by Maarten Bloemen, Franklin Templeton Investments

The most recent report from the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) leaves little doubt about both the dangers and the rapid advance of climate change. The IPCC, a distinguished international group of 195 of the world’s leading climate scientists, has been studying climate change intensively since 1988 and has issued an ongoing series of peer-reviewed reports. Its most recent comprehensive report, issued in late 2018 and two years in the making, confirmed that global warming was proceeding much faster than previous modeling had suggested.

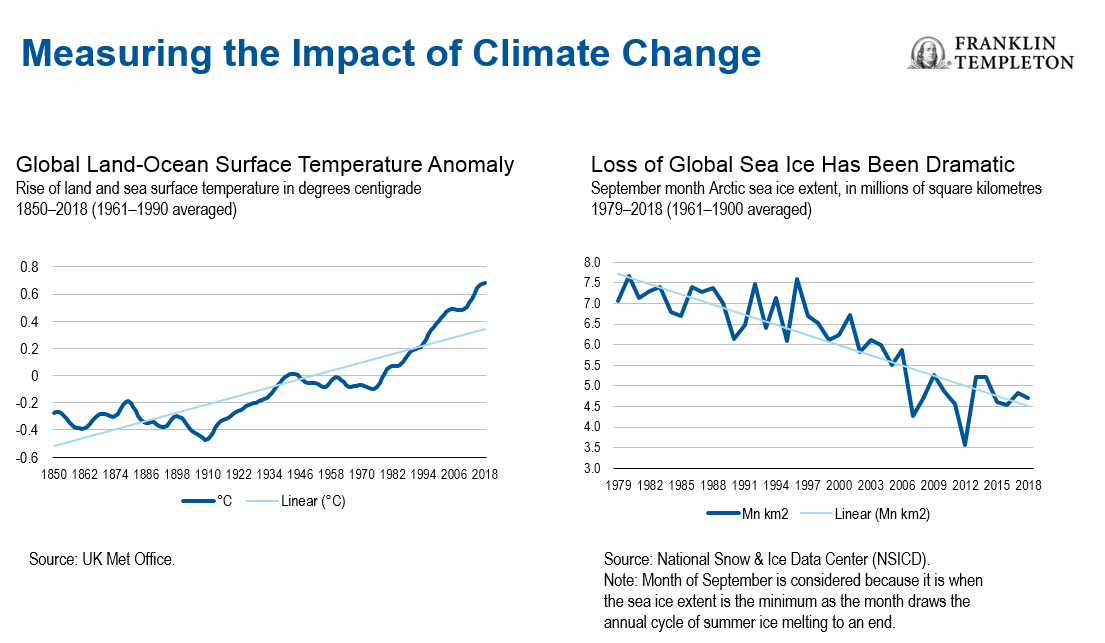

The report further noted that the most recent decade had seen a record-breaking volume of violent storms, floods, droughts, forest fires and melting sea ice. The report also warned that average global temperature rises masked much greater warming in particular regions, notably the Arctic and Antarctica, where glacier and ice melting could have a calamitous impact on rising sea levels.

Importantly, the report also tightened the aspirational target of a 2° Celsius warming (or less) agreed at the historic Paris Summit in 2015 to a more stringent 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels. Ominously, it warned that, based on current emissions trajectories, the “carbon budgets” required to keep warming at or below that level could be exhausted in as little as 11 years.1

A recent report by the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) underscores the human impact of a changing climate, finding that in 2018 alone, some 62 million people were directly affected by climate change, including the forced relocation of 2 million “climate refugees”.2 Moreover, the trends of the last few years have been particularly worrisome; after two consecutive years of declines, global CO2 emissions increased in both 2017 and 2018. In 2018, emissions grew by 1.77%, which was 70% higher than the average increase over the past decade.3

While considerable uncertainties remain, there is little doubt that the climate is changing and that human activities are contributing to that change. In addition to its broader societal significance, a changing climate has major implications for investors who are well-positioned to support a constructive response to climate change—and to potentially profit from doing so. Ultimately, we believe there are at least six compelling reasons for investors to take climate change seriously, which we will outline below.

1.Responding to a Global Economic and Industrial Restructuring

Most climatologists believe that, ceteris paribus, we are currently on course for an increase of 3–4°C, well in excess of the 2°C target of the Paris Agreement and the subsequent 1.5°C target of the IPCC. Even with the dramatic improvements that will be required to reach international climate targets, success is not guaranteed.

Reducing greenhouse gas emissions by recommended levels will require a dramatic rebalancing of the entire energy value chain towards zero and low emission fuels. Its effects will not be limited to high-impact sectors such as coal, oil and gas, mining, utilities and manufacturing; the competitive dynamics of nearly every industry and business will be affected. The scope and scale of the changes required will be truly transformational.

We believe the costs of failing to act are enormous: investment firm Schroders estimates our current 4°C trajectory would create over US$20 trillion in economic losses by the end of the century. To put this into context, this would represent permanent economic damage on a scale three or four times larger than that inflicted by the 2008 global financial crisis.4

Perhaps the most important implication of global industrial and economic restructuring for investors is this: the entire basis of corporate competitive advantage is being recalibrated, and companies that can create the greatest economic value with the fewest carbon emissions are already reaping the benefits.

This pursuit of greater carbon efficiency can be seen in the move towards low-emission and electric cars by mainstream auto-makers; the building and retrofitting of “green” and energy-efficient buildings; the greater market share and competitiveness of renewable energy sources, including wind and solar; and the public commitments of oil majors to reduce their carbon footprints significantly.

As with any major industrial restructuring, however, the shift to a lower-carbon energy world will create both winners and losers, and it is critical that investors are able to distinguish between the two. We believe that the upside dimension is too often overlooked in discussions about climate change.

To take just two examples, the market for electric vehicles (EV) grew by an impressive 54% in 2017 alone,5 and the International Energy Agency (IEA) predicts that solar, wind and other renewable sources will account for 50% of all new power generation by 2050, compared with 25% at present. By contrast, it is expected that fossil fuels will be reduced to only a 29% share of power generation by 2050, compared with their current share of 63%.6

Companies standing to benefit from this overall energy restructuring can be grouped into two broad categories: solution providers and transitional and resilient companies.

- Solution providers: companies providing products and services that directly or indirectly reduce global emissions, improve resource efficiency, and/or protect against the physical consequences of climate change. Examples of such companies include manufacturers of cathodes for EV batteries, developers of low-energy lighting, smart meter manufacturers, developers/operators of offshore wind parks and producers of wind turbines. This group also includes facilitators of low-carbon transition, whose products and services expand the scope and power of those providing direct solutions, such as communications networks, cloud-based software developers to accelerate energy efficiency solutions, specialist waste and water engineers and climate finance providers.

- Transitional and resilient companies: companies that have 1) relatively low carbon and resource intensity to begin with, such as pharmaceuticals, or 2) those with significant emissions or resource intensity which are making industry-leading progress in reducing them. This includes companies in traditionally high-emitting sectors that are reducing their emissions and resource use faster than their industry competitors, such as freight and logistics companies or shopping mall real estate investment trusts (REITs).

2. Maximizing Risk-Adjusted Financial Performance

We believe a rigorous approach to fundamental analysis, deep knowledge of companies and industries, engagement with management teams, and, ultimately, effective stock selection, allows us to identify and manage environmental risks and the potential opportunities. This includes a focus on buying undervalued companies offering products and solutions to help others reduce emissions and increase energy efficiencies, as well as those effectively transitioning to a lower-carbon future.

For many years, mainstream investment “wisdom” held that any consideration of ESG (environmental, social and governance) factors was either irrelevant or actually harmful to financial performance. More recently, however, this conventional wisdom is being turned on its head by a variety of empirical performance studies by both academics and formerly skeptical practitioners.7

In addition, a “meta-study” of over 200 individual studies undertaken by Oxford University provides even more evidence of the impact of ESG factors on financial performance. Among the key results: 80% of the studies showed that superior corporate environmental performance produced better share price performance and 88% showed that strong ESG practices resulted in better operating performance as measured by conventional accounting indicators.8

The studies demonstrate that integrating material ESG factors into investment analysis can lead to improved risk-adjusted performance, and certainly does not detract from it.

In our view, this research provides compelling evidence that properly integrated, robust ESG research can indeed improve long-term risk-adjusted returns. And it is generally agreed that the most critical, high-impact, and multifaceted of all of the myriad ESG issues today is climate change.

What’s more, as climate change becomes ever more pronounced, there is every reason to believe that it will become an even more critical factor in companies’ competitive and share price performance in the future. Investing in companies today that have a head start in addressing climate risks and opportunities should position portfolios well for a future in which this critical theme assumes ever-increasing importance.

Different Types of Climate Risk for Investors

In our view, climate change is creating at least four kinds of risk for both companies and their investors. Understanding these risks helps us assess how effectively individual companies are addressing them, and thereby improving their chances of long-term success:

- Physical Risk: Climate-driven events such as violent storms, flooding and droughts have already disrupted important international supply chains. One early example was the negative impact on semiconductor companies of floods in Thailand in 2011. One of the most pervasive and serious physical threats from climate change is sea-level rise. The combination of ocean warming and melting glaciers and ice sheets in Greenland and Antarctica has already raised average sea levels by roughly three inches over the past 25 years.

- Regulatory, Policy and Taxation Risk: A growing array of tightening national, regional and local regulations (such as tougher emission controls, energy efficiency standards for buildings and fuel efficiency standards for automobiles) is affecting companies from Stockholm to Singapore, and is likely to become only more demanding going forward. Similarly, there is an inexorable movement towards higher taxation on carbon emissions, led by the European Union (EU).

- Transition and Competitive Risk: Climate change is already beginning to rewrite the rules of competitive advantage in a number of key industries. In the auto sector, for example, companies without a strong presence in the electric/low-emission vehicles market will be at a growing disadvantage. In the energy sector, companies with reserves of “unburnable carbon” (because of new regulation and changing competitive dynamics) may be stuck with “stranded assets” that cannot be developed economically.9

- Reputational Risk: Given the ongoing, long-term transition towards a low-carbon global economy, companies seen as “part of the problem” face growing reputational damage from newly active stakeholders. Some of the oil and gas majors, for example, are facing both customer and investor boycotts, as well as a growing backlash from institutional shareholders. Significant divestments from the fossil fuel sector are already underway.

It is important to note that the impact of climate factors is not limited to downside risks; they can also lead to investment opportunities on the upside. Our global climate change approach is focused on both dimensions.

3. Addressing Environmental and Social Imperatives

As at late 2018, human activities were emitting over 37 billion tons of carbon dioxide equivalents into the atmosphere every year. The adverse environmental and social impacts which climate change is already beginning to generate include:

- Increased frequency and intensity of extreme weather events such as hurricanes, tornados, droughts, wildfires, heatwaves and floods.

- Sea level rises and increased coastal flooding.

- The migration of human, animal and plant diseases into new territories where warmer temperatures are more accommodating.

- The creation of “environmental refugees” in areas ranging from Bangladesh to the Middle East to Africa: extreme weather phenomena such as hurricanes, coastal flooding, droughts and changes to seasonal weather patterns have displaced an annual average of over 20 million people since 2008, according to the UN Refugee Agency.10

- The exacerbation of armed conflict: in a recent report, US military experts have argued that climate-induced droughts, for example, have served as “threat multipliers,” aggravating violent conflicts in areas including Darfur, Somalia, Iraq and Syria.11

It is also important to note that the adverse environmental, economic and social impacts of climate change are highly likely to hit vulnerable populations disproportionately. Accordingly, the importance of a just transition to a low-carbon economy is receiving greater visibility and priority in the global climate dialogue.

Collectively, investors will play an important role in determining whether these challenges are met.

4. Responding to Growing Client and Stakeholder Demand

In recent years, there has been a sea change in attitudes and priorities among investors. Both their concerns over climate change and their expectations for asset managers to respond to it have increased. One measure of the scale of the potential impact of investors is the growth of collective climate initiatives by institutional investor groups. Perhaps the largest and certainly the longest-established of these organizations is the Carbon Disclosure Project, now renamed the CDP. A non-profit organization launched in 2002, the CDP has been administrating in-depth, systematic surveys of major corporations worldwide, seeking to illuminate their carbon emissions, carbon management regimes, future emission reduction targets and attempts to capitalize on commercial opportunities.

Today, the CDP brings together roughly 530 major investors worldwide with combined assets under management in excess of US$100 trillion and receives and analyses information from over 7,000 companies. As a result, it is arguably the largest and most reliable source of company data about climate change in the world.

The Institutional Investors Group on Climate Change (IIGCC) represents a collaboration of over 170 major European asset owners and investors with combined assets of over €23 trillion. In addition to its activities to promote and disseminate best practice among its members, the IIGCC and its secretariat engage intensively with the European Commission (EC), perhaps the leading policy-making body in the world on climate change. The IIGCC was a major factor in the success of the 2015 Paris Agreement; without its active participation and advocacy, it is doubtful such positive results could have been achieved.

In a similar vein, the Climate Action 100+ group, with some 360 investor members and over US$34 trillion in combined assets, has been created with the explicit mandate of putting pressure on the 100 largest “systemically important corporate emitters” to adopt meaningful climate action.

All three organisations include some of the largest and most influential institutional investors in the world, and Franklin Templeton is in the process of joining them. Our membership in these organisations will give us access to evolving best practices globally, strengthening our analytical capabilities and policy engagement efforts. In the case of the CDP, our membership will also give our analysts and portfolio managers direct access to the largest collection of granular, company-specific data in the world, which includes both quantitative and qualitative information.

One of the most powerful drivers of the dramatic growth of retail demand for sustainable investing has been the emergence of millennials as a significant force in the investment world. A recent study of 1,000 individual American investors by Morgan Stanley found that millennials were twice as likely as regular investors to favour sustainable solutions. The percentage of millennials who were “very interested” in such solutions doubled from 2015 to 2017, and an impressive 90% of them wanted a sustainable option available in their retirement investment plans.12

Climate change, which barely registered with sophisticated investors a decade ago, has today become one of the most critical issues confronting asset managers and their clients.

5. Meeting Tightening Regulatory and Transparency Requirements

The growing public and governmental concern over climate change has been accompanied by a proliferation of legislation, regulation and, in many jurisdictions, taxes on carbon emissions. Indeed, in the 20-year period between 1997 and 2017, there was a 20-fold increase in the number of climate-change laws worldwide. Today, there are more than 1,200.13

Much of the emphasis of the new regulations is on making climate risk exposures, carbon emissions, and management strategies more transparent for both companies and investors. For investors, a precondition for any corporate climate assessment is the availability of robust data and corporate information. In many jurisdictions, such disclosure is entirely voluntary, but it is increasingly becoming legally prescribed.

Pressure on investors to disclose standardized climate data has so far lagged behind similar disclosures by corporations, but it is nevertheless intensifying, and will likely continue to do so in the future.

One of the most ambitious recent regulations is France’s energy transition law, Article 173, which requires major investors in that country to conduct and publish an annual assessment of the level of climate risk in their investment portfolios. Similarly, in Sweden, public pension funds are now legally required to assess and publish the carbon footprints of their portfolios.

In 2018, the EU announced its intention to explicitly mandate the consideration of ESG issues (including climate change) by investors, and similar legislation is also under consideration in the United Kingdom.

6. Fulfilling Changing Fiduciary Responsibilities

Fiduciary responsibility is the set of legal and financial obligations on investors as part of their “duty of care” to the owners of the assets with which they have been entrusted. The trustees and/or managers have a fiduciary responsibility to the ultimate owners of the assets to manage them prudently, and exclusively in the beneficiaries’ best interests. The nature of these responsibilities is typically specified in legislation and has also been elaborated in case law over previous centuries.

It is, however, important to note that the concept of fiduciary obligations is not a static one; as societal values and priorities change and evolve, so do the extent and requirements of fiduciary responsibility. In the case of climate change (and ESG more broadly), the concept of fiduciary responsibility is virtually being turned on its head.

For many years, one of the greatest obstacles to the growth of responsible and sustainable investment was the widespread—if mistaken—belief that addressing ESG issues was incompatible with investors’ fiduciary responsibilities. Indeed, investors felt that ESG considerations were at most immaterial to companies’ financial performance. As a result, it was believed that integrating ESG factors would limit an investor’s opportunity set, thereby hurting returns and breaching fiduciary responsibilities.

As we now know, this view was not based on any empirical analysis or evidence, but was predicated on a number of false assumptions about what “ESG investing” actually entailed. Nonetheless, these views were widely held, and in some cases enshrined in legislation and regulation. They were arguably the single greatest obstacle to ESG investing becoming mainstream.

All of this, however, has begun to change, and the notion of fiduciary duty is quickly becoming the opposite of its earlier incarnation; today, it is increasingly accepted that the failure to address ESG constitutes an abdication of fiduciary responsibility. This new interpretation is itself now beginning to be enshrined in legislation, regulation and actual investment practice.

Want even more insight on this topic? Check out the team’s topic paper, “Discovering Value in Climate-Change Investing.”

Important Legal Information

This material is intended to be of general interest only and should not be construed as individual investment advice or a recommendation or solicitation to buy, sell or hold any security or to adopt any investment strategy. It does not constitute legal or tax advice. This is not a complete

analysis of every material fact regarding any industry, security or investment and should not be viewed as an investment recommendation. This is intended to provide insight into the portfolio selection and research process. Factual statements are taken from sources considered reliable, but have not been independently verified for completeness or accuracy. These opinions may not be relied upon as investment advice or as an offer for any particular security. Past performance does not guarantee future results.

The views expressed are those of the investment manager and the comments, opinions and analyses are rendered as at publication date and may change without notice. The information provided in this material is not intended as a complete analysis of every material fact regarding any country, region or market.

Data from third party sources may have been used in the preparation of this material and Franklin Templeton Investments (FTI) has not independently verified, validated or audited such data. FTI accepts no liability whatsoever for any loss arising from use of this information and reliance upon the comments opinions and analyses in the material is at the sole discretion of the user.

Products, services and information may not be available in all jurisdictions and are offered outside the U.S. by other FTI affiliates and/or their distributors as local laws and regulation permits. Please consult your own professional adviser or Franklin Templeton institutional contact for further information on availability of products and services in your jurisdiction.

What Are the Risks?

All investments involve risks, including possible loss or principal. The value of investments can go down as well as up, and investors may not get back the full amount invested. Stock prices fluctuate, sometimes rapidly and dramatically, due to factors affecting individual companies, particular industries or sectors, or general market conditions. Special risks are associated with foreign investing, including currency fluctuations, economic instability and political developments. Investments in emerging markets involve heightened risks related to the same factors, in addition to those associated with these markets’ smaller size and lesser liquidity.

_______________________

1. Source: Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), “Special Report: Global Warming of 1.5°C,” October 2018.

2. Source: World Meteorological Organization, “State of the Global Climate in 2018,” March 2019.

3. Source: International Energy Agency, Global Energy and CO2 Status Report, 2018.

4. Source: Schroders, Schroders Climate Dashboard, October 2018.

5. Source: International Energy Agency, “Global EV Outlook 2018,” May 2019.

6. Source: Ibid, World Energy Outlook, 2018.

7. Source: AIMA Research, “ESG’s Evolving Performance”; MSCI, “How Markets Price ESG,” July 2018; J.P. Morgan, “ESG: Environmental, Social, and Governance Investing,” March 2018; and State Street Global Investors, “IQ Insights,” 2018.

8. Source: Oxford University, Gordon Clark et al, “From the Stockholder to the Stakeholders,” March 2015.

9. Source: The concept of “stranded assets” has been popularized by the influential NGO Carbon Tracker. See Carbon Tracker, Unburnable Carbon 2013: Wasted Capital and Stranded Assets, 2013.

10. Source: UNCHR, November 2016.

11. Source: U.S. Department of Defense, Report on “Effects of a Changing Climate,” January 2019.

12. Source: Morgan Stanley, “New Data from Individual Investors,” Sustainable Signals, 2017.

13. Source: Grantham Institute on Climate Change and the Environment et al., Global Trends in Climate Change Legislation and Litigation, 2017.

This post was first published at the official blog of Franklin Templeton Investments.