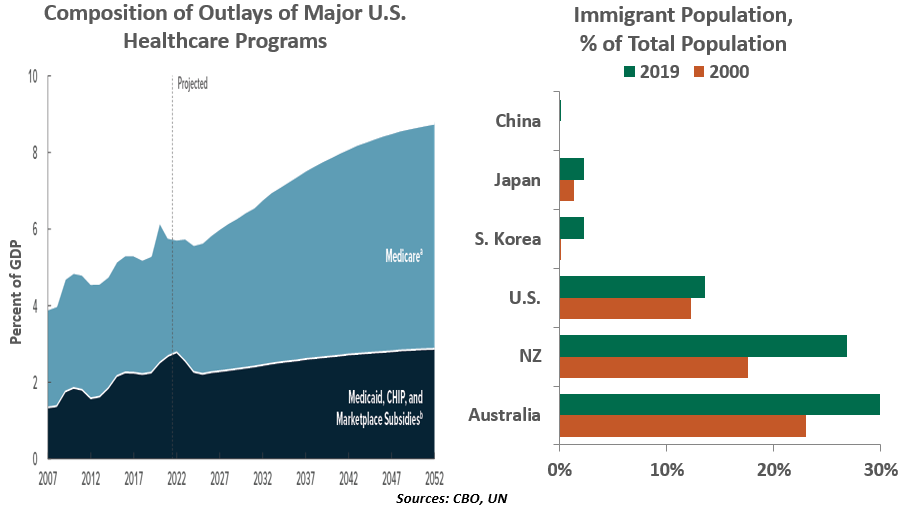

Longer life expectancy is a mixed blessing. Life itself is priceless. However, adding to our senior years will require more spending on healthcare. Greater public expenditures will strain public coffers, while greater private spending will deplete retirement savings and reduce inheritable wealth.

A robust pension system might not be the answer to demographic woes, but can help create a peaceful and prosperous economy. Though shortfalls in global retirement systems were soaring, rising interest rates have helped close the gap by lowering discount rates of pension funds. An increase of one percentage point in interest rates reduces average pension liabilities by 12-15%. U.S. corporate pension discount rates are up 180 basis points in the first half of the year, which reduced pension liabilities by about 20%. When pension liabilities decline, the impact is positive on their funded status.

Any Relief In Sight?

The challenge of demographics has no easy answers. Working longer is part of the solution, but workers have their limits. How can an aging populace get younger? As the fountain of youth continues to prove elusive, we are left with two avenues: More births, and more immigration.

A population that averages fewer than 2.1 births per woman is likely to decline, and most advanced economies have fallen below that rate. Government policy can do little to support fertility. Financial considerations are substantial when planning a family: a recent study estimated a cost to U.S. parents of over $300,000 per child.

Government programs can defray some of these costs through public childcare, tax credits and direct financial support, but a baby is not merely a major purchase. Fiscal supports are an afterthought relative to the life-changing commitment of child-rearing. We find it instructive that nations that offer the most generous support to young families have seen no uptick to their birth rates. And even if family support policies could be highly effective, increased births today will take decades to grow the working-age population.

Migration waves should be part of policy plans going forward.

Advanced economies have a safety valve to address this gap: Welcoming more immigrants. Newcomers have a lot to offer demographically-challenged nations: They are generally younger, will work in difficult or dangerous jobs, are more likely to start new businesses and have more children. Successful western nations have a long tradition of welcoming immigrants and maintaining a reputation for being a place where ambitious migrants can improve their lives.

But suspicion of immigrants is long-standing. Political will to facilitate immigration is often limited, which can spur undocumented border crossings. A well-structured immigration policy is not zero-sum and will not exclude opportunities for the native population. The persistently high level of job openings and turnover, especially among lower-paid workers, suggests that the tight labor market would benefit from a greater supply of labor.

Whatever one’s feelings about migration, we should brace ourselves for more of it. Political risk has led to recent surges of migration to Europe, including those fleeing the Arab Spring uprisings and the invasion of Ukraine. Even if geopolitics calms down, climate risk is poised to create more climate refugees fleeing areas that become unlivable amid rising temperatures and higher sea levels. Already, we see the risks of massive flooding displacing populations as well as relocation to escape areas prone to wildfires, a trend shared across developed and emerging markets alike.

Nations that successfully welcome migrants will need to give thought to sustainable development. The growth of the population itself may not be the direct cause of environmental damage, but could exacerbate the problem. Climate refugees flowing into regions with limited fresh water or at increased risk of flooding will not find any refuge at all.

As we shape our outlooks for both our publications and our lives, demographics are a factor we cannot ignore. How will aging populations affect our lives?

- Higher taxes. Rising pension and healthcare obligations will require more and more government expenditure. The latest 30-year outlook from the U.S. Congressional Budget Office shows U.S. debt approaching double the level of the nation’s gross domestic product. Some increase in tax revenue seems unavoidable, and these higher outlays will crowd out other opportunities for government investment. A reduction in benefits may be part of the solution, but any such proposal will be politically challenging.

Aging populations bring the risk of limiting future economic growth.

- Working longer. The notion of retirement may become an anachronism. While some physically demanding jobs may keep a maximum age, workers should expect to stay in the labor force for longer. The pandemic’s normalization of remote work may create opportunities for more older workers to stay engaged and productive.

- More business investment. As prime-age workers become more scarce, employers will need to make more investments into productivity-enhancing, labor-replacing technologies. Automation still has a great deal of potential.

- Slower growth. Ultimately, an economy’s potential output is simply the product of its capital stock, labor force and labor efficiency. A smaller prime-age population will weigh on potential. In practice, this will mean more of the scarcity and disruption that COVID-19 previewed: logistics disruptions, staffing difficulties and reductions in business hours and service may become unfortunate parts of the new normal.

There is no escape from the persistent challenge of aging, individually and across broader populations. But the consequences of it can be managed and mitigated. The decisions that policymakers take today will determine the vitality of the world’s economy in the decades ahead.

Information is not intended to be and should not be construed as an offer, solicitation or recommendation with respect to any transaction and should not be treated as legal advice, investment advice or tax advice. Under no circumstances should you rely upon this information as a substitute for obtaining specific legal or tax advice from your own professional legal or tax advisors. Information is subject to change based on market or other conditions and is not intended to influence your investment decisions.

© 2022 Northern Trust Corporation. Head Office: 50 South La Salle Street, Chicago, Illinois 60603 U.S.A. Incorporated with limited liability in the U.S. Products and services provided by subsidiaries of Northern Trust Corporation may vary in different markets and are offered in accordance with local regulation. For legal and regulatory information about individual market offices, visit northerntrust.com/terms-and-conditions.