by Craig Basinger, Chris Kerlow, Derek Benedet, Alexander Tjiang, RichardsonGMP

Performance chasing is perhaps one of the biggest detractors from the long-term results of most investor portfolios. Despite “past performance of securities is no guarantee of future results” being one of the most pervasive disclaimers in the financial industry, it does not seem to sink into investor behaviour. Many decisions and money flows follow a rather predictable path, chasing performance. A number of behaviours feed into this performance-sapping habit.

Fear of missing out (FOMO) is a big one. Looking at great returns, you want to participate so you jump in. Trend-chasing bias encapsulates performance chasing well; we often believe that what has been occurring (in this case above- average performance) will continue. Believing what is happening today will continue tomorrow is a good bias in most facets of life, not as much with investing.

The fact that performance chasing impacts all of us to a degree is not lost on the fund manufacturers or other financial advice channels. Fund companies often incubate many funds with just over the regulatory minimum number of investors and assets for years before marketing the fund. I will let you guess which incubated funds they choose to run with. And with RSP season a few months away, you better believe the Path (that is, the underground walkway in Toronto) will be plastered with mountain charts for certain funds showing their past wealth creation, tugging on those performance-chasing behavioural urges.

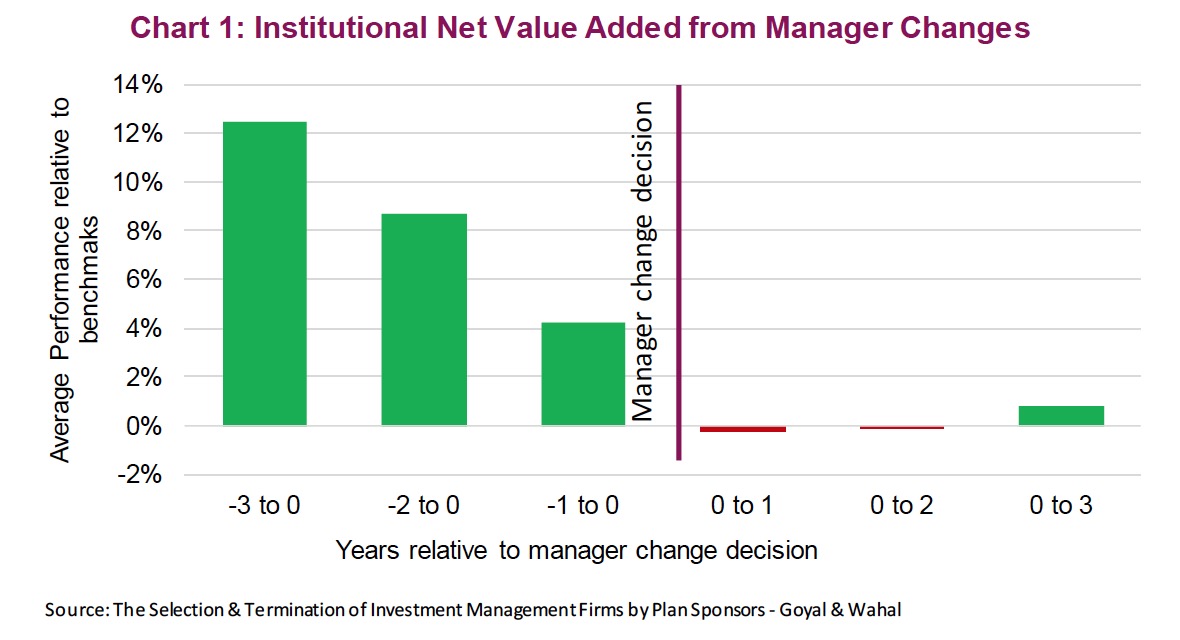

Don’t feel bad though, it is not just the individual investor that falls prey to performance chasing. Goyal & Wahal created a white paper looking at institutional investors’ manager decisions. These are pension, endowment and foundation funds. Low and behold, even the institutional allocators suffer from performance chasing. Chart 1 is the average manager performance compared to their appropriate benchmark prior to being added and following being added to a portfolio. Clearly managers are being added that had great historical performance in their respective category over the past few years. This trend does not appear to have continued after the allocation to the new manager was made, on average.

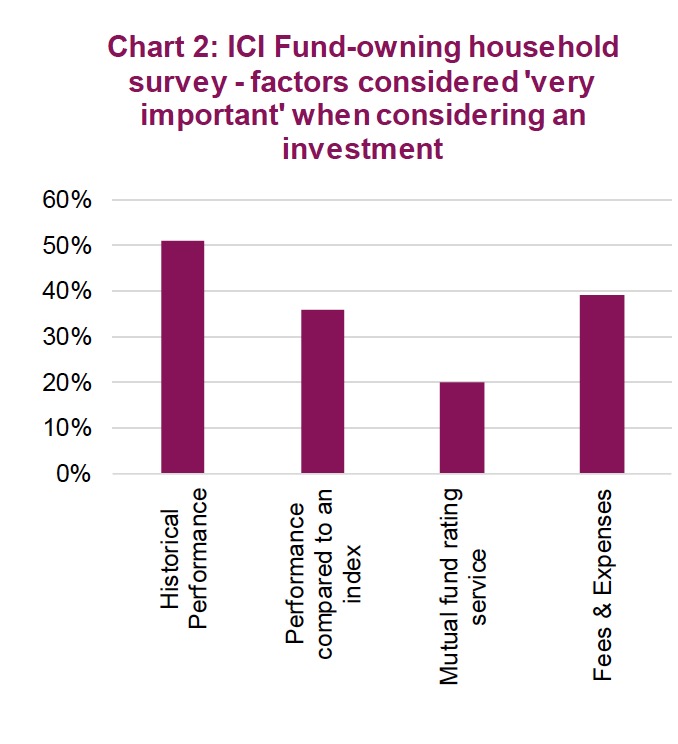

An ICI Fund survey of individual investors supported the fact that historical performance continues to be the primary driver of investment decisions. Historical performance was deemed to be ‘very important’ in 50% of the decisions, the most prominent response. This was followed by ‘performance compared to an index’ and ‘fees’. It would have really been nice to see some investors highlight how the fund fits into their overall portfolio to achieve their long-term plans. Maybe next survey.

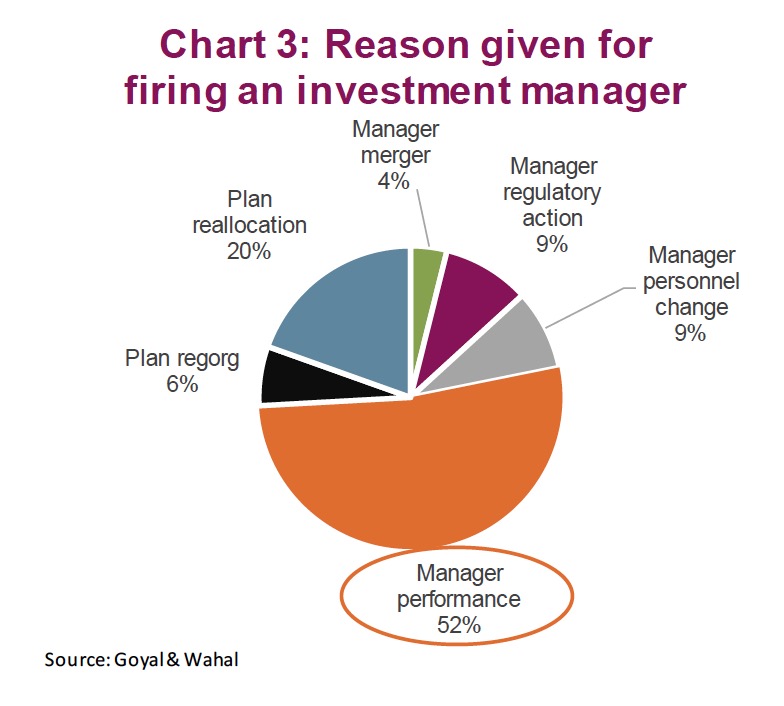

Similar patterns of return chasing appeared evident in firing managers as well. In the Goyal & Wahal analysis of institutional money manager decisions, performance was the reason behind a manager termination over 50% of the time. To make matters worse, the underperformance of the terminated managers turned to outperformance in the years after being fired, on average.

In summary, even the sophisticated institutional asset allocators with their experienced consultants suffer from performance chasing: Adding managers that had been crushing it only to see their performance mean revert; and removing managers that have been suffering only to see their performance improve after firing (on average). Institutions and individuals alike tend to be impatient, react to performance and want to take action, which all contributes to performance chasing.

Investment process to the rescue

Clearly, we all suffer from performance chasing. It is often easiest to simply terminate or sell underperforming investments and move on to ones that appear to be doing better – the grass is always greener. For those providing advice, this can also help protect your career, finding a scapegoat for poor performance and taking action resonates with most investors. Unfortunately, this can and often does hurt performance. So, what can we do on the advice side of things?

Define the investment philosophy – For those providing advice, if you can define your investment approach in a way that is clear and easy to understand, this will help resiliency and become less susceptible to making rash decisions when something is not working. Understanding that some investment strategies will work well during certain periods in the market cycle and underperform in others is key. That, after all, is the key to diversification. If investors and clients can clearly understand your investment philosophy, it will help their mindset as well.

Avoid episodic portfolio reviews – If portfolio reviews occur once a quarter or even worse once a year, there will be a lot of pressure to make changes at that point in time. Institutions suffer from this when they have quarterly investment committee meetings, bringing together all the decision makers, during which portfolio recommendations are often presented and acted upon. Portfolio changes should not be dictated by the timing of a meeting – it is a full-time job. Changes should be made when the market changes or the outlook has been revised.

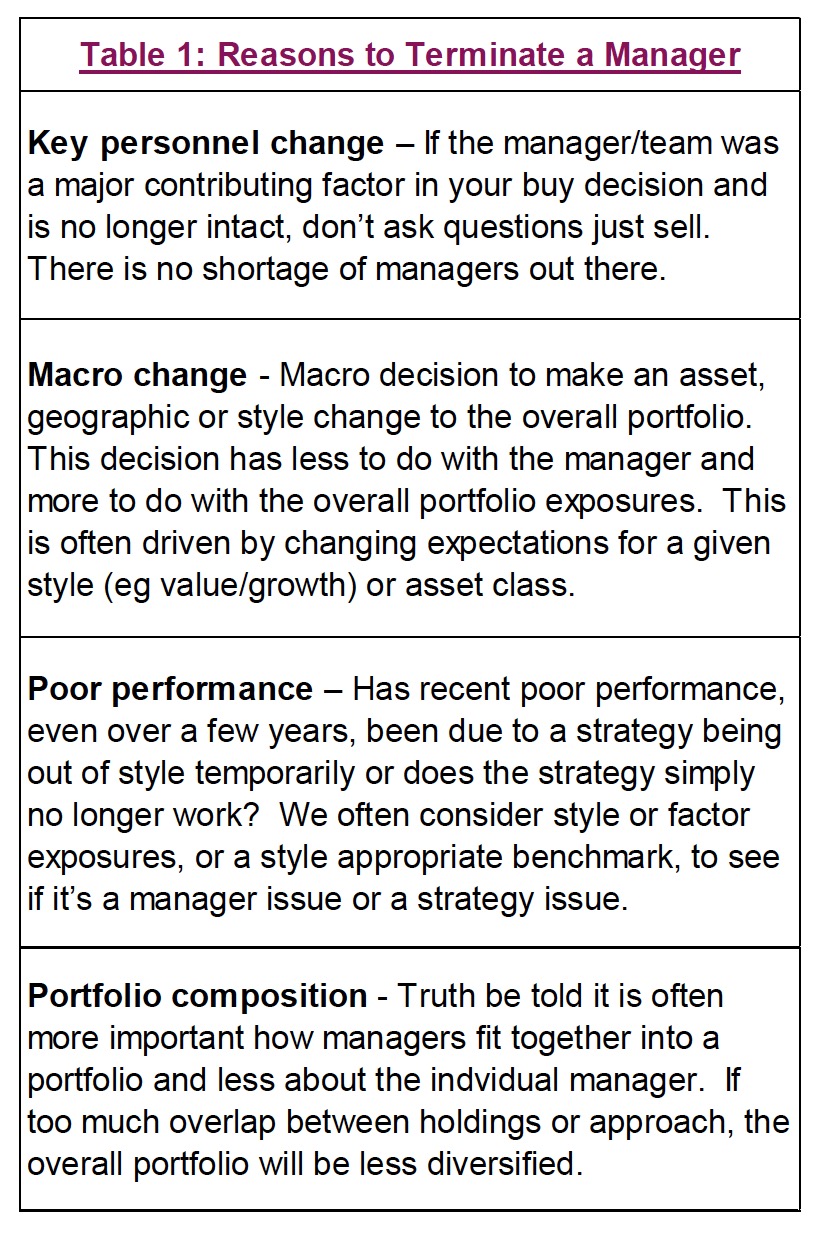

Making manager changes and why – Have a process or checklist for making manager changes and communicating this with clients. Developing such a process when not in the throws of dealing with an underperforming manager can lead to a system that should result in better decision making. In Table 1, we share a few points to consider when contemplating a manager termination. This content is a very abbreviated list of some of the things we consider in our Managed Portfolios and the Partnership Program services.

Conclusion

Having a clear investment process, developed to improve your decision making, can go a long way to avoiding making costly manager change mistakes. We would not recommend anyone ignore past performance, but it should be analyzed in light of the market environment and an investment’s role in the entire portfolio. Develop a process, write it down and always look for ways to improve.

Source: All charts are sourced to Bloomberg L.P. and Richardson GMP unless otherwise stated.

This publication is intended to provide general information and is not to be construed as an offer or solicitation for the sale or purchase of any securities. Past performance of securities is no guarantee of future results. While effort has been made to compile this publication from sources believed to be reliable at the time of publishing, no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to this publication’s accuracy or completeness. The opinions estimates and projections in this publication may change at any time based on market and other conditions, and are provided in good faith but without legal responsibility. This publication does not have regard to the circumstances or needs of any specific person who may read it and should not be considered specific financial or tax advice. Before acting on any of the information in this publication, please consult your financial advisor. Richardson GMP Limited is not liable for any errors or omissions contained in this publication, or for any loss or damage arising from any use or reliance on it. Richardson GMP Limited may as agent buy and sell securities mentioned in this publication, including options, futures or other derivative instruments based on them. Richardson GMP Limited is a member of Canadian Investor Protection Fund. Richardson is a trademark of James Richardson & Sons, Limited. GMP is a registered trademark of GMP Securities L.P. Both used under license by Richardson GMP Limited. ©Copyright October 28, 2019. All rights reserved.

Copyright © RichardsonGMP