by William R. Benz, PIMCO

- For investors, the biggest challenge now is moving from a world of normal distributions, with expected occurrences around the mean, to one of bi-modal distributions where more extreme scenarios prevail.

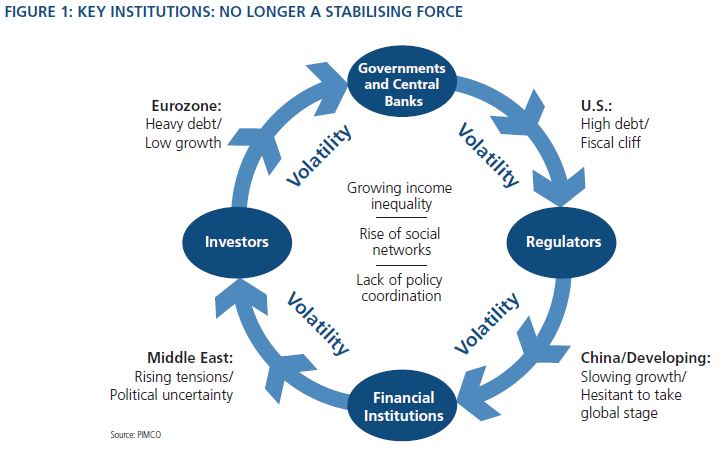

- Key institutions, including governments and central banks, were previously stabilising forces but are now helping to accelerate underlying, destabilising trends in the global economy and financial markets.

- In this environment, investors need to invest for outcomes rather than simply for beta and diversification.

Perhaps the most important tradition at PIMCO is our annual Secular Forum in May. Since I joined 26 years ago and participated in my first forum with 16 other investment professionals, our forums have become much bigger and much more global. More than 300 of us descended on Newport Beach or tuned in via video in our most recent round. But the tradition continues, as does the intensity and excitement, with the output of our forum – our three- to five-year secular outlook – forming the cornerstone of both our longer-term investment strategy and our business positioning.

Mohamed El-Erian, our CEO and co-CIO, in his Secular Outlook commentary "Policy Confusions & Inflection Points," summarized three themes that we expect to play out over the next few years: continued policy and political confusion, overly incremental public and private sector responses and, therefore, greater potential for inflection points. Mohamed also discussed the key investment implications of our outlook, noting that the strategies and guidelines that may have served investors in the past will likely be challenged in the context of inflection dynamics.

That point is worth revisiting and expanding upon because, in our view, investing is fundamentally changing. Previously, most investors simply aimed to beat their benchmarks and diversify among assets to mitigate risk. But today, as we face unusual uncertainty in the global economy and the financial markets, extreme events are not only possible but increasingly likely, and in this environment, we believe investors need to define their objectives and choose strategies that target specific outcomes.

Investors’ biggest challenge

The world is facing a number of very significant challenges for which there are no easy solutions. The eurozone faces high debt levels, a lack of structural growth and pressure to get the policy mix right to avoid contagion. The U.S. is suffering slow growth, high debt, a looming fiscal cliff and political polarisation. While enjoying higher relative growth, China and the developing world are also slowing and making difficult transitions from export-led to consumer-driven ‘emerged’ economies. And globally, a lack of policy coordination, increased income inequality and the growing use of social networks as communication tools also present long-term challenges.

Uncertainty is one common theme, and another is the potential for more extreme outcomes, good or bad. The eurozone, for instance, has to either find a path toward fiscal union or create a mechanism for orderly exit, with very little room to manoeuvre in between. Likewise, the U.S. needs to find a way to resolve its fiscal issues or face the consequences of a further downgrade and eventual loss of reserve currency status.

For investors, then, the biggest challenge is not continued volatility; that’s almost a given. The challenge is moving from a world of normal distributions, with expected occurrences around the mean, to one of bi-modal distributions where more extreme scenarios prevail.

Key institutions: once stabilisers, now accelerants

In the old normal, key institutions acted as stabilisers: They generally behaved in a counter-cyclical fashion to help enforce reversion to the mean. For example, governments and central banks enacted policies to stimulate growth and prevent deflation during economic downturns and did the opposite in upturns. Regulators tended to de-regulate during tough times and tighten the rules during times of excess, while financial institutions decreased and increased lending as interest rates rose and fell.

Their actions, individually and collectively, helped bring economic growth and the markets back to normal, back to long-term averages, back to the mean. They weren’t necessarily coordinated, but they were generally effective and helped create the Great Moderation of steady growth, strong returns and relatively low volatility that we witnessed from the mid-to-late 1980s until the global financial crisis in 2008.

But today, these institutions are acting as accelerants. Governments in Europe, the U.S. and Japan are under pressure to pursue fiscal austerity rather than stimulate growth, exacerbating the downturn. Central banks are largely going their own way, after a well-coordinated response to the financial crisis, and in some cases, are resisting stimulative measures, which is slowing, if not preventing, the healing process. Regulators, adopting a ‘never again’ mentality, are creating blunt instruments to solve complex problems, leading to unintended consequences, particularly in the banking sector, at a time when more rather than less lending should be the recommended medicine. And banks, especially in the eurozone, have been severely impacted by their holdings of sovereign debt, which, in turn, has led to a vicious cycle of falling share prices, credit rating downgrades, asset sales, reduced lending, slowing local economies, worsening government balance sheets and ultimately, an acceleration of, rather than a counterbalance to, the crisis.

Finally, investors are also acting as accelerants. Individual investors have always been more momentum-driven but had little aggregate impact on markets in the past due to their small size, lack of timely and direct access to information and lack of coordinated activity. But as they’ve grown in size and sophistication, accessing real-time information through their defined contribution plans, global platforms, multi-national distributors, private banks and independent financial advisors, their impact has become much more pronounced. When risk sectors outperform, flows into those sectors tend to increase; when they underperform, flows tend to diminish. In both cases, underlying trends are reinforced.

What’s even more interesting is how the behaviour of institutional investors has changed. This began in 2000-01, after the technology bubble burst. The perfect storm of plunging equity markets and falling interest rates turned corporate and public pension plan surpluses into deficits and created big challenges for foundations, endowments and others seeking income and targeting specific absolute returns. The movement toward solution-based investing was born as investors began to shift toward liability-driven investing (LDI), absolute return, income seeking and other, more specific strategies. The momentum increased following Lehman’s bankruptcy and again in response to recent events in Europe. But with this shift has come a more activist (or re-activist) approach, as investors make larger and more frequent changes to overall strategy, tactical weightings, benchmarks and guidelines. Some still prefer to rebalance around their longer-term, normal policy targets, but as a group – and we see this globally across our client base – institutional investors have indeed become more active.

Governments, central banks, regulators, financial institutions and investors – each group is responding to the challenges they are facing in a logical and well-intentioned fashion. Yet in the current secular environment, we believe their actions are adding to, rather than smoothing, volatility. And instead of acting as stabilising forces, we believe they are actually helping to accelerate the underlying destabilising trends. (See figure below.)

Significant implications for investors

Global challenges combined with these market accelerants have created an environment of unusual uncertainty in which ‘muddle-through’ is a temporary state. We believe this has significant implications for investors, particularly those who are still investing simply for beta and diversification rather than for specific outcomes.

First and foremost, the new normal is here, and investors need to embrace it. We coined the phrase a few years ago to describe a multi-speed world on a bumpy journey of deleveraging, reregulation and eventual reflation. We can argue whether we’re still on the journey or we’ve arrived at the final (though still very bumpy) destination. But what’s clear is that what felt like a ‘new’ normal back then now just feels normal. Gone are the days of the Great Moderation, reversion to the mean and normal-shaped distributions, in our view; instead, continued (high) volatility, acceleration in trends and bi-modal outcomes have become the new norm. In an era when muddle-through is no longer a viable option – for Europe, the U.S. and potentially others – investors need to rethink their overall approach and brace for more extreme economic and market events.

Second, there is no free lunch. There never really was, but investors are facing even more difficult trade-offs today. If the objective is to enhance yield or upside potential through credit, high yield, emerging markets, equities or other risk sectors, the likely trade-offs in a bi-modal world are higher volatility and greater downside. If the goal instead is to own ‘safe haven’ assets for downside risk mitigation, such as U.S. Treasuries, U.K. gilts or German bunds, the trade-off is currently negative real yields. And if the need is to maximise liquidity through cash instruments, the payoff is truly negative real yields (with negative nominal yields on occasion). Even when seeking inflation protection, whether through inflation-linked bonds or hard assets – like gold, real estate and commodities – we believe the trade-offs in terms of real yields, volatility and downside risk are much less attractive in this environment.

Third, investors need to think differently with respect to allocations, benchmarks and guidelines. We’ve highlighted this in the past, but it’s even more important today. In our view, asset allocation should be risk-factor-based as bi-modal distributions and accelerants are not friendly toward traditional mean-variance methodologies, which aim to maximize returns for given levels of risk. Benchmarks should be GDP- rather than market value-weighted, particularly in fixed income space, to reduce exposure to those countries, sectors and issuers with the highest or fastest growing debt. And guidelines should be flexible, with more rather than less discretion, so as to allow managers to play both offence and defence in a bi-modal world.

Fourth, investors should be confident in their managers’ ability to understand and measure risk. Global challenges, market accelerants and unusual uncertainty put a premium on risk management. This includes understanding how the credit sensitivity of fixed income investments can affect their duration – i.e., ‘hard’ versus ‘soft’ duration – and help determine what is considered a ‘safe haven’ and what isn’t. It means performing credit analysis of sovereigns knowing they have more than just interest rate risk. It necessitates analysing the entire spectrum of the capital structure to pinpoint exact needs in terms of collateral, covenants and other forms of defence. Derivatives continue to be useful tools, but being able to identify and control counterparty risk is increasingly important. And leverage, while appropriate in certain circumstances, needs to be well understood. Bottom line: we believe in developing multiple risk measures and stress testing often.

Finally, investors need to develop specific objectives and invest for outcomes rather than simply for beta and diversification. Many investors traditionally started with risk/return targets and used historical mean-variance analysis as a framework to determine asset allocations across multiple asset classes, with benchmarks for each asset class and sub-category, and then found managers that aimed to provide returns above their benchmarks. In the days of normal-shaped distributions and reversion to the mean, this was a widely accepted strategy: Long-term realised returns and volatility came in largely as expected, and further diversification – across asset classes, within asset classes and across different managers and styles – helped to smooth short-term swings. It was a beta-driven strategy, aided by diversification. But the world has changed, and we believe investors need to deepen their understanding of their objectives and invest for outcomes.

Setting objectives and investing for outcomes

Every investor has a unique set of needs and circumstances that should form the basis for setting investment objectives. Yet it's important to consider the secular context as well, particularly given the challenges and trade-offs we're likely to face:

- Prolonged period of low real yields on high-quality assets, with negative real yields on traditional ‘safe havens’

- Increased potential for low and even negative real returns

- Continued high volatility with increased likelihood of bi-modal outcomes

- Eventual, though uneven, inflation pressures

Income-oriented investors should consider emphasizing high-quality fixed income spread sectors, such as covered bonds, mortgage- and asset-backed securities, investment grade credit and, depending on risk tolerance, upper-tier emerging market and high yield issues and higher dividend-paying equities.

Investors with specific return objectives should consider focusing more on absolute return strategies, ranging from unlevered LIBOR-plus approaches – essentially seeking to outperform cash – to alternative strategies, depending on their risk/return targets and liquidity needs. Credit, emerging markets, equities and other asset classes can also play roles, individually or grouped into a multi-asset approach, as long as risk factors and exposures are well understood and investors consider ways to potentially limit downside risk under more extreme ‘left tail’ scenarios.

Investors concerned with volatility and ‘fat tail’ events should consider risk-mitigating strategies. If investors want to defend against downside, potential strategies would include positions in hard-duration, ‘safe-haven’ assets, explicit tail-risk hedges or a combination. Investors focused on liabilities may want a liability-matching or LDI program. Alternatively, if the goal is to maximise liquidity, cash and short-term strategies would likely play a significant role.

Lastly, for investors worried about reflation, the suggested focus is on potential inflation hedges, such as inflation-linked bonds, commodities and real estate.

In truth, many investors will likely want to employ more than one approach – income with an inflation-hedging component, absolute return with tail-risk hedges, LDI programs that include a combination of derivative-based overlays with LIBOR-plus strategies on the underlying collateral, or any of these with a cash buffer that can be used for liquidity or to invest tactically if the opportunity arises. And this makes sense. In our view, as long as investors focus on their objectives and their targeted outcomes, rather than fall into the old ‘invest for beta and diversification’ trap, they can navigate a world of secular challenges, accelerants and unusual uncertainty.

Past performance is not a guarantee or a reliable indicator of future results. All investments contain risk and may lose value. Investing in the bond market is subject to certain risks including market, interest-rate, issuer, credit, and inflation risk. Covered bonds are generally affected by changing interest rates and credit spread; there is no guarantee that covered bonds will be free from counterparty default. High-yield, lower-rated, securities involve greater risk than higher-rated securities; portfolios that invest in them may be subject to greater levels of credit and liquidity risk than portfolios that do not. Mortgage and asset-backed securities may be sensitive to changes in interest rates, subject to early repayment risk, and their value may fluctuate in response to the market’s perception of issuer creditworthiness; while generally supported by some form of government or private guarantee there is no assurance that private guarantors will meet their obligations. Absolute return portfolios may not necessarily fully participate in strong (positive) market rallies. Investing in foreign denominated and/or domiciled securities may involve heightened risk due to currency fluctuations, and economic and political risks, which may be enhanced in emerging markets. Inflation-linked bonds (ILBs) issued by a government are fixed-income securities whose principal value is periodically adjusted according to the rate of inflation; ILBs decline in value when real interest rates rise. Certain U.S. Government securities are backed by the full faith of the government, obligations of U.S. Government agencies and authorities are supported by varying degrees but are generally not backed by the full faith of the U.S. Government; portfolios that invest in such securities are not guaranteed and will fluctuate in value. Equities may decline in value due to both real and perceived general market, economic, and industry conditions. Dividends are not guaranteed and are subject to change and/or elimination. The value of real estate and portfolios that invest in real estate may fluctuate due to: losses from casualty or condemnation, changes in local and general economic conditions, supply and demand, interest rates, property tax rates, regulatory limitations on rents, zoning laws, and operating expenses. Commodities contain heightened risk including market, political, regulatory, and natural conditions, and may not be suitable for all investors. Tail risk hedging may involve entering into financial derivatives that are expected to increase in value during the occurrence of tail events. Investing in a tail event instrument could lose all or a portion of its value even in a period of severe market stress. A tail event is unpredictable; therefore, investments in instruments tied to the occurrence of a tail event are speculative. Derivatives may involve certain costs and risks such as liquidity, interest rate, market, credit, management and the risk that a position could not be closed when most advantageous. Investing in derivatives could lose more than the amount invested. Diversification does not ensure against loss. There is no guarantee that these investment strategies will work under all market conditions or are suitable for all investors and each investor should evaluate their ability to invest long-term, especially during periods of downturn in the market.

LIBOR (London Interbank Offered Rate) is the rate banks charge each other for short-term Eurodollar loans. It is not possible to invest directly in an unmanaged index.

This material contains the opinions of the author but not necessarily those of PIMCO and such opinions are subject to change without notice. This material has been distributed for informational purposes only. Forecasts, estimates, and certain information contained herein are based upon proprietary research and should not be considered as investment advice or a recommendation of any particular security, strategy or investment product. Information contained herein has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, but not guaranteed. No part of this material may be reproduced in any form, or referred to in any other publication, without express written permission.

©2012, PIMCO.