by Mo Ji, Chief Economist, China, AllianceBernstein

China is further along the coronavirus curve than much of the rest of the world and is on a fast path toward normal. We think its experience bears close watching—not only because China is a major contributor to global economic activity, but also because there will likely be important takeaways for the rest of the world as other countries plan their own reopenings.

In its first contraction since 1992, China’s GDP shrank 6.8% in the first quarter of 2020 as the country shut down in response to the novel coronavirus. But today, less than six months after its first identified case of COVID-19, China is getting back to work. Business is resuming. School bells are ringing. Construction workers are breaking ground.

It’s all made possible by the controls that China has put in place to allow gradual reopening during the pandemic.

China Flattens the Coronavirus Curve

In our view, China was able to flatten the curve quickly because of five governmental responses:

-

- Requiring facemasks since the start of the crisis. This is a must for resuming business.

-

- Strictly restricting imported cases in order to mitigate a second wave. Foreign visa holders are banned, and a 14-day quarantine is required after traveling overseas.

-

- Employing a combination of Western and traditional Chinese medicine to target a higher cure rate.

-

- Efficiently tracing and identifying cases using pay systems such as WeChat Pay and Alipay, as well as through geolocators on mobile devices.

-

- Adopting color-coded health QR codes. Red represents a confirmed case with travel ban. Yellow indicates a history of contact with a confirmed case or cases. And green signals the carrier is free to travel domestically.

While some of these measures bear costs—such as privacy—that other countries may choose not to incur, they have allowed China greater control over the spread of the disease and the route to economic recovery.

Measuring Progress in China’s Reopening

That route to recovery is taking less time than most observers anticipated.

For example, according to China’s Ministry of Education, 108 million (mostly secondary school) students were back at school on May 11. That’s 39% of the nation’s total. While some major universities are likely to remain closed for a while, we expect nearly 60% of China’s students to have returned to school by the end of the month.

Overall consumption has also ramped up quickly and is now up to 70% of last year’s levels. Even hotel occupancy is back to 50% of the prior year.

Indeed, the rebound in some sectors is so fast that it’s measured in the triple digits. Sales of heavy trucks, for example, rose 43% year over year in April; on a month-over-month basis, April sales increased 50% over March sales, and March sales increased 190% over February’s. Excavator sales—a proxy for construction activities—rose 60% year over year in April. These figures reflect strong rebounds in infrastructure and construction.

Even sales of autos, which had been in decline since mid-2018, saw growth in April. In part, higher sales reflect consumers’ change in behavior as they avoid public transportation during the pandemic.

In Tier 1 cities such as Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou and Shenzhen, a lottery system typically limits access to car license plates, but the Chinese government has recently relaxed these rules in response to return-to-work demands. In the biggest cities, whose streets were empty in February, morning rush hour is already coming early. By 7 a.m., Beijing and Shenzhen are experiencing major traffic jams as China returns to onsite work.

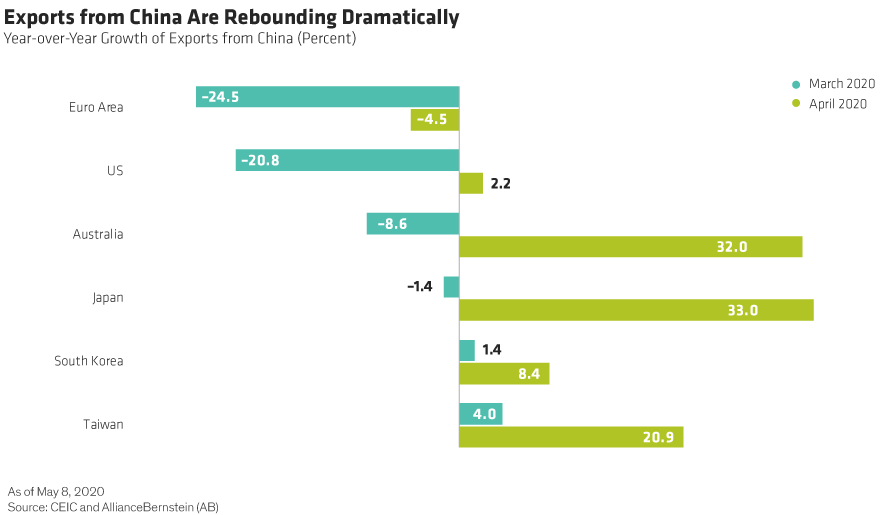

Thanks to external demand for medical supplies, precautionary stocking and catch-up orders, China’s April exports surprised to the upside, with growth at 3.5% year over year. That was a dramatic improvement over March export figures, at ¬–6.6%, and even the March data had shown more resilience than the market expected.

A breakdown of China’s exports by destination paints a picture of the drama unfolding in other countries as they too grapple with the sudden shuttering of their economies (Display).

Of course, not all data is on track to normal yet. In contrast to the favorable export picture, China’s imports were significantly worse than expected in April, at –14.2% year-over-year (versus ¬–0.9% in March), reflecting weaker domestic demand. But tellingly, while imports of crude oil were down modestly, imports of both iron ore and copper rose more than 20% in April as manufacturing came back online.

Renewed Risk of US–China Trade War

While China can control many factors at play, its expansive rulemaking has limits. For one thing, the likelihood of a potential US–China trade war is rising again as rhetoric heats up around the origin of COVID-19.

Though negotiators pledged to “create favorable conditions” for implementation of the Phase I trade deal, President Trump recently threatened to scrap the deal unless China meets its commitments. Disruptions to global cargo transportation due to the pandemic make meeting those commitments impossible.

Both the US and China have much to lose if negotiations unravel and the countries hike tariffs, particularly with economies in crisis and the US election around the corner. Ultimately, collaboration between the two countries is necessary for a resilient world economy and global markets.

We think it’s unlikely, therefore, that President Trump will withdraw from the Phase I deal. Instead, we expect more tough talk along the bumpy road between Phase I and Phase II. In these conditions, the exchange rate between the US dollar and the Chinese yuan will likely fluctuate between 7.0 and 7.1. An elevation in tariffs would trigger a depreciation to 7.2 or even 7.5.

China Faces Additional Unknowns

Of course, a potential trade war isn’t the only continuing uncertainty China must deal with.

There are questions about COVID-19 itself—how the virus spreads, how it behaves, how best to treat the disease and how to protect against it—that researchers globally are striving to answer. A better understanding of the virus and the disease will affect China’s lifting of social-distancing mandates and the foreign-visa travel ban.

Similarly, global GDP growth will affect how much fiscal stimulus China provides and for how long. Disruptions to global production and supply chains compel China to be adaptable and affect how it supports its industries. And global governance impacts China’s behavior as it incurs blame for the origin of the disease, reacts to growing anti-China sentiment, collaborates with the World Health Organization and helps the global community create new rules of order for pandemics.

We don’t yet know how these variables will play out. But as participants in a massive global experiment, countries can look to one another to observe and learn.

Mo Ji is Chief Economist—Greater China, at AB.

The views expressed herein do not constitute research, investment advice or trade recommendations and do not necessarily represent the views of all AB portfolio-management teams. Views are subject to change over time.

This post was first published at the official blog of AllianceBernstein..