by Elga Bartsch, PhD, Blackrock

Elga discusses the reasons the Fed is conducting a major monetary policy review. This is the second post in a series of blogs on the Fed and inflation expectations.

An in-depth policy review at the Federal Reserve is in full swing, and the central bank could announce significant changes to its monetary policy approach early next year.

We examined some of the economic and market implications of this review in a recent post The implications of a potential Fed policy shift. Here we take a deeper dive into why the Fed is reviewing its monetary policy strategy, the next in a series of blogs on the Fed and inflation expectations.

The Fed’s review aims to address the challenges faced by central banks in the aftermath of the global financial crisis, as we write in our Macro and market perspectives Fed to raise its inflation game? These challenges are rooted in falling neutral interest rates–rates that would neither stimulate nor hold back economic growth–and declining inflation expectations. Both of these could limit the ability of monetary policy to counter future downturns.

A decline in the neutral rate of interest implies that average policy rates are gravitating lower. And inflation expectations are becoming un-tethered and shifting below inflation targets on a sustained basis, after an extended period where inflation has been below central bank targets.

The Fed’s inflation target

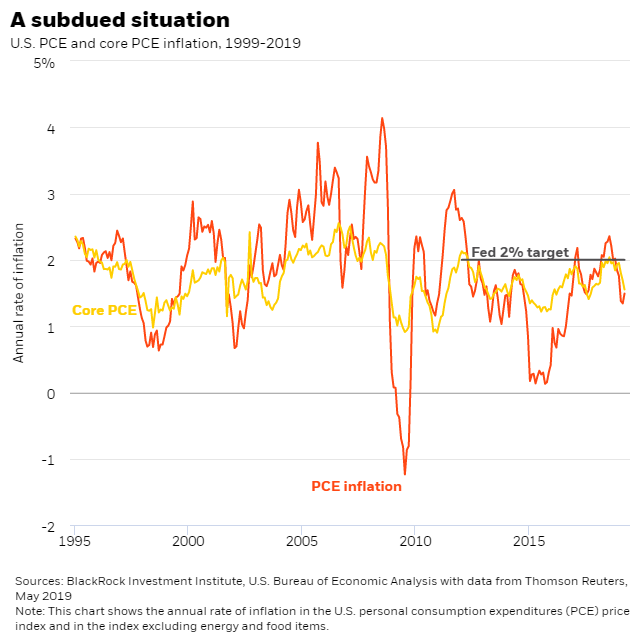

The Fed uses the personal consumption expenditures (PCE) price index for its inflation target, but the committee focuses on the core PCE index to remove the distraction of short-term volatility in food and energy prices. Both measures have consistently fallen below the 2% target since the global financial crisis. See the chart below.

The decline in inflation expectations is partly due to central banks struggling to hit their inflation targets in the post-crisis recovery, amid slow wage growth and recent soft commodity prices.

Falling interest rates and inflation expectations reduce the distance between the actual interest rate and the effective lower bound (ELB)–the minimum level of interest rates that the central bank can feasibly set. The negative policy rates in Japan and the euro-zone, for example, show that this level can be below zero. Interest rates below zero could harm the profit model of the banking sector and even lead to depositors – who may have to pay the bank to hold their money–withdrawing their money from the system.

Projections by the Fed (Roberts and Kiley 2017) suggest that the ELB could become a constraint for U.S. monetary policy for around one third of the time–a risk that had been very small prior to the Great Recession. Once the ELB is reached, the Fed cannot reduce interest rates any further in a recession. This means unconventional policies – such as quantitative easing (QE)–would again become the second-best instruments of choice. Then, the inability to cut rates further could lower inflation expectations again, potentially shrinking monetary manoeuvring room even more. There is an obvious desire to avoid the deflation spiral and liquidity trap problems seen in the Great Depression–or in Japan.

Toward make-up strategies

The Fed’s possible policy shift could be from the flexible inflation forecast targeting that the Fed and other developed market central banks currently follow toward “make-up” strategies. The latter explicitly require central banks to make up for past misses of their inflation target. These options are being discussed by the Fed, and other central banks – the Bank of Canada and Sweden’s Riksbank–have pondered similar changes in the past. The European Central Bank may also reassess its strategy after a leadership transition later this year.

Stay tuned for the next blog in this series, in which I will discuss the various monetary policy options the Fed is considering. And read more macro insights in our Macro and market perspectives.

Elga Bartsch, PhD, Head of Economic and Markets Research for the BlackRock Investment Institute, is a regular contributor to The Blog.

*****