Human Capital in Portfolio Design: How to Help Young Investors

by Commonwealth Financial Network

Young investors are often undereducated when it comes to investing and accumulating sufficient assets for retirement. As industries move from defined-benefit structures to defined-contribution frameworks, this problem is only intensifying. Now, more than ever, young investors hold the keys to their own financial futures—and it’s your job to help your millennial clients meet their financial goals.

Young investors are often undereducated when it comes to investing and accumulating sufficient assets for retirement. As industries move from defined-benefit structures to defined-contribution frameworks, this problem is only intensifying. Now, more than ever, young investors hold the keys to their own financial futures—and it’s your job to help your millennial clients meet their financial goals.

Here, I’ll address various ways to help young investors, including the use of human capital in portfolio design.

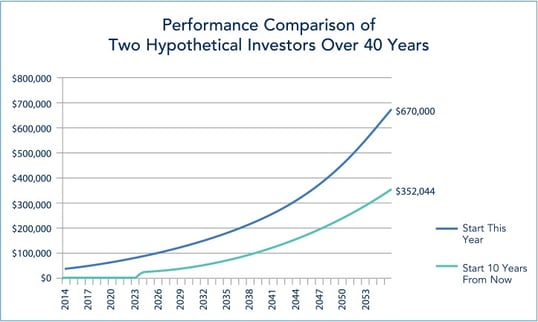

Many of you would likely agree that a longer time horizon allows investments to grow due to the effect of compounding. Let’s look at a hypothetical example.

Example: Two young clients begin with $20,000 up front, and both contribute $3,000 per year to their portfolios until retirement. Client A starts investing this year, while Client B waits 10 years before starting to invest.

Client A should end up with $30,000 (i.e., $3,000 x 10 years) more in the bank at retirement than Client B, right? But that doesn’t take compounding into account. Suppose both clients’ investments grow at a 6-percent rate. Because of compounding, after 40 years, Client A will end up with nearly double the assets of Client B, simply because she started saving and investing earlier (see chart below).

This exponential growth of investable assets will also benefit your business, as you’ll likely see an increase in fee-based revenues as the accounts grow. Plus, since the longevity and growth potential of younger clients’ assets tend to be higher, this could be of benefit if or when you decide to sell the business.

Many novice investors engage in “mental accounting,” artificially designating certain assets for specific purposes while not assessing their financial situation from a holistic perspective.

Specifically, mental accounting disproportionately affects young investors in terms of student loan debt and credit card debt. Commonly, young people contribute a significant portion of income to their 401(k)s, IRAs, or traditional brokerage accounts and delay paying down high-interest-rate credit card and student loans. But paying off student loans should be considered a top priority for these reasons:

- Student loan interest can be viewed as a risk-free investment, similar to a U.S. Treasury bond. Assuming the 30-year Treasury yields less than 4 percent, young investors are essentially saving themselves double the interest rate of a Treasury by paying off an 8-percent interest loan.

- Most student loans behave according to an amortization schedule, which means that interest is front-loaded. By paying down principal early, young investors can save thousands or even tens of thousands of dollars in interest over the life of the loan.

There are, of course, exceptions. If a company offers its employees a 401(k) matching program, for example, a young investor might be wise to take the opportunity to contribute up to the highest level matched by the company.

Once you have reviewed a young investor’s financial situation from a holistic perspective, he or she can then consider bucketing assets (i.e., designating assets for specific purposes). For example, a young investor might keep most of her taxable assets in high-quality, low-duration bonds, anticipating the purchase of a home over the next year or two. At the same time, you may decide with the client to invest qualified assets very aggressively, having earmarked them for retirement.

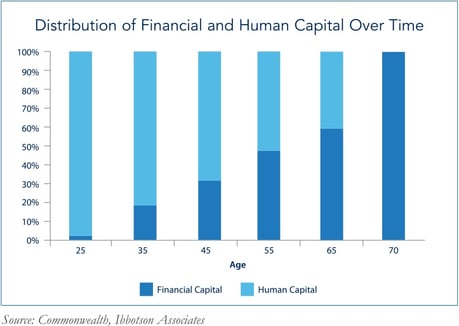

Human capital—the present value of all expected future labor income—is a somewhat new concept but arguably among the most important components of portfolio design, especially for younger generations. Of course, individuals also have financial capital, which includes investable assets such as stocks, bonds, and real estate. But for young investors, human capital is generally the largest piece of the pie because they have a long horizon of earnings ahead and very little financial capital to invest.

For example, an average 25-year-old investor with a $50,000 salary growing at 2 percent per year and $10,000 in current investments will have a distribution of human and financial capital similar to the one illustrated below:

As you can see, as the investor progresses through the earnings cycle, the proportion of financial capital to human capital grows through the power of compounding and additional contributions. Upon retirement (age 70 in the chart), financial capital is the largest portion of total wealth because, at that point, human capital diminishes significantly or ceases altogether. So, what does this mean for asset allocation?

Asset allocation decisions. For the purposes of asset allocation, think of human capital as a fixed income instrument. It generally consists of future payments that can be discounted back to the present to determine the value of the theoretical “security.”

According to Ibbotson Associates, if investors omit the labor income component when formulating their asset allocation decisions, they will ultimately end up with suboptimal asset mixes. As a result, it is advised that investors use a human capital portfolio (100-percent bond), in addition to a financial capital portfolio, when making strategic allocation decisions. The combination of human capital and financial capital would equal the client’s total wealth.

Life cycles and characteristics should play an important role in how investors view the human capital portion of their total wealth. For instance:

- Investors with safe labor income may want to invest more of their financial portfolio in equities.

- Investors with more volatile income patterns (e.g., at-will employees) may want to use a more conservative allocation.

- Investors whose labor income is highly correlated to equity markets may want to consider reducing their exposure to risk assets in their financial portfolios.

- Investors with a higher flexibility around labor income may want to increase their equity allocation.

Let’s take another look at that 25-year-old investor. He has a stable income stream that is noncorrelated to equities, so the financial portfolio for this individual would generally be allocated entirely to stocks. In this case, the total wealth portfolio would be approximately 4-percent equities and 96-percent bonds (human capital). On the other hand, if the 25-year-old had a highly volatile income stream correlated to equities, then the financial portfolio should have a preference for bond-like securities because the human capital portion of total wealth would exhibit equity-like characteristics.

Key takeaways. When using the human capital component in formulating asset allocation decisions, be sure to consider these main themes:

- Financial capital portfolios should be diversified to balance out the human capital portfolio.

- An investor whose human capital is highly correlated to risk markets should reduce the allocation to equities in the financial portfolio and increase exposures to bond-like instruments.

- Labor income flexibility and stability in cash flows should result in increased exposures to equities; however, the allocation to equities should decrease as an individual approaches retirement.

- Unlike bonds, human capital is illiquid, so investors may still wish to keep a portion of their investable assets in more conservative investments as a safety net.

Because much of their potential net worth is tied up in human capital, young investors often do not receive the same level of attention from financial advisors as their more senior counterparts. But the assets of young clients grow more quickly, and the business they can give to you has more longevity. In addition, young investors can be a key to winning new referrals or retaining the business of older relatives. By addressing the issues of these new investors early, you have the opportunity to build solid, long-term relationships whose returns will compound over time.

What other major issues are there for young investors? Do you use human capital in formulating asset allocation decisions? Please share your thoughts with us below.

This material is intended for informational/educational purposes only and should not be construed as investment advice, a solicitation, or a recommendation to buy or sell any security or investment product. Investors should contact their financial professional for more information specific to their situation.

All examples are hypothetical and are for illustrative purposes only. No specific investments were used. Actual results will vary.

Asset allocation programs do not assure a profit or protect against loss in declining markets. No program can guarantee that any objective or goal will be achieved. Investments are subject to risk, including the loss of principal. Because investment return and principal value fluctuate, shares may be worth more or less than their original value. Some investments are not suitable for all investors, and there is no guarantee that any investing goal will be met. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

Commonwealth Financial Network is the nation’s largest privately held independent broker/dealer-RIA. This post originally appeared on Commonwealth Independent Advisor, the firm’s corporate blog.

Copyright © Commonwealth Financial Network