Sustainable spending also has merit within an asset class. Consider equities; we’ll use our Fundamental Index® approach for illustrative purposes.7 The basic Research Affiliates Fundamental Index (RAFI®) strategy annually rebalances each stock back to its fundamental business scale. While the RAFI strategy uses multiple measures of a company’s economic footprint, let’s simplify by considering dividends alone. If a stock soars relative to the rest of the market, and its yield tumbles, what will a Fundamental Index strategy do? This stock will typically be trimmed, with the proceeds rebalanced into another stock with a higher yield. In so doing, the rebalancing in RAFI strategies raises our dividend yield. With each rebalance, we’re taking on Mr. Market’s most hated “projects,” the feared and loathed deep value stocks.

What if value has performed poorly? Then, value stocks will likely have become cheaper, while growth stocks will have become more richly priced. In this case, a RAFI strategy will likely rebalance out of growth and into value, more aggressively than normal. The rebalancing increases our dividend yield, as well as our sustainable spending! Will a RAFI strategy ever trade out of value and into growth? Yes, but rarely. This occurs when value has outpaced growth by a wide margin.

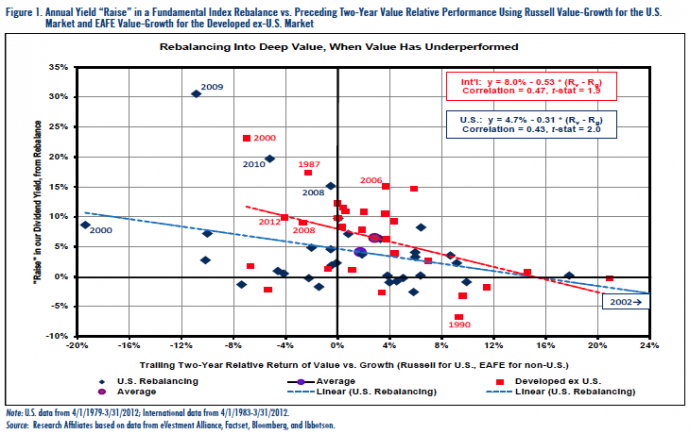

The pattern of rebalancing is confirmed in Figure 1 for U.S. and Developed non-U.S. stocks. Each dot represents a single year’s rebalance. The FTSE-RAFI® US 1000 Index rebalance at the top of the tech bubble (the left-most blue dot, labeled “2000”) illustrates a big rebalance in which the portfolio yield rose from 2.34% to 2.53%, for an 8% jump in the portfolio income. The size of the rebalance was triggered by a 24-month period in which Russell Value lagged Russell Growth by a staggering 19% per year. Mr. Market just gave us an 8% raise, in real income, for allowing him to trim his most feared deep value names, even as we gave him more of his favorite high-fliers. Mr. Market was even more generous with the FTSE RAFI Developed ex US Index rebalance in that same year (the top red dot, labeled “2000”). In this case, EAFE Value had underperformed EAFE Growth by 7% per year in the prior 24 months. Because value had become so cheap—was so loathed by Mr. Market—our Fundamental Index portfolio moved from a dividend yield of 2.5% to 3.1%. In this case, Mr. Market gave us a 24% raise in real income.

Of course, 2000 was an exceptional year, the peak of the largest market bubble in history.8 In more normal times, this type of rebalancing provides about a 4% extra raise—beyond what Mr. Market offered to his “passive” employees—in the United States and about a 6.5% extra raise in the Developed ex U.S. markets. Our willingness to take Mr. Market’s most loathed holdings leads to a boost in our income about three-fourths of the time: 24 out of 33 years in the United States and 22 out of 28 years in the international markets. These “raises” are over and above whatever increase Mr. Market is offering as a “company-wide” average.

Mr. Market has another peculiarity that bears mentioning. The worse value has performed—and the worse we’ve performed as a consequence of our previous willingness to embrace value—the bigger the raise that Mr. Market will give us for taking a still larger slice of his most loathed holdings. Obviously, it requires tremendous courage to rebalance into the same deep value names that just hurt us. But Mr. Market is a thoughtful boss: If we took on a project that he hated, and we got burned last year by doing so, he wants to make it up to us with an even larger raise to ease our pain… as long as we’re willing to do it again! We can see this in the larger “raise” in our dividend yield around inflection points, which includes 2000, 2008, and 2009, as well as 2012 for our non-U.S. holdings.

In the case of developed equities outside the United States, the recent crises deliver far more yield—if we’re willing to rebalance into the recently savaged deep value stocks in Europe and the emerging markets. Uncomfortable? You bet. Assured of success? Of course not. But, we did get a 10% “raise” in the March 2012 rebalance, from a 3.8% yield to a 4.2% yield, as recompense for stepping “once more into the breach.”9 A 4.2% yield is a very nice start toward a goal of earning solid real returns.

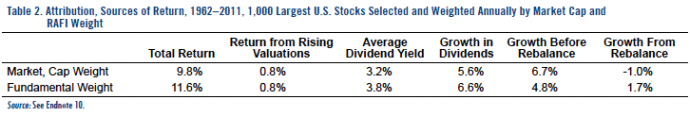

A skeptic might suggest that we shouldn’t get to keep the extra yield, if the market is properly discounting future dividend cuts among the recent price laggards. History suggests otherwise. Table 2 compares the total return for a U.S. capitalizationweighted large company portfolio and a RAFI portfolio from 1964–2009 (we revert back to a U.S. series to give us the longest track record).10 As the data show, the RAFI methodology earned an average dividend yield of 3.83% since 1964, nearly 70 basis points per annum better than cap weighting. And, there’s a bonus—the Fundamental Index approach gives us an annualized dividend growth rate of 6.6% per annum, a full percentage point per annum above the cap-weighted market.

How can we be garnering faster dividend growth, especially in light of our tendency to shun the most beloved growth stocks? Again, it’s our rebalancing, as we can see when we segregate the growth in our existing holdings’ dividends from the “raise” we derive from rebalancing. The value tilt of the Fundamental Index approach garners 1.9% slower growth in buy-and-hold dividends, before the rebalance, relative to the more growth-oriented holdings of a cap-weighted portfolio. This then offsets the yield difference. But the annual rebalance ratchets that yield up by 1.7% on average, while cap weight drops its losers and chases its winners, costing it 1% per year on its own rebalance. We garner an average “raise” of 2.7%, with each rebalance, as recompense for tolerating discomfort, instead of chasing the latest high-fliers; for international stocks we garner twice as much of a “raise” as this… more than 6% each year. Add it up and we get near 2% more return than cap weight per year (for nearly a half-century!), and considerably more outside the United States. All for taking on Mr. Market’s most hated “projects” year after year.

Conclusion

Rebalancing into the most feared and loathed stocks, and out of the most beloved high-fliers, requires courage—even if we get a “raise” almost every time we do it! Andrew Ang of Columbia labels this “countercyclical investing.” He calls on long-term investors to institutionalize this kind of contrarian behavior.11 If we have the courage to do this, even though it creates discomfort and goes against human nature, it far better aligns our investments with the long-term obligations that they are intended to serve.

Over the long term, we get better total returns by investing for a steady increase in sustainable spending, while letting others invest for comfort. Fortunately, Mr. Market is a kindly boss, rewarding us handsomely for our courage in taking on his most hated holdings. The willingness to apply courage, in a disciplined and contrarian fashion, leads to better long-term results.

Institutionalizing a focus on sustainable spending, as a basis for gauging our investments over time, can help give us the courage to stay the course in adversity and even to take on more discomfort when it is most profitable—and most frightening—to do so.

Endnotes

1. Ben Graham was perhaps the first to personalize the market, by calling it “Mr. Market.”

2. See Arnott, Robert D., 2004, “Sustainable Spending in a Lower-Return World,” Financial Analysts Journal, vol. 60, no. 5 (September/October):6–9.

3. See Garland, James P., 2004, “The Fecundity of Endowments and Long-Duration Trusts,” Economics and Portfolio Strategy, September 15.

4. See Arnott, Robert D., and Peter L. Bernstein, 1997, “Bull Market? Bear Market? Should You Really Care?” Journal of Portfolio Management, vol. 24, no. 1 (Fall):26–29.

5. I prefer to use the cost of an inflation-indexed annuity to define sustainable spending. Dividends are a perfectly good proxy because dividends generally rise with inflation, plus delivering Mr. Market’s

average 1–2% real raise.

6. The phrase “No Guts, No Glory” was popularized by Captain Frederick “Boots” Blesse, an ace jet pilot from the Korean War. Upon returning home, Blesse used his experience to publish a manual on

fighter tactics, “No Guts, No Glory,” which was used in training by the United States and other air forces. In the preface, Blesse stated that “…the goal which we seek, or should be seeking, in the

training of any pilot, is to produce a pilot who is aggressive and well-trained.”

7. The same lo gic applies to any method that doesn ’t invest proportionately to shar e price, as cap w eighting does.

8. With apologies to the EMH academics who still think that Pets.com was fairly priced in early 2000!

9. Shakespeare, Henry V, during the famous battle at Agincourt.

10. This table is drawn from Robert D. Arnott and Denis Chaves, “Rebalancing and the Value Effect,” forthcoming in the Journal of Portfolio Management, Summer 2012.

11. See Ang, Andrew, and Knut N. Kjaer, 2011, “Investing for the Long Run,” November 11. http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1958258.

Copyright © Research Affiliates (RAFI)