by Michael Lebowitz, 720 Global Research

Since the U.S. economic recovery from the 2008 financial crisis, institutional economists began each subsequent year outlining their well-paid view of how things will transpire over the course of the coming 12-months. Like a broken record, they have continually over-estimated expectations for growth, inflation, consumer spending and capital expenditures. Their optimistic biases were based on the eventual success of the Federal Reserve’s (Fed) plan to restart the economy by encouraging the assumption of more debt by consumers and corporations alike.

But in 2017, something important changed. For the first time since the financial crisis, there will be a new administration in power directing public policy, and the new regime could not be more different from the one that just departed. This is important because of the ubiquitous influence of politics.

The anxiety and uncertainties of those first few years following the worst recession since the Great Depression gradually gave way to an uncomfortable stability. The anxieties of losing jobs and homes subsided but yielded to the frustration of always remaining a step or two behind prosperity. While job prospects slowly improved, wages did not. Business did not boom as is normally the case within a few quarters of a recovery, and the cost of education and health care stole what little ground most Americans thought they were making. Politics was at work in ways with which many were pleased, but many more were not. If that were not the case, then Donald Trump probably would not be the 45th President of the United States.

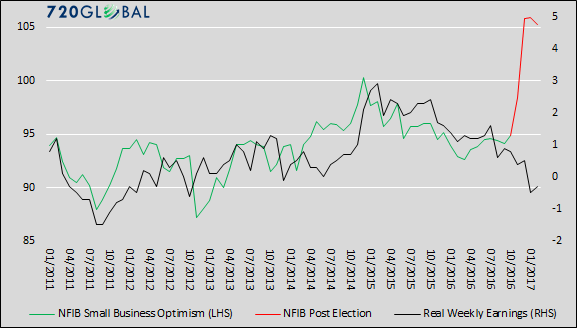

Within hours of Donald Trump’s victory, U.S. markets began to anticipate, for the first time since the financial crisis, an escape hatch out of financial repression and regulatory oppression. As shown below, an element of economic and financial optimism that had been missing since at least 2008 began to re-emerge.

Data Courtesy: Bloomberg

What the Federal Reserve (Fed) struggled to manufacture in eight years of extraordinary monetary policy actions, the election of Donald Trump accomplished quite literally overnight. Expectations for a dramatic change in public policy under a new administration radically improved sentiment. Whether or not these changes are durable will depend upon the economy’s ability to match expectations.

Often Wrong, Never in Doubt

The institutional economists searching for a coherent outlook for 2017 are now faced with a fresh task. President Trump and his cabinet represent a significant departure from what has come to be known as “business-as-usual” Washington politics over the past 25 years. Furthermore, it has been 89 years since Republicans held control of the White House as well as both the House of Representatives and the Senate. The confluence of these factors suggests that the outlook for 2017 – policy, the economy, markets, geopolitical risks – are highly uncertain. Despite what appears to be an inflection point of radical change, most of which remains unknown, the consensus opinion of professional economists and markets, in general, are well-aligned, optimistic and seemingly convinced about how the economy and markets will evolve throughout the year. The consensus forecast based upon an assessment of economic projections from major financial institutions appears to be the result of a Ph.D. echo chamber, not rigorous independent analysis.

Economic Outlook – Consensus Summary

After a thorough review of several major financial institutions’ economic outlooks for 2017 and market implied indicators for the year, below is an overview of what 720 Global deems to be the current consensus outlook for 2017.

- The consensus is optimistic about economic growth for the coming year with expectations for real GDP growth in the 2.0-2.5% range

- Recession risks will remain benign

- The labor market is now at or near full employment

- Wage growth is expected to increase to the 3.0-3.5% level as is customary for the economy at full employment

- Inflation is expected to reach and exceed the Fed’s 2.0% target level

- The Fed is expected to raise the Federal Funds rate in 25 basis point increments two or three times in 2017

- The Fed will maintain the existing size of its balance sheet

- Some form of fiscal stimulus will occur by the second half of the year

- Fiscal stimulus is expected to be modest and unlikely to have a big impact on fiscal deficits

- Tax reform will occur by the second half of the year and is viewed as highly supportive of corporate profits

- Regulatory reform will begin to take shape in the first half of the year

- Trade will be affected by some form of border tax adjustment, the economic impact of which is expected to be low

- The combination of fiscal stimulus, tax reform, and regulatory reform in conjunction with an economy that is growing above trend and at full employment easily offsets Fed rate hikes supporting the optimistic outlook for economic growth

Despite the low probability of accuracy, the consensus outlook for 2017 is the starting point from which a discussion should begin because it is reflective of what markets and investors expect to transpire. Markets are pricing to this set of outcomes for the year.

Deviations

Having established a consensus baseline, further attention is then paid to those areas where the consensus may indeed be wrong. Will inflation finally exceed the 2.0% level as expected? Will growth for the year end in the range of 2.0-2.5%? Can the new administration negotiate a fiscal stimulus package this year? These and many others are important questions that will dictate the strength of the U.S. dollar, the level of interest rates and the ability of equity markets to sustain current valuations.

If economic growth for the year is stronger than current projections and inflation is higher than forecast, then the Fed will appear to be behind the curve in hiking interest rates. In this circumstance, the Fed may begin to telegraph more than three rate hikes for the current year and a higher trajectory for rates in 2018. The interest rate markets will likely front run growth expectations and push interest rates higher. Given that investors have so little coupon income to protect them from price changes, such a move could occur in a disorderly manner, which will tighten financial conditions and choke off economic growth.

If, on the other hand, economic growth for the year falters and continues the recent string of disappointing, sub-2.0% readings, then fears of recession, and likely an abrupt change in confidence, will re-emerge.

This exercise undertaken each year by economists is akin to a meteorologist’s efforts to predict the weather several weeks in advance. The convergence of high and low-pressure systems will produce a well-defined outcome, but there is no way to ascertain weeks or even days in advance that those air masses will converge at a precise time and location, or that they will converge at all. It does in fact, as they say, very much depend on the “whether.” Whether consumers borrow and spend more, whether companies hire and pay more or even whether or not confidence in a new administration promising a variety of pro-growth policies can fulfill those in some form.

The Lowest Common Denominator

Interest rates have already risen in anticipation of the consensus view coming to fruition. Although higher interest rates today are reflective of an optimistic outlook for growth and inflation, the economy has become dependent upon low rates. Everything from housing and auto sales to corporate buybacks and equity valuations are highly dependent upon an environment of persistently low interest rates. So, when the consensus overview expects higher interest rates as a result of higher wage growth and inflation, it is difficult to reconcile those expectations with the consensus path for economic growth.

Investors and markets continue to give the hoped-for outcome the benefit of the doubt, but that outcome seems quite inconsistent with economic reality. That outcome is that policy will promote growth, growth will advance inflation and interest rates must therefore rise. The problem for the U.S. economy is that the large overhang of debt is the lowest common denominator. The economy is a slave to the master of debt, which must be serviced and repaid. The debt problem is largely the result of 35 years of falling interest rates and the undisciplined habits and muscle memory that goes with such a dominating streak. Marry that dynamic with the fact that this ultra-low interest rate regime itself has been in place for a full eight years, and the economy seems conditioned for an allergic reaction to rising rates.

Episodes of rising interest rates since the 1980’s, although short-lived, always brought about some form of financial distress. This time will likely be no different because the Fed’s zero-interest rate policy and quantitative easing have sealed the total dependency of the economy on consumption and debt growth. Regaining the discipline of a healthy, organic economic system would mean both a rejection of policies used over the last 30 years and intense public sacrifice.

Summary

Given the altar at which current day politicians’ worship – that of power, influence, and self-promotion – it seems unlikely that this new Congress and President are inclined to make the difficult choices that might ultimately set the U.S. economy back on a path of healthy, self-sustaining growth. Rather, debt and deficits will grow, and the enthusiasm around overly-optimistic economic forecasts and temporal improvements in economic output will fade as has been the case in so many years past. Although a new political regime is in store and it brings hope for a new path forward, the echo chamber reinforcing bad policy, fiscal and monetary, seems likely to persist.

Copyright © 720 Global Research