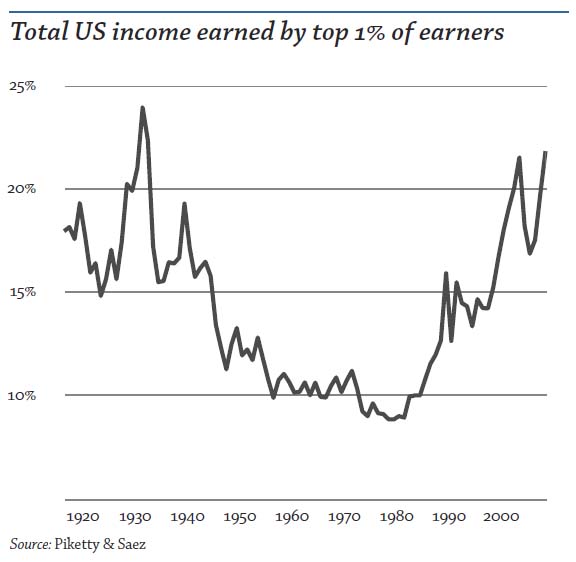

Besides this redistribution of wealth towards the financial sector was a redistribution to those who were already asset-rich. Asset prices were inflated by cheap credit and the assets themselves could be used as collateral for it. The following chart suggests the size of this transfer from poor to rich might have been quite meaningful, with the top 1% of earners taking the biggest a share of the pie since the last great credit inflation, that of the 1920s.

Who paid? Those with no access to credit, those with no assets, or those who bought assets late in the asset inflations and which now nurse the problem balance sheets. They all paid. Worse still, future generations were victims too, since one way or another they’re on the hook for it.

So with their crackpot monetary ideas, central banks have been robbing Peter to pay Paul without knowing which one was which. And a problem here is this thing behavioral psychologists call self-attribution bias. It describes how when good things happen to people they think it’s because of something they did, but when bad things happen to them they think it’s because of something someone else did. So although Peter doesn’t know why he’s suddenly poor, he knows it must be someone else’s fault. He also sees that Paul seems to be doing OK. So being human, he makes the obvious connection: it’s all Paul and people like Paul’s fault.

But Paul has a different way of looking at it. Also being human, he assumes he’s doing OK because he’s doing something right. He doesn’t know what the problem is other than Peter’s bad attitude. Needless to say, he resents Peter for his bad attitude. So now Peter and Paul don’t trust each other. And this what happens when you play games with society’s bonding.

When we look around we can’t help feeling something similar is happening. The 99% blame the 1%; the 1% blame the 47%. In the aftermath of the Eurozone’s own credit bubbles, the Germans blame the Greeks. The Greeks round on the foreigners. The Catalans blame the Castilians. And as 25% of the Italian electorate vote for a professional comedian whose party slogan “vaff a” means roughly “f**k off ” (to everything it seems, including the common currency), the Germans are repatriating their gold from New York and Paris. Meanwhile in China, that centrally planned mother of all credit inflations, popular anger is being directed at Japan, and this is before its own credit bubble chapter has fully played out. (The rising risk of war is something we are increasingly worried about…) Of course, everyone blames the bankers (“those to whom the system brings windfalls… become ‘profiteers’ who are the object of the hatred”).

But what does it mean for the owner of capital? If our thinking is correct, the solution would be less monetary experimentation. Yet we are likely to see more. Bernanke has monetized about a half of the federally guaranteed debt issued since 2009 (see chart below). The incoming Bank of England governor thinks the UK’s problem hasn’t been too much monetary experimentation but too little, and likes the idea of actively targeting nominal GDP. The PM in Tokyo thinks his country’s every ill is a lack of inflation, and his new guy at the Bank of Japan is revving up its printing presses to buy government bonds, corporate bonds and ETFs. China’s shadow banking credit bubble meanwhile continues to inflate…

For all we know there might be another round of illusory prosperity before our worst fears are realised. With any luck, our worst fears never will be. But if the overdose of monetary medicine made us ill, we don’t understand how more of the same medicine will make us better.

We do know that the financial market analogue to trust is yield. The less trustful lenders are of borrowers, the higher the yield they demand to compensate. But interest rates, or what’s left of them, are at historic lows. In other words, there is a glaring disconnect between the distrust central banks are fostering in the real world and the unprecedented trust lenders are signaling to borrowers in the financial world. Of course, there is no such thing as “risk-free” in the real world. Holders of UK cash have seen a cumulative real loss of around 10% since the crash of 2008. Holders of US cash haven’t done much better.

If we were to hope to find safety by lending to what many consider to be an excellent credit, Microsoft, by buying its bonds, we’d have to lend to them until 2021 to earn a gross return roughly the same as the current rate of US inflation. But then we’d have to pay taxes on the coupons. And we’d have to worry about whether or not the rate of inflation was going to rise meaningfully from here, because the 2021 maturity date is eight years away and eight years is a long time. And then we’d have to worry about where our bonds were held, and whether or not they were being lent out by our custodian. And of course, this would all be before we’d worried about whether Microsoft’s business was likely to remain safe over an eight year horizon.

We are happy to watch others play that game. There are some outstanding businesses and individuals with whom we are happy to invest. In an ideal world we would have neither Peters nor Pauls. In the imperfect one in which we live, we have to settle for trying hard to avoid the Pauls, who we fear mistake entrepreneurial competence for proximity to the money well. But when we find the real thing, the timeless ingenuity of the honest entrepreneurs, the modest craftsmen and craftswomen who humbly seek to improve the lot of their customers through their own enterprise, we find inspiration too, for as investors we try to model our own practice on theirs. It is no secret that our quest is to find scarcity.

But the scarce substance we prize above all else is trustworthiness. Aware that we worry too much in a world growing more wary and distrustful, it is here we place an increasing premium, here that we seek refuge from financial folly and here that we expect the next bull market.