Raymond James' Chief Economist, Scott Brown, discusses current economic conditions.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics reported that nonfarm payrolls rose by 130,000 in its initial estimate for August, even as temporary hiring for the 2020 census added 25,000. Private-sector payrolls rose by 96,000, leaving the three-month average at 129,000 (a +145,000 average for the first eight months of 2019, vs. +215,000 in 2018). While the recent trend in job growth is widely seen as “slow,” it’s still more than what is needed to absorb new entrants into the workforce. This slowing in job growth appears to be natural – that is, reflective of a further tightening of labor market conditions (a lack of skilled workers). This view is supported by faster wage growth. For production workers, average hourly earnings were reported to have risen 3.5% year-over-year in August.

The BLS recently updated its 10-year employment projections. The BLS expects that the economy will add 8.4 million jobs between 2018 and 2028. That averages out to 70,000 per month – significantly slower than in recent years. The slower employment outlook is driven by the demographics, not economic weakness. Granted, there may still be some slack in the labor market, which would permit job growth beyond a long-term sustainable rate in the near term, but it will eventually slow. Immigration had been expected to account for about 40% of labor force growth over the next decade. However, under the current administration, expectations for legal immigration have been cut in half.

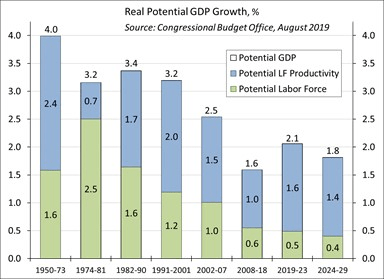

Output is the amount of labor input times productivity (output per worker). Hence, growth in real output will equal job growth plus productivity growth. If labor force growth is 0.5% per year and productivity growth is 1.0-1.5%, then potential real GDP growth ought to be 1.5-2.0%.

The BLS projects job growth by sector. Employment in health care is expected to lead the way over the next 10 years, reflecting the needs of an aging population, followed by professional and business services, leisure and hospitality, and construction. Manufacturing, federal government, utilities, and wholesale and retail trade are expected to shed jobs – reflecting advances in technology (robotics, the rise of internet commerce).

In its updated Budget and Economic Outlook, the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office revised its estimate of potential GDP (encompassing the annual benchmark revisions to the National Income and Product Accounts made in late July). The CBO views the economy as being currently beyond full employment, with the output gap (the difference between GDP and potential GDP) at +0.8% (vs. -5.9% in the depth of the 2007-09 recession). While there is considerable uncertainty in estimating potential GDP, a number of senior Fed officials are likely to agree with this assessment. In this scenario, a period of below-trend growth would be necessary to bring GDP back to its potential, to put the economy on an even keel. Soft landings are difficult to achieve, but this year’s trade policy uncertainty and slower global growth have taken a role that would normally fall to the Fed (which would otherwise have raised rates to cool economic growth). The Fed had been raising short-term interest rates over the last couple of years, but monetary policy was still seen as accommodative after the rate hike last December – closer to neutral, but not quite there.

Real GDP rose at a 2.0% annual rate in the 2nd estimate for 2Q19 (vs. +2.1% in the advance estimate). The story behind the numbers was the same. Growth was isolated in just two sectors, consumer spending and government. The estimate of consumer spending growth was revised higher

(to a 4.7% annual rate, vs. +4.3% in the advance estimate) – certainly strong, but that followed two soft quarters (+1.4% in 4Q18 and +1.1% in 1Q19). Business fixed investment fell at a 0.6% annual rate (same as in the advance estimate), with weakness in mining structures (which includes energy exploration) and transportation equipment (which includes problems at Boeing). Residential fixed investment (mostly homebuilding) fell at a 2.9% annual rate, the sixth consecutive quarterly decline, although some improvement is seen in the near term. Slower inventory growth subtracted 0.9 percentage point from overall GDP growth, while net exports (a wider trade deficit) subtracted 0.7 percentage point.

Recent economic data reports have painted a mixed picture of the U.S. economy. The ISM Manufacturing Index fell to 49.1 in August, with new orders, production, and employment all below the breakeven level. The ISM Non-Manufacturing Index rose to 56.4, with pickups in business activity and new orders, but some slowing in employment. The ISM surveys are diffusion indices, and don’t measure actual activity, but trends in these figures give a sense of direction. The Fed’s industrial production measure had peaked in December (falling by 1.6% to July), so a contraction in manufacturing has been underway for some time. Yet, it’s not a steep decline. We’ve often had modest recessions in the factory sector without a recession in the overall economy (however, a recession in the overall economy has always coincided with a downturn in manufacturing output).

U.S. manufacturers use parts and supplies from around the world and trade policy has had a dampening impact on activity. In particular, the May 10 escalation in tariffs (which went from 10% to 25%, and possibly to 30% in a few weeks) raised input costs, which have been difficult to pass along, squeezing profit margins. The September 1 tariffs (15% on the remaining $300 billion in Chinese imports, 60% of which were postponed to mid-December) falls mostly on consumer goods. To date, trade policy uncertainty does not appear to be large enough (by itself) to push the U.S. economy into a recession. However, there is increasing anecdotal evidence that tariffs and trade policy uncertainty are dampening the growth outlook. Firms can’t get price quotes or supply commitment for next year, making it difficult to plan. While investors are optimistic that a trade deal can be reached, a complete agreement between China and the U.S. is looking remote. Still, avoiding a further escalation might be enough, at least over the near term, and investors have focused on achieving a mini-deal.

In cutting the federal funds target range in late July, Fed Chair Powell cited the impact of trade policy uncertainty and softer global growth, the downside risks that these factors posed, and the low trend in inflation. President Trump ratcheted up trade tensions the day after the late-July Federal Open Market Committee meeting, the global economic data have been generally weaker, and the core PCE Price Index is expected to continue trending below the Fed’s 2% goal. Consequently, the FOMC lowered the target range for the federal funds rate by another 25 basis points on September 18, to 1.75-2.00%.

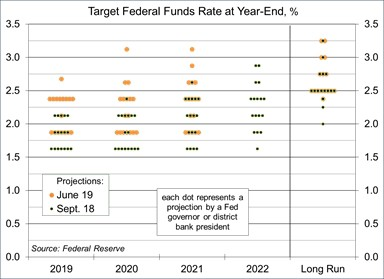

For some time, Fed officials have been divided on the appropriate course of monetary policy. The revised dot plot (the projections of each senior Fed official of the appropriate yearend level of the federal funds rate) showed that five of the 17 officials did not want to lower rates at the September 17-18 meeting, five did not expect any further rate cuts this year (beyond the September 18 cut), and seven anticipated one more rate cut. While all 17 Fed officials participate at the policy meeting, only 10 are members of the FOMC (which sets policy). Two FOMC members formally dissented in favor of keeping rates steady in September and it’s likely that the other hawkish dots in the dot plot represent non-voting officials. One FOMC member dissenting in favor of a 50-bp move, and it’s likely that other dovish dots represent voting FOMC members. Hence, another cut is more likely than not. Still, there is considerable uncertainty surrounding each dot, and future policy decisions will remain data dependent.

The more hawkish Fed officials believe that the economy is already beyond full employment and that there is a threat of higher inflation, while the more dovish officials believe that the downside risks need to be addressed, especially given the proximity to the zero lower bound. Fed Chair Powell had described the July 31 rate cut as “a mid-cycle adjustment.” When asked whether he would describe this latest rate cut in the same way, he demurred. While the dot plot suggests that these are “insurance moves” taken to insure against downside risks, not the start of a long easing cycle, Powell indicated that “if the economy does turn down, then a more extensive sequence of rate cuts could be appropriate.” He added, “We don’t see that, but we would certainly follow that path if appropriate.”

During the week of the FOMC meeting, the Fed had to deal with a liquidity squeeze in the repo market. The repo market is huge, with daily volumes of around $4 trillion. In a repurchase operation (repo) a firm borrows funds short-term by selling a security and agreeing to repurchase it later (typically overnight). There was an extra need for such funding on September 16, reflecting corporate tax payments and Treasury auction settlements. However, demand for funds was stronger than expected and the effective federal funds rate rose above the top of its target range. It’s unclear why banks with excess reserves did not step in to address the market’s needs. By the end of the week, the New York Fed announced that it would conduct a series of overnight and term repurchase agreement operations through October 10 “to help maintain the federal funds rate within the target range.”

Chair Powell downplayed the squeeze as being technical in nature, “with no implications for the economy or the stance of monetary policy.” However, the issue reflects financial market participants’ ongoing concerns about the Fed’s ability to maintain an adequate level of reserves. Bank reserves fell as the Fed unwound its balance sheet and the Fed shifted its policy focus to bank reserves (rather than the specific size of the balance sheet). That unwinding has ended (two months earlier than planned). The Fed expected to eventually begin “organic QE,” growing the balance sheet in line with the overall economy and the need for reserves. Obviously, this would be on a much smaller scale that the Fed’s previous asset purchase programs, but it should be welcomed by the financial markets. In his post-FOMC press conference, Powell suggested that organic QE may come sooner. Powell emphasized, that “consistent with our decision earlier this year to implement monetary policy in an ample reserves regime, we will, over time, provide a sufficient supply of reserves so that frequent operations are not required.”

Meanwhile, U.S. economic data reports are likely to remain mixed. Consumer spending, 68% of Gross Domestic Product, should remain supported by strong household sector fundamentals (job gains and wage growth). Business fixed investment is expected to be restrained by trade policy uncertainty, slower global growth, geopolitical tensions, and political uncertainty at home. The outlook for homebuilding has turned positive, but residential fixed investment accounts for only about 3.7% of GDP – hence, is not likely to move the needle much on the overall economy. Should trade policy uncertainty and concerns feed through more noticeably to the labor market, the Fed would be expected to respond more aggressively.

The opinions offered by Dr. Brown should be considered a part of your overall decision-making process. For more information about this report – to discuss how this outlook may affect your personal situation and/or to learn how this insight may be incorporated into your investment strategy – please contact your financial advisor or use the convenient Office Locator to find our office(s) nearest you today.

All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the Research Department of Raymond James & Associates (RJA) at this date and are subject to change. Information has been obtained from sources considered reliable, but we do not guarantee that the foregoing report is accurate or complete. Other departments of RJA may have information which is not available to the Research Department about companies mentioned in this report. RJA or its affiliates may execute transactions in the securities mentioned in this report which may not be consistent with the report's conclusions. RJA may perform investment banking or other services for, or solicit investment banking business from, any company mentioned in this report. For institutional clients of the European Economic Area (EEA): This document (and any attachments or exhibits hereto) is intended only for EEA Institutional Clients or others to whom it may lawfully be submitted. There is no assurance that any of the trends mentioned will continue in the future. Past performance is not indicative of future results.