by Sammy Suzuki, AllianceBernstein

For more than a decade, Brazil, Russia, India and China have dominated the landscape in emerging markets. But as the BRICs-driven commodities boom wanes, investors may need to rethink their approach.

Commodities demand has been the fuel for explosive emerging-markets growth since the BRICs era began in 2001. At that time, China joined the World Trade Organization and launched land reforms that triggered a vast building reconstruction boom in the world’s most populous nation. China’s insatiable appetite for commodities benefited Russia and Brazil, while India was widely seen as the next big thing.

Soaring commodities drove economic growth and some key countries also enjoyed a private credit boom as their currencies and inflation stabilized. For example, in Brazil, private credit as a percentage of GDP doubled to about 60% by 2011 from about 30% in 2005.

With commodity prices falling sharply in recent months as China’s growth slows, the forces that have driven emerging-market growth—and outsized stock returns—have been thrown into question. Perhaps emerging markets have lost their luster, and investors will need to refocus their quest for higher returns elsewhere?

We don’t think so. In our view, there are still big opportunities in emerging-market equities—but things have definitely changed. The key is to understand how emerging markets have evolved and which countries and companies are more likely to thrive in an environment of lower commodity demand, moderating credit and shifting currency dynamics. Key areas to watch include:

- Commodity importers—lower prices might hurt commodity producing countries but importers should benefit. These include the Philippines, the Czech Republic, India, Korea, Thailand and Turkey.

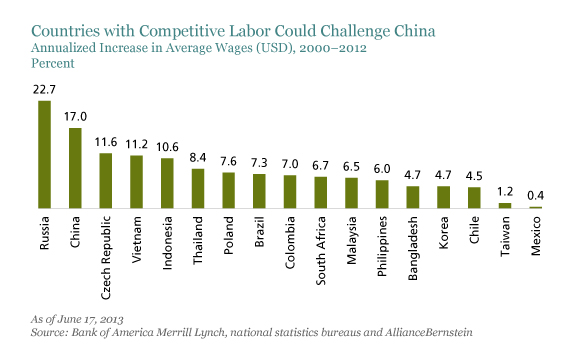

- Competitive labor—countries that can grab market share from China, as its labor rates rise, should do well. Vietnam, Bangladesh and Mexico have improved their relative competitiveness versus China in recent years by containing labor costs (Display below).

- Currency beneficiaries—weakening currencies are good for exporters. So a regional jetmaker in Brazil or a software house in Russia may enjoy a new catalyst for sales growth. Import substitution is another effect. For example, a domestic apparel–maker in South Africa could lower its prices versus importers, possibly taking market share from global giants like Levi’s and Zara.

- Crossover opportunities—small, innovative companies with access to the global supply chain can succeed in ways that would have been impossible a decade or two ago. For example, a company based in an emerging market, with production in a frontier market like Vietnam or Cambodia, that sells products in developed markets could do especially well by capturing the best of both worlds.

- Developed winners—large, developed-market companies with sales in emerging markets might also cash in on competitive advantages. Think about a dominant global toothpaste brand that could win big as its product proliferates in fast-growing markets.

Of course, the end of the commodity boom will be a sea change for emerging-market companies. In the past, they could throw capital at low-return projects and get bailed out by unrelenting economic growth. Those days are gone.

Without the enormous macroeconomic tailwinds they enjoyed, hidden weaknesses will suddenly become more visible in many companies. As a result, investors will need to scrutinize emerging-market countries and companies more thoroughly than ever. But, by focusing on good stewards of capital with solid business dynamics and profitability prospects, we think investors will find that there is definitely life after BRICs in emerging markets.

The views expressed herein do not constitute research, investment advice or trade recommendations and do not necessarily represent the views of all AllianceBernstein portfolio-management teams.

Sammy Suzuki is Portfolio Manager—Emerging Markets Core Equities and Director of Research—Emerging Markets Value Equities at AllianceBernstein.

Copyright © AllianceBernstein