by Thomas Fahey, Loomis Sayles

Those familiar symptoms are back again to start the summer: risk aversion; falling equity prices; rising volatility; record-low German and US government bond yields; wider credit spreads; a European country getting picked on; and a stronger US dollar. We have seen this bad movie twice before, during the summers of 2010 and 2011.

If this is indeed another rerun, we should expect central bank and other official policy responses to help limit the fallout. Markets seem to have become addicted to central bank liquidity injections and go through withdrawal when these boosters do not come in regular doses. Some market watchers are wondering whether the global financial system is caught in a liquidity trap—an environment in which short-term interest rates have reached zero and additional expansionary monetary policy cannot jumpstart real economic growth.

As we see it, hesitancy and solvency traps—not a liquidity trap—are the main obstacles to a lasting economic recovery. To escape these traps, combat uncertainty and ignite growth, we think policy makers must stabilize the financial system, commit to consistent, aggressive liquidity measures, and write off bad debts.

NOT A LIQUIDITY TRAP

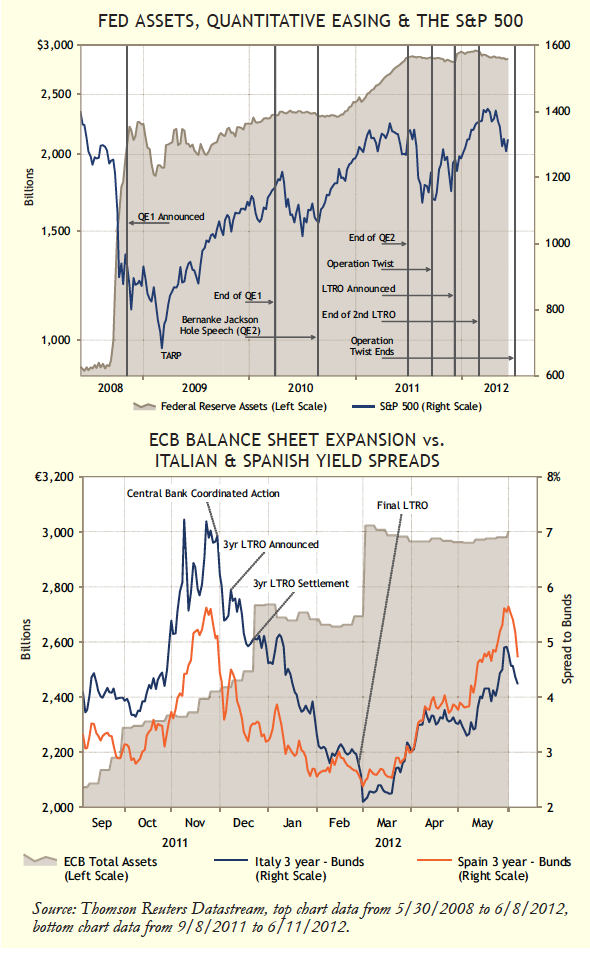

Over the past four years, each time a major Federal Reserve Board (Fed) or European Central Bank (ECB) liquidity expansion program has come to an end (QE1, QE2, Operation Twist, LTROs), markets have experienced a swoon, as shown in the charts at right. Some may argue that recurring bouts of liquidity withdrawal in the markets mean monetary policy does not work, and that we are ensnared in a Keynesian “pushing on a string” liquidity trap.1 In our opinion, accommodative monetary policies have shown some positive effects. The ECB’s longterm refinancing operation (LTRO) in the fourth quarter of 2011 was remarkable in breaking the fever of 1British economist John Maynard Keynes (1883-1946) asserted that although central banks can lower interest rates and increase the money supply, they cannot force banks to lend or businesses and consumers to borrow. Thus, during periods of heightened economic uncertainty, Keynes believed expansionary monetary policy efforts to increase the money supply were futile, akin to “pushing on string.”

risk aversion around European assets, even though the results wore off quickly. The Fed’s January 2012 announcement that it would not hike rates until late 2014—a commitment 18 months longer than previously stated—helped shape interest rate expectations and investor risk appetite. Risky assets had a strong first quarter with the central banks’ assistance.

Maybe it is just coincidental, but we believe the rearview mirror suggests a more constant reflation effort is necessary. Though central banks around the world have massively expanded their balance sheets, risk aversion continues to percolate throughout the markets. Yields on what many view as relative safe-haven bonds have been breaking all-time lows, the US dollar has been rallying, and commodity prices have been falling. Real yields on German and Swiss bonds have gone negative. Government bond yields of zero or less imply zero risk appetite—a sign that the system may need additional money and capital.

THE HESITANCY TRAP

If a Keynesian liquidity trap is not the issue, policy makers and the private sector may be stuck in a hesitancy trap. Policy makers are perhaps not bold enough to maintain constant, aggressive policy stances. We must not ignore the fact that central bank liquidity injections have a short half-life before the salve wears off and investor risk appetite fades. This fickle risk appetite and an uncertain private sector seem to be further complicating matters.

Policy makers are likely caught in a hesitancy trap for a number of reasons including: fear of runaway inflation from unconventional monetary policies; desire to discourage moral hazard policies after a major credit bubble; reluctance to recognize bad debts, raise bailout capital and dilute private shareholders; trepidation about the unknown; political challenges and complex decision-making processes; and the “hope” that the good old days of normal borrowing and spending behavior will simply return. Financial markets usually mete out heavy-handed discipline to hesitant policy makers, demanding sharply higher yields in exchange for their capital. We have seen this scenario play out over the past three years. Thus far, the short-term nature of policy responses has not instilled markets with lasting calm, and yield spreads have fluctuated as a result.

The private sector appears to be in its own hesitancy trap, waiting for the uncertain economic air surrounding the growth-austerity debate, the opaque level of bad debts, and major financial credit constraints to clear.

During the 1990s when Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke was an economics professor at Princeton studying the deflationary Japanese economy, he proposed a simple three-step solution for the notoriously hesitant Japanese ruling class: first, recognize the bad debts and fix the banks because you cannot have economic stability without financial stability; second, aim for a devalued currency through aggressive monetary reflation efforts because low bond yields do not always reflect an easy money policy; and third, experiment aggressively with new policy measures to help raise the structural growth rate because delay can be very costly. For the most part, Bernanke’s sound plan has been implemented in the US. In our opinion, this is one reason the US economy has been holding up better than its competitors.

THE SOLVENCY TRAP

Central bank balance sheets have exploded in an attempt to encourage portfolios to rebalance into riskier assets, but still investor risk appetite swings between risk-on and risk-off. Bad debts languishing on bank balance sheets create excess capacity and cut the yield (or expected rate of return) on capital investments. Reluctance to recognize bad debt is a significant force propelling this risk oscillation, which brings us to the solvency trap.

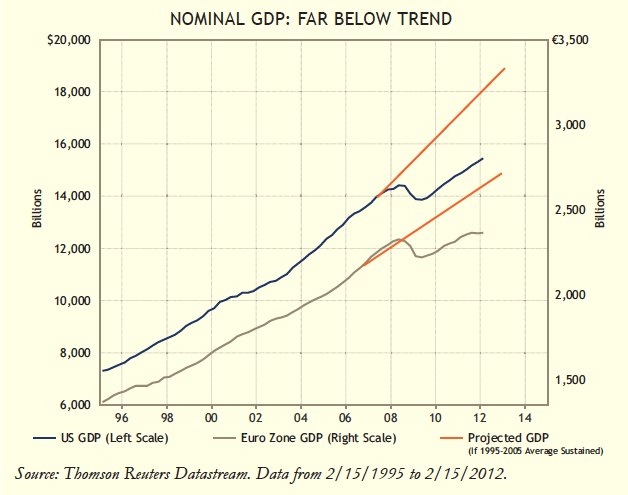

Estimating the level of bad debts is often an opaque exercise. To visualize how bad debts can pile up, consider how far below trend nominal gross domestic product (GDP) has fallen in both the US and Europe (see the chart on the next page). Nominal GDP and top-line revenue growth are highly correlated. For example, if a bank extended loans based on the strong expected trend level of nominal GDP in 2007, and those projections turned out to be bad estimates, those loans could be rotting on the bank’s books. Lenders generally prefer to extend bad loans in the hope that asset prices, profits and incomes might recover to a level that would make the loans whole. But this exercise delays cutting the rot from the system and leaves a level of excess capacity that can lower the expected rate of return on both good and bad businesses.

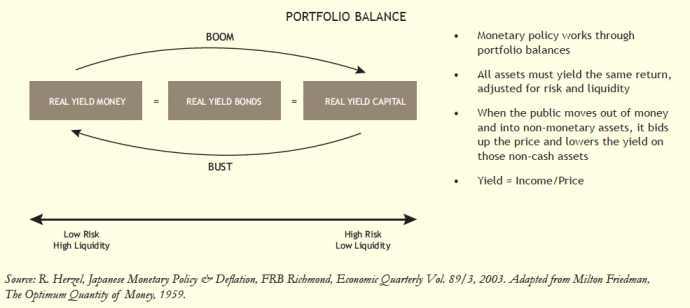

The portfolio balance diagram below highlights how the solvency trap can short circuit an economic expansion. To encourage an economic expansion, a central bank normally lowers the yield on money, which prompts investors to rebalance their portfolios into higher-yielding assets like bonds and capital investments. Portfolio rebalancing tends to drive bond and capital investment prices higher, sending risk-adjusted yields lower. As these assets appreciate in price, the wealth effect encourages greater consumption and demand. Collateral values continue to improve as prices rise, enabling more borrowing and spending. This process helps the economic cycle become more complete and self-sustaining.

Low risk appetite, excess capacity, and a high suspected number of bad debts in the system can short-circuit the portfolio rebalancing process. In this case, the risk- and liquidity-adjusted yield on risky bonds and capital investments is not sufficient to compete with the yield on money. Enter the solvency trap. Even if the yield on money is zero, the risk-adjusted expected rate of return on an investment in an insolvent country, bank, or company is less than zero because investors anticipate a capital loss, and central bank efforts to reflate the economy stall. Capital becomes trapped in money and high-quality bonds, like the scenario we see today. Writing off bad debts can help clear uncertainty, assuage risk aversion and shrink excess capacity, all of which should help raise the yield on capital investments and encourage portfolio rebalancing.

CONCLUSION

It has been five long years since the latest financial crisis began, and we are still wringing our hands wondering whether the recovery is sustainable. The low level of government and high-quality bond yields signals anemic confidence and serious deflationary threats. We believe policy makers need to be more aggressive in pumping liquidity and capital into the system. In the nearer term, the next fix from the Fed might be QE3 or an extension of Operation Twist at the end of June. Europe needs to decide which countries will remain in the euro, mutualise its debt and put real capital into the banks. The other big liquidity provider, China, can ease policy further but probably by much less than it did during 2008 because inflationary constraints are tighter today.

While money and liquidity are necessary, they are not sufficient to solve these problems. Investors are fond of saying that liquidity cannot fix a solvency problem. The real silver bullet is economic growth; it drives the profits, jobs and incomes that service debts and lessen the threat of insolvency. Currently, instability in the financial system and the opaque level of bad debts are major impediments to sustained economic growth. Policy makers, in our opinion, should listen to Bernanke and fix the banks, devalue the currency, and keep trying until they get it right.

Indexes are unmanaged and do not incur fees. It is not possible to invest directly in an index. Past market experience do not guarantee future results.

This report is provided for informational purposes only and should not be construed as investment advice. Any opinions or forecasts contained herein reflect the subjective judgments and assumptions of the authors only and do not necessarily reflect the views of Loomis, Sayles & Company, L.P., or any portfolio manager. Investment recommendations may be inconsistent with these opinions. There can be no assurance that developments will transpire as forecasted and actual results will be different. Data and analysis does not represent the actual or expected future performance of any investment product. We believe the information, including that obtained from outside sources, to be correct, but we cannot guarantee its accuracy. The information is subject to change at any time without notice.

Copyright © Loomis Sayles

MALR009270 LEGREV012513