The path toward building reliable climate disclosures and stress tests will be a long one.

by Ryan James Boyle, Northern Trust

My children each had a phase of fearing visits to the pediatrician’s office, which often included vaccine shots. Their nerves led to tense and sometimes noisy moments in the examination room, even before any needles were visible. But initial discomfort was necessary to building long-term immunity.

A similar sense of nervousness is gripping corporate conference rooms as climate regulations start to take shape. The rules may come with new costs, but they will help to build immunity against a mounting category of risks.

The scope of climate regulation is growing far beyond polluting sectors. Power plants, manufacturers and land developers are no strangers to regulation: Broad environmental laws date to at least to the founding of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency in 1970.

In the present day, the Federal Reserve is on track to add climate risk to its regulatory expectations for banks. Last year, the Fed signed on to the Network for Greening the Financial System, a coalition of central banks developing climate policy for the financial sector. As we discussed at the time, while banks do not emit much carbon themselves, they have a fiduciary responsibility to assess their exposure to climate risk.

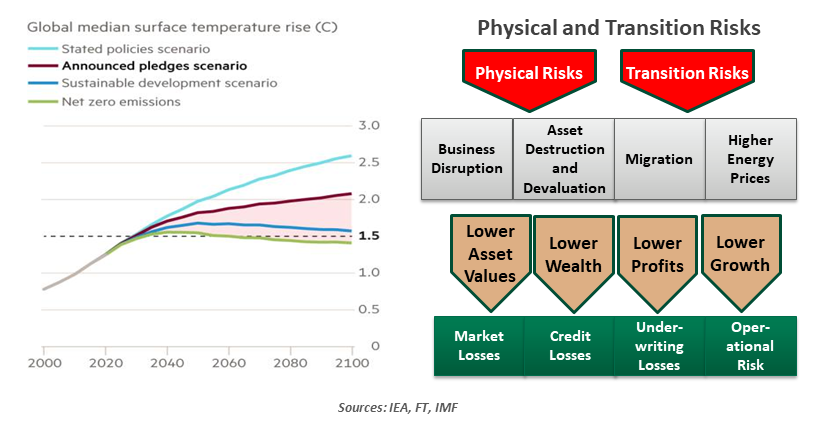

Last week, the regulatory outlook became clearer as Governor Lael Brainard gave a speech outlining the Fed’s thinking on climate scenario analysis. These tests will require banks to estimate their losses from the risks of climate change, including physical risks like severe weather events and transition risks encountered as the economy adapts.

Brainard related these nascent days of climate testing to the past challenge of designing capital stress tests for the financial sector following the 2008 Financial Crisis. The Fed’s early tests look simple in hindsight, but over time, the Fed’s requirements became clearer, the tests’ scope grew, and banks’ ability to model risks improved significantly. Brainard suggested an iterative approach, that the “rudimentary first attempt” at climate stress tests will lead to “subsequent improvements in modeling, data and financial disclosures.”

Brainard mentioned a specific requirement to differentiate test results by region and sector. Unlike recessions that can be assumed to include the same degree of stress for all parts of the economy, climate scenarios will have differing outcomes. For example, coastal cities are at greater risk from rising ocean levels, and hotter climates will suffer more from higher temperatures.

Banks have their work cut out for them. Climate scenarios are fundamentally different from stress cases that look like past recessions. Economic downturns follow a pattern: a shock, a contraction, and a recovery that play out in the span of a few years. Even pandemics had precedents. Climate scenarios, however, may have slower and more enduring outcomes than past economic cycles.

There is a high degree of coordination among financial regulators on climate risk. Brainard said the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) will set the standards for “consistent, comparable, and ultimately mandatory disclosures.” The Fed is not tackling this challenge alone, and by involving the SEC, requirements will not be limited to just Fed-regulated banks.

The SEC is already at work. The agency sets requirements for public company disclosures, including discussions of material risks to the company. Disclosures of environmental risks are long-standing, and the SEC published guidance for climate risks in 2010. In September of this year, the agency followed up with a sample letter demonstrating the details that they would expect to see in a climate disclosure. For instance, businesses will be expected to publish at least as much detail in their financial statements as is shown in their corporate sustainability report.

Banks are being asked to anticipate how climate change will impact their operations and their portfolios.

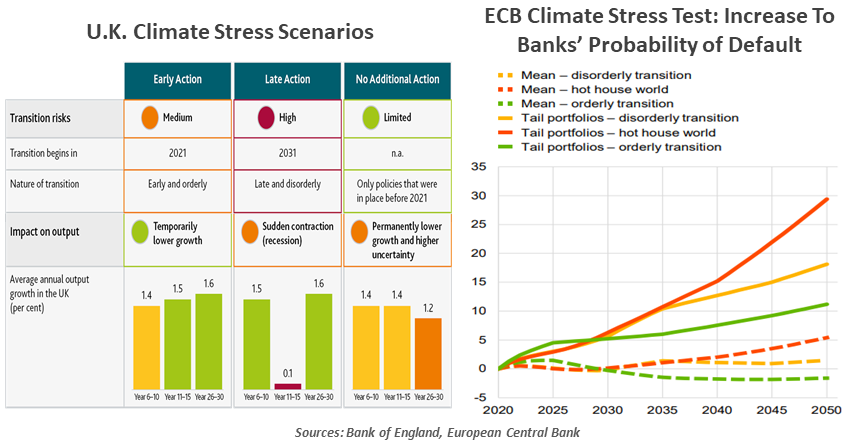

American regulators are playing catch-up to climate risk programs already in place elsewhere in the world. This year, the Bank of England launched its set of three climate stress scenarios for British banks, with results to be shared next year. The European Central Bank has also published the results of its first long-range climate stress test, estimating that loan defaults could increase up to 30% over the next 30 years in energy-intensive sectors if no climate mitigation takes place.

These regulators are building on efforts of voluntary coalitions. The CDP (formerly known as the Carbon Disclosure Project) has asked companies to voluntarily report their climate risk exposures for 20 years, enabling a scoring and comparison of each entity’s ability to manage this risk. The United Nations sponsors a Task Force on Climate Disclosures to harmonize global disclosures. These organizations lack a regulator’s enforcement capacity, but climate-sensitive investors are beginning to expect progress in these areas.

Most initial efforts appear to be focused on exploration and disclosure, encouraging or requiring companies to report on their exposure to climate risk. Actual stress testing is a higher hurdle. Earlier in September, researchers at the New York Fed offered an example of how a climate stress test could be performed on banks, by assessing each bank’s sensitivity and loan exposure to the oil and gas sector. While that approach alone is not a complete stress test, it could be a building block in a more comprehensive risk assessment.

Like other forms of stress testing, climate tests will yield useful insights.

The journey toward building reliable climate disclosures and stress tests will be a long one, with much effort expended along the way. But it need not solely be a drag on banks. Following a myriad of disruptions from fires, floods, and other climate-related incidents, stress tests can serve as a guide to more resilient operations. And an examination of transition risks can reveal potential opportunities to restructure portfolios.

In our family, we practiced resiliency by substituting the pharmacy for the pediatrician’s office as our preferred destination for shots. The procedure was no different, but the kids could focus on the rewards awaiting them in the candy aisle on the way out. It will take time and maybe some discomfort, but banks that prepare themselves for climate risk will be well-rewarded.

Don’t miss our latest insights:

Testing Times For Multilateralism

The Fed’s Ethics Are Being Tested

Information is not intended to be and should not be construed as an offer, solicitation or recommendation with respect to any transaction and should not be treated as legal advice, investment advice or tax advice. Under no circumstances should you rely upon this information as a substitute for obtaining specific legal or tax advice from your own professional legal or tax advisors. Information is subject to change based on market or other conditions and is not intended to influence your investment decisions.

© 2021 Northern Trust Corporation. Head Office: 50 South La Salle Street, Chicago, Illinois 60603 U.S.A. Incorporated with limited liability in the U.S. Products and services provided by subsidiaries of Northern Trust Corporation may vary in different markets and are offered in accordance with local regulation. For legal and regulatory information about individual market offices, visit northerntrust.com/terms-and-conditions.

Ryan James Boyle

Ryan James Boyle

Vice President, Senior Economist

Ryan James Boyle is a Vice President and Senior Economist within the Global Risk Management division of Northern Trust. In this role, Ryan is responsible for briefing clients and partners on the economy and business conditions, supporting internal stress testing and capital allocation processes, and publishing economic commentaries.