by Kristina Hooper, Global Market Strategist, Invesco Ltd., Invesco Canada

An informal Invesco poll of North American institutional investors recently revealed that geopolitical risk was a top concern for 2019. And they’re not the only ones worried: European Central Bank President Mario Draghi recently noted that the risks to the downside have increased, blaming, among other things, “the persistence of uncertainties related to geopolitical factors and the threat of protectionism…” In his annual letter to investors in January 2019, Seth Klarman of Baupost warned of the threat of geopolitical disruption: “Social frictions remain a challenge for democracies around the world, and we wonder when investors might take more notice of this.”

I couldn’t agree more with these sentiments — I’ve been warning about the risks of geopolitical disruption for several years. However, not all disruption is created equal. My main concerns are those geopolitical risks that can directly impact economic growth. Largely, this means trade policy, but there are other risks that can impact economic growth as well. Below, I discuss the origins and implications of the geopolitical risks that I believe are material concerns for investors, with a focus on the twin forces of populism and nationalism.

Origins of today’s disruption

From WWII to the Cold War. Geopolitical disruption has been around for thousands of years. However, since World War II the developed world has enjoyed a long period of relative peace as countries settled into the notion of a new world order that pitted the US against the then-Soviet Union in a Cold War. In the ensuing years, institutions such as the United Nations and alliances such as NATO helped avert a number of geopolitical conflicts that could have become military actions, reinforcing this order.

The collapse of the Soviet Union. The end of the USSR led to a period of greater complexity in which the United States was widely perceived to be the dominant force in the world; that in turn ushered in a great period of globalization, helped by the World Trade Organization. Within the last decade, however, cracks have begun to appear in this order. Geopolitical tumult has increased over the last several years and has been a powerful force since then.

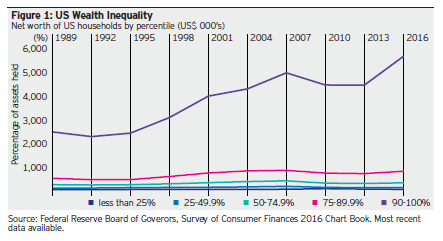

The post-GFC wealth divide. This tumult was borne, at least partially, of the way in which developed countries combated the Global Financial Crisis – largely through monetary policy stimulus rather than fiscal stimulus. This didn’t directly stimulate the economy – hence for years it was a very weak recovery – but instead caused asset inflation, primarily for stocks. This greatly exacerbated the wealth inequality gap — those with assets saw their financial situation improve; those without were left behind. Historically, we have seen that a widening wealth inequality gap often leads to some level of civil discontent. In addition, a substantial increase in immigration in a relatively short period of time has also been a catalyst for discontent and unrest, and it is certainly a contributing factor to the current political instability we are seeing in various countries.

Discontent has led to a rise in populism and nationalism

Today, much of the civil discontent has manifested itself in populist, nationalist movements that have focused on the perceived damage created by globalization. These movements have appeared around the world, and they transcend the right-wing/left-wing divide.

What is populism? Populism is very difficult to define. It has been described as “a thin-centered ideology”1, and as a set of loose generalizations that can be characterized by “an antagonism between the people and the elite, as well as the primacy of popular sovereignty, whereby the virtuous general will is placed in opposition to the moral corruption of elite actors.”2 The Encyclopedia Britannica defines populism more succinctly as a political program or movement that champions the common person, usually by favorable contrast with an elite.” Simply put, “populism worships the people”3, and so it is naturally a rejection of the status quo, and a rejection of expertise.

What is nationalism? Nationalism is defined by the Oxford Dictionary as “identification with one’s own nation and support for its interests, especially to the exclusion or detriment of the interests of other nations.” And so nationalization, by its very nature, is likely to be anti-globalization.

Populism + nationalism. Although not always the case, populism and nationalism can go hand in hand, as we have seen in the last few years. Populist, nationalist movements have spread to numerous countries.

- In the 2016 US presidential election, two candidates (Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump) were labeled as populists, with one (Trump) also labeled a nationalist.

- The Brexit campaign led by the UK Independence Party (UKIP) in 2016 was a populist, nationalist movement.

- The Philippines has a very popular right-wing nationalist populist leader, Rodrigo Duterte, who was elected in 2016.

- In 2018, right-wing nationalist populist Jair Bolsonaro was elected in Brazil.

- Italy is in the unique position of being led by a coalition government that is one part right-wing populist and one part left-wing populist. This has placed its finances in a precarious position, given the right-wing’s focus on cutting taxes and the left wing’s focus on increasing the government safety net, including basic income. This situation has led to an intense battle with the European Union on Italy’s fiscal responsibility requirements.

Nationalist, populist movements are abundant in Europe, as noted by Chancellor Angela Merkel, who recently explained, “Populism and nationalism are strengthening in all our countries.” Steve Bannon, the former chief strategist to US President Donald Trump and a self-described nationalist and populist, has noted its spread across continents: “the populist revolt now burns like a prairie fire from Europe to North America to South America.”

Three risks of the populist, nationalist movement

The twin trends of populism and nationalism can be dangerous for three main reasons: 1) the negative impact on economic growth caused by de-globalization; 2) the de-stabilization of institutions, and 3) the rejection of expertise.

1. The risks of de-globalization on economic growth

We are currently experiencing a trend of growing “economic nationalism” — also known as protectionism — which is threatening the future of key trade agreements and has resulted in a very substantial tariff war with China, as well as the potential for tariff wars with other countries.

It is important to note that protectionism usually does not occur in isolation, but can have a domino effect that results in a significant negative impact on global economic growth. A case in point is the Great Depression. The compounding effect of protectionist policies in the 1930s was documented by Barry Eichengreen and Douglas Irwin in The Journal of Economic History:

“The Great Depression of the 1930s was marked by a severe outbreak of protectionist trade policies. Governments around the world imposed tariffs, import quotas, and exchange controls to restrict spending on foreign goods. These trade barriers contributed to a sharp contraction in world trade in the early 1930s beyond the economic collapse itself, and to a lackluster rebound in trade later in the decade, despite the worldwide economic recovery.”

The results of protectionism in the 1930s were dramatic: world trade volume fell 16% from the third quarter of 1931 to the third quarter of 1932. And between 1929 and 1932 it fell 25% with and almost half of this drop attributed to higher tariff and nontariff barriers.4 The current global economic slowdown suggests that protectionism is again wreaking damage on the global economy — and it could be more dramatic today given the potential for supply chain disruption. In the wake of Apple’s downward earnings guidance several weeks ago, in which it partially blamed China for lower demand, the chairman of the White House’s Council of Economic Advisers warned that “a heck of a lot of US companies that have sales in China…are going to be watching their earnings being downgraded next year until we get a deal with China.”

2. The de-stabilization of institutions

NATO, the European Union, the United Nations and the World Trade Organization all have, to varying degrees, been destabilized by populist, nationalist movements. The European Union in particular has come under attack from such movements across the European continent.

- The United Kingdom’s nationalist UKIP party was able led the movement to leave the European Union, which ultimately resulted in the successful Brexit vote.

- France’s populist “yellow vest” movement, which began last fall in protest of a climate change-related gasoline tax, has shown no signs of abating in early 2019 and has been negatively impacting French economic growth.

- Germany’s nationalist movements, reacting to a high level of immigration from war-torn countries in the Middle East, have undermined Chancellor Angela Merkel’s leadership and caused her to moderate immigration plans.

- Poland has seen the rise of its own nationalist party, the Law and Justice Party, which is defying the European Union’s authority on issues such as judicial appointments.

Challenges to the world order are also creating uncertainty in Asia, where South Korea and Japan are becoming increasingly worried that they will not be able to rely on the US to ensure their safety. This has caused Japan to pass legislation enabling it to provide for its own defense and has caused South Korea to become more aligned with North Korea. The ramifications of these changes could be felt for decades to come, as China appears to be positioning itself as the protector of democracies in Asia.

NATO is also showing fragility, as the US continues to threaten to withdraw from the alliance. The populist coalition government in Italy — the third-largest economy in the European Union — has made overtures to Russia, which arguably undermines NATO.

In short, many of the longstanding alliances carefully assembled in the wake of World War II are tearing at the seams. Tensions at the recent G7 meeting underscore the greater issue of these shifting alliances, which I have worried about for nearly two years. By imposing tariffs on close allies — with the rationale of alleviating national security concerns — the US runs the risk of alienating those allies, which may prove problematic when foreign policy/security issues arise and their help is needed. Recall the enormous support the US enjoyed when it invaded Afghanistan following the 9/11 terrorist attacks; the United Kingdom rushed to support the US and sent troops to Afghanistan, later joined by Canada, Australia, Germany and others. It is also worth noting that in a November 2017 speech, UK Prime Minister Theresa May warned Russia that, “The UK will do what is necessary to protect ourselves, and work with our allies to do likewise.” If certain countries such as the US are viewed as having a friendlier relationship with Russia, they may not be made privy to all the information other members of the G7 share.

Often, disruption can be a positive — think of the positive outcomes that can result from creative destruction. However, in this case I worry that shifting political alliances are likely to be more negative than positive, with implications for issues from military actions to the fight against terrorism to cybersecurity. However, as with tariffs, the impact on those issues is hard to quantify because we don’t know how this will play out — there are so many possible outcomes at this juncture. However, we can’t ignore that the de-stabilization of these institutions can arguably jeopardize democratic institutions, which would be negative for economic growth.

One area that is easier to quantify is the impact on the World Trade Organization (WTO), which was created in 1996. Over the last several decades, lower tariffs and relaxed trade barriers strengthened global supply chains and fueled a major increase in global trade. In fact, the average rate of tariffs on imports by WTO members declined from slightly more than 12.74% in 1996 to 8.8% in 2016. Global trade went from $5 trillion in 1996 to $19 trillion in 2013.5 However, the US has bypassed the WTO in its recent trade disputes and has threatened to withdraw entirely. As the Cato Institute has made clear, the consequences of a withdrawal from the WTO would be “immense” and include “diminished trade growth, costly market and supply-chain disruptions, and the destruction of jobs and profits, especially in import- and export-dependent US industries.”6

3. Rejection of expertise

Populism, because of its aversion to elites, often results in a rejection of expertise. As explained by academic Kingsley Moghalu, “attempts to substitute facts and empirical foundations with conviction as a basis for public policy creates sub-optimal outcomes.”7 Academic Francesco Nicoli argued that “populism constitutes a form of rejection of specialization at its very best.”8 As an example, he cites “the isolation that the academics — and economists in particular — suffered during the Brexit debate: the simple fact of being “specialist” in something meant to be colluded with ‘the elites.”8

However, economic experts were correct about the significant economic slowdown the United Kingdom would experience if it pursued Brexit. This rejection of expertise is also chronicled in Michael Lewis’ recent book, “The Fifth Risk,” which explores the dangers of placing government agencies such as the US Department of Energy in the hands of non-experts. This can be not only problematic but downright dangerous, given that the Department of Energy is charged with ensuring the safety of the electrical grid, supporting early stage innovation in the energy industry (which would be essentially non-existent without government support), storing radioactive waste and finding and collecting nuclear materials that could be utilized as weapons.

The environment is just one area where a rejection of expert views can have a calamitous effect. For example, the National Climate Assessment, a legally mandated climate report compiled from a variety of scientists and government agencies, presented a dire warning on the negative effects of climate change including hundreds of billions in economic costs, crop failures in the Midwest and the spread of wildfires to the Southeast. The report estimated that the cost to the US economy will be more than $500 billion a year in extreme weather damages and lost labor and crop damage by the end of this century.9 While that is decades away, economies are already experiencing damage from extreme weather episodes related to climate change.

Central banks to the rescue

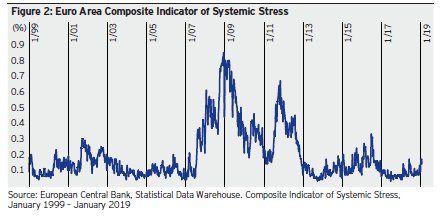

In the face of the more immediate geopolitical risks, one source of stability can be supportive central banks. For example, European Central Bank (ECB) President Mario Draghi, whose term began in November 2011, was thrown into the midst of a geopolitical calamity — the Greek debt crisis. However, he quickly made it clear that the ECB would be very supportive, indicating this in his famous “whatever it takes” speech that calmed markets and sent systemic stress down.

Systemic stress has stayed relatively low since then despite a series of tumultuous geopolitical events such as Brexit as well as last year’s Italian elections and the ensuing wrangling over Italy’s budget. Much of that can be attributed to Draghi’s influence —markets have confidence that he means what he says, and that he will continue to provide as much monetary support as necessary. Similarly, the Federal Reserve has served as a stabilizing, reassuring force. In September 2011, a month after US government credit was downgraded by Standard & Poor’s in the wake of government dysfunction, Fed Chair Ben Bernanke reassured that, “The Federal Reserve will do all it can to help restore high rates of growth and employment in a context of price stability.” The Federal Reserve’s promise to be supportive helped stabilize markets and indicated to market participants that it was the fourth — and far more stable — branch of government; stocks move higher in ensuing months.

Conclusion

Geopolitical disruption is nothing new and, in general, should not impact stocks over the longer term. Of course, in the short term the stock market is a voting machine, which means geopolitical disruption can cause volatility and impact stock price movements and credit spreads. In addition, recent geopolitical developments have resulted in serious risks that can directly impact economic growth — I’m largely referring to trade policy, although some other risks, such as the rejection of expertise, can impact economic growth as well. These are the material geopolitical risks that should matter to investors. The good news is that supportive central banks have historically served at times as a source of stability in the face of geopolitical instabi

This post was originally published at Invesco Canada Blog

Copyright © Invesco Canada Blog