- In assessing the possibility, duration and impact of systemic risk factors, we need to analyze the interaction of expectations with market (endogenous) and policy (exogenous) circuit breakers.

- In the current environment, the prevalence of some subjective bimodal expectation distributions (e.g. Europe related) speaks to the multiple equilibrium features of sovereign debt markets.

- Multiple equilibria give rise to a range of scenarios, each quite different and each with its own distribution of returns, risks, correlations, and market functioning.

- In today's global context, investors (as well as policy makers, researchers and opinion leaders) need to supplement their analyses of fundamentals, historic risk premia, correlations and relative value with a clearer delineation of the expectation formation process itself.

Introduction

Financial markets are subject to periodic bouts of systemic risk that affect their functioning and stability, as well as investment returns and volatility. Several elements of investment strategy – including asset allocation, liquidity management, risk mitigation and, in certain cases, even the design of benchmarks and guidelines – can be affected by this reality. Accordingly, and particularly given the ongoing re-alignment of the global economy and markets, it is important to have a handle on the underlying dynamics. To this end, in this paper we analyze those associated with sudden shifts in expectations. It explains how they can morph into particularly disruptive multiple equilibria dynamics, and it points to possible implications for market outcomes, market equilibria and policy responses.

The Context

Earlier work in economics on signaling and screening, including by one of the authors of this article (Mike Spence), sheds important light on issues that are of current interest to markets and investors. Specifically, a significant subset of multiple equilibrium market structures – the ones that are most relevant to financial markets and to their interactions with the real economy – are those in which expectations have two characteristics: First, the expectations are endogenous – i.e., they are determined as part of the process of reaching equilibrium outcomes in the market. Second, they exert a substantial influence on behavior and hence on the market outcomes that are inherently linked with the expectations themselves.

The interactions of these two factors are critical. Indeed, if they are misunderstood, they can easily result in inappropriate analyses, investment decisions and risk management. They also can lead to misguided policy reactions.

If just the first characteristic is present, markets are in equilibrium when expectations are accurate. However, if both are present, then expectations aren’t best described as accurate but rather self-confirming in a serial manner; and the sequence of local equilibria need not lead to a global equilibrium. Consequently, it is this kind of structure that has multiple equilibria and hence the potential sudden shifts in both expectations and equilibrium market outcomes.

For financial markets, balance sheets and the real economy, the endogeneity of expectations is always part of the structure. But shifts in expectations and asset values need not always cause powerful feedback effects on investor behavior and/or the real economy. They do when a slight initial perturbation in expectations is amplified into a rapid, non-mean-reverting shift to a very different set of outcomes.

In assessing systemic risk, we therefore need to look for the conditions where there are substantial feedback effects and where market or policy circuit breakers are either missing, incomplete or uncertain.

Signaling as an Example of a Multiple Equilibrium Structure

Signaling occurs in market environments in which there are both informational gaps and informational asymmetries between the buyers and sellers. That is, there is some attribute of the product or service about which one side knows more than the other.

Asymmetrical information conditions are quite common. They occur in labor, financial and insurance markets, and in many more places. As an example, in insurance markets, the observability gap is variation in risk across the entities seeking to buy insurance. This phenomenon is called adverse selection. It leads to sub-optimal outcomes and market failures.

Incomplete information and the inability to distinguish cause a loss of product differentiation. Sellers try to recover the differentiation through signaling. For buyers, signals are visible attributes that sellers can acquire at a cost that, in turn, transmits information to buyers. Signals that survive and contain information in equilibrium have the property that their costs are negatively correlated with the invisible, valued attribute. If that condition is absent, the hypothetical signaling behavior of sellers will not be correlated with the underlying attribute. Subsequent market outcomes will reflect that, and the signal then loses its informational content and falls into disuse and out of the market equilibrium determination mechanisms.

Signaling has the two properties described above: Expectations are endogenous; and they exert a powerful influence on both incentives and choices made by sellers. Signaling models have multiple equilibria, in each of which the expectations are self-fulfilling.

In the current environment of large correlated global macro risks, we naturally tend to think mainly of dangerous equilibrium shifts – away from good ones and toward unfavorable bad ones that are also potentially unstable in that one bad equilibrium gives way to even worse ones in a serial fashion. But, importantly, it can go the other way too.

Yes, you can get stuck in a “bad” equilibrium. For example, in the developing country context in the early stages of development, there is an equilibrium in which there is relatively little growth and suboptimal investment – a bad equilibrium if you like. Any shock, endogenous or exogenous, carries a high risk of tipping the country into an even worse equilibrium. In such circumstances, the leadership and reform challenge is to shift the expectations and hence the underlying investment dynamics to a different and much more positive equilibrium. And it is here that a series of positive equilibriums can impose themselves, with significant implications for investment returns.

Ordinary Market Dynamics: Momentum and Value Investing

Financial markets have endogenous expectations. Investors know that expectations and prices can drift away from fundamentals, with a dynamic driven largely by the self-referential nature of the expectations. But there are limits.

In “normal” conditions, the feedback effects of asset price movements on the balance sheets of financial and other institutions (and of households) are not that large; and the wealth effect on activities in the real economy is small as a result. Moreover, arbitrage flows are subject to relatively low liquidity and risk premia.

So while a set of investors may base their choices on momentum and charts, others counter by basing their decisions more on deviations of market prices from some assessment of fundamental values, either short- or long-term. Trading frequency varies, as does the degree of dynamic portfolio reallocations and the premium that can be collected for selling volatility in different market segments.

Generally investors know that at least short term returns are determined in part by other investors’ expectations, but longer-term valuations will revert to levels warranted by the underlying fundamentals. As certain traders cause markets to move away from fundamental values (a mini bubble), the deviations become larger relative to the distribution of underlying value estimates. This entices value investors to move against the trends, thus causing a shift in the market dynamics back toward the central part of the fundamental value distribution.

Depending on the size and responsiveness of assets managed by each class of investor, the deviation from fundamental values can persist for awhile, but it gets pulled back. This can be thought of as a relatively harmless form of fluctuating multiple equilibrium. And it tends to give rise to attractive premiums that investors can capture by selling volatility, either directly in a range of markets (e.g., interest rates, credit, equities, commodities and foreign exchange) or indirectly and less comprehensively through certain asset classes (e.g., mortgages, corporate bonds, and emerging markets’ local rates, credit and equities).

In this rather common dynamic, the deviations are generally mean reverting as expectations shifts do not substantially affect fundamental values. This is not the case when, critically, feedback effects are large and the valuation anchor morphs into a moving target.

For example, in the aftermath of the 2008 crisis, the real economy headed down a highly correlated downward spiral along with the financial markets. Leverage caused a substantial part of the problem, as did pro-cyclical behavior on the part of markets and investors. The result was a significant, across the board repricing of markets, along with “atypical” developments in market correlations and the range of risk premia (including the liquidity premium). As a result, initial changes in asset values that in an unleveraged world would not have produced large real economy effects caused substantial balance sheet damage in the highly levered financial and household sectors. This led to large negative real-economy feedback effects and declining fundamental values. It wasn’t clear what the anchor was, or if there was one. That kind of structure can implode; and it would have were it not for dramatic and unprecedented intervention on the part of policy makers who aggressively substituted public balance sheets for rapidly imploding private ones.

The small feedback condition that we associate with normal stable market conditions was arguably also not what we saw last year in the European sovereign debt markets. Then, a yield run up in Italy or Spain threatened to shift the trio of market, political and policy incentives in such a way that it would have a major effect on credit quality. This had occurred already in Greece. More on this later.

Bank Runs

Multiple equilibrium structures are not new. History is full of examples where, absent effective policy circuit breakers, market realities deviated considerably from fundamentals, and did so in a sequential and increasingly disorderly fashion.

Consider the case of the banking sector. The normal levered configuration of banks (in a narrow sense, these are associated primarily with their maturity transformation as short term liquid liabilities fund longer-term and less liquid assets) is key to their role in funding productive investments in an economy. But it also makes them vulnerable to losses of confidence – a situation that was massively accentuated in the run up to the global financial crisis by prop activities and off balance sheet structured investment vehicles (SIVs) and other shadow banking activities.

Sometimes the change in operating paradigm is real, in the sense that the assets suffer some kind of permanent impairment resulting in negative equity. At some point depositors and creditors notice and a race for the exit starts. But as often observed, you do not need such a solvency shock to start a bank run. Just the perception of such a risk will do. Why? Because it is self-fulfilling absent government and central bank intervention. In such situations, solvency itself becomes endogenous.

Extreme bank runs are uncommon these days because governments guarantee deposits and central banks can and do move quickly to monetize the asset side of a solvent bank fast enough to keep it in business, even if the deposit run continues for some time, or if short term private financing in the market is cut off. Eventually the deposit run reverses, borrowing capacity returns, and the original equilibrium is restored.

The Internet Bubble of 2000-2001

The internet bubble of some 10 years ago is an interesting and slightly different case. Valuations of informational technology assets (publicly traded and not) got disconnected from reality, and had some of the characteristics of mini-bubbles described above. But the deviations from fundamental value were quite extreme.

The value investor market correction was delayed by the newness of the technologies and the temporary absence of relevant data to constrain the expectations. In this data-free environment, narratives, unconstrained by relevant experience (there wasn’t any), dominated, usually with a revolutionary, disruptive technology flavor. However, the data-free condition was not permanent. Eventually it became clear that, at least in the short term, forecasts of growth, relevance, revenues and earnings were way too optimistic. The markets experienced a major downward reset, with real economy effects that were large enough to cause a recession.

With hindsight, it seems fairly clear that the market distortions were not caused by an inaccurate specification of the ultimate impact of the technology. Instead, it was the substantial overestimate of the speed with which these new technologies would affect productivity, society and the global economy.

There are a variety of ways to describe this. Essentially, the value-investing anchor was present but much delayed. There were value and activist investors who were skeptics but, in the early stages, either they were less numerous in terms of control over assets or less certain of their views – hence the delay in responding.

The internet bubble was sufficiently large that it did, via the wealth effect, produce a shift in the trajectory of the real economy. For a while this effect was positive and reinforcing. But when expectations shifted and valuations reset, the reverse occurred and the real economy dipped to the point that the central bank opted for low interest rates to cushion the recessionary effect.

Standing back from these specific two cases for a moment, something is clear. In both, there were multiple equilibria affecting market activity, policy anchors and circuit breakers; and they ended up operating with varying speed and certitude.

Sovereign Debt and the Eurozone

Olivier Blanchard, the chief economist at the IMF, observed in his 2011 end-of-year remarks: “… post the 2008-09 crisis, the world economy is pregnant with multiple equilibria – self-fulfilling outcomes of pessimism or optimism, with major macroeconomic implications.”

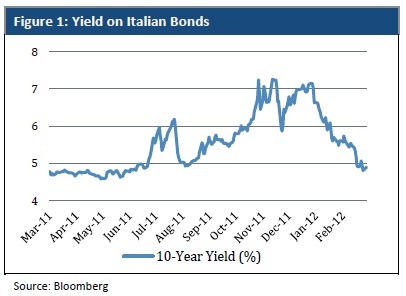

Consider the case of Italy last year. In May, Italian bond yields were relatively stable and well behaved. By August and again in November onward, unprecedented volatility drove them to dangerously high levels – enough to raise legitimate concern about the risk of a debt insolvency sequence.

With yields in the 6% to 7% range and the prospect that they might remain high as maturing low cost debt was increasingly refinanced via high cost debt, there was a material risk of a shift in expectations – not just on the market side, but also on policy incentives. The interactions of these expectations, including through feedback mechanisms, translated into mounting pressures on credit quality, yields, growth and policies. They also had social and political effects. And as the Italian stock market lost a third of its value, the wealth effect kicked in, helping to push Italy’s economy toward negative growth and debt deflation.

Sovereign debt in this context assumes the structural characteristics of multiple equilibria. The “credit risk” is endogenous. Perceived risk affects investor behavior, market prices, the incentives of governments and hence credit risk.

What are the circuit breakers or anchors in a situation like this? One parameter is the level of sovereign debt. Italy’s public debt-to-GDP is second only to Japan among the G-7 economies. That makes the cost of a rise in yields considerable.

In the low leverage case, you could argue that the anchor is the relatively low cost to the public finances of a rise in yields, breaking the feedback effect on credit risk. In that case, value investors respond to yield increases by increasing exposures and bringing the yields back down. Higher debt flows do the opposite: They change the incentive structure and amplify the feedback effect.

Second, with respect to a sudden shift in equilibrium, anticipated policy responses matter. In the Italian case, an aggressive assault on tax evasion, measures to liberalize labor markets and lift growth, and to dial back the parameters that determine non-debt public liabilities like pensions, with enough leadership to overcome the burden-sharing inertial forces that are present in any political system, would clearly reduce (though not eliminate) the risk. By contrast, prior to the arrival of the technocratic government under the leadership of Prime Minister Mario Monti, Italy had a government that was distracted, perhaps not fully aware of the risks, and losing popular support (as well as that of European partners). Even if it had attempted the kind of reform program that would have made a difference, there was heightened risk that probably tipped the markets toward the new equilibrium.

With a change in government and in policy approach, including meaningful support from the ECB via the long-term refinancing operations (LTROs), Italy had the ability to interrupt the negative multiple equilibrium dynamics at the end of 2011/beginning of 2012, thus lowering its borrowing costs. That was not the case for Greece, where the initial economic and financial conditions were considerably worse, there are legitimate questions about the political will to implement and sustain the reform process, and European partners and the IMF appear much more skeptical and hesitant.

The general awareness of the seriousness of the problem has risen substantially, but the issue of who across various parts of the economy and externally should bear the real costs of restoring fiscal balance and growth momentum remains. Even with the recent debt restructuring operations, or PSI (for private sector involvement), markets are pricing remaining unallocated capital losses that act as an impediment to solvency, growth and employment. As a result, fresh capital is largely refusing to engage notwithstanding yields that remain high.

It is important to stress the complementary potential circuit breakers formed by the external policy response – namely, the scale and scope of intervention from the ECB, EU and IMF (the “troika”) in the sovereign debt markets experiencing rising yields that threaten the effectiveness of and commitment to reform measures.

These entities’ interventions can and in some cases have succeeded to stabilize yields, buying time for the reform process to work. This is the case for the powerful LTROs.

By providing “unlimited liquidity” to banks on truly exceptional terms (1%, three-year maturities, and relaxed collateral requirements), the ECB has been instrumental in easing forced de-leveraging, minimizing the risk of disorderly deposit outflows, and preventing highly disruptive bank runs and payments problems. Some of that intervention also spilled over to sovereign debt markets.

But thus far, the ECB and the eurozone core have been unwilling to make unconditional commitments to intervene directly in the sovereign debt markets of Italy and Spain to stabilize yields. This reluctance is understandable and is probably due to concern about what might be called political or policy moral hazard: The concern is that such a commitment, while reducing the likelihood of the unattractive equilibrium, other things equal, might also reduce the incentive for reform by politicians and citizens. Since such reform is acknowledged to be essential to restoring stability in the eurozone, depending on which effect is larger, the intervention could be self-defeating.

Many knowledgeable observers believe that the intention in the eurozone core is to intervene, provided the reform process is serious and making headway, but not to announce this intention in order to mitigate the moral hazard problem. The problem then becomes the balance between proactive and reactive measures, as well as the ability to crowd in the private sector.

A similar kind of political moral hazard may have motivated German Chancellor Angela Merkel’s decision to insist on a parallel process of fiscal reform, in spite of the fact that such a process burdens a political construct that is already challenged by the process of restoring order in the periphery. The theory being that, in the sequential version, if and when things are stabilized, the incentive to do the institutional reform declines among politicians and electorates. It is a complex situation.

The USA and Japan

If this analysis is correct, then as the U.S. runs up its sovereign debt over time, there will be a gradual increase in the risk of a sudden shift in sentiment/expectations. Down the road, this could lead to an increase in yields and hence reduce fiscal space and policy flexibility. Political gridlock adds to this risk by lowering the perceived capacity to engage in corrective medium-term action on a timely basis, or to credibly commit to a multi-year term plan for fiscal stabilization and growth.

If expectations start to deteriorate on U.S. sovereign debt, there is no plausible external circuit breaker. It has to come from within the country. And the only plausible anchor to pull it back would be strong, disciplined, multi-year policy response that targets, importantly, both lower debt and higher growth. The longer it is delayed, the more expensive and riskier it becomes. While the leverage is probably not yet high enough to make the current equilibrium unstable, the return of the threat of a technical default in late 2012 or early 2013 could move the risks forward in time.

The U.S. Economy in the Decade Prior to the Crisis of 2008

The U.S. economy prior to the crisis was running with excess consumption, deficient public sector investment, government dis-saving, and a current account deficit reflecting a shortfall of saving relative to gross investment. In short, the economy was investing too little to sustain growth and saving even less.

Unlike other major developed economies, the U.S. ran a bilateral current account deficit with respect to almost every major country. Income and wealth distribution continued to deteriorate, and net employment creation in the tradable side was negative with especially large declines for the middle-income groups. The non-tradable side of the economy absorbed the incremental labor force with big increases in government and health care and a boost from excess consumption, especially in the labor intensive sectors, retailing, hospitality and construction.

Both the structural imbalances and the accumulation of public and private debt should have raised questions among policy makers and investors about the sustainability of the growth pattern over the medium-term, especially in the non-tradable sector, as well as about the political economy and distributional effects. But all of this is with the benefit of hindsight. Too many were insufficiently attentive to the powerful secular technological and global economic forces operating on the economy, overly sanguine about the sustainability of the growth pattern, and unable to accurately assess the rising systemic risks. As a result, on a rather large scale, the market and policy circuit breakers failed to operate, and eventually the equilibrium shifted suddenly and violently.

The crisis of 2008 wasn’t so much a 100 year storm but rather an accident waiting to happen. It is true that failures of regulation and risk assessment played important enabling roles. But the underlying problem was in large part a systematic pattern of unsustainable intertemporal choices, reflected in leverage, debt and a sense of unlimited credit entitlement. This led to a dynamic in both the real economy and the markets that constituted an increasingly unstable equilibrium. It broke in 2008, and we are in the somewhat lengthy process of shifting to a different equilibrium, what PIMCO labeled back in May 2009 the bumpy journey to a new destination (or a “new normal”).

Assessing non-cyclical macro systemic risk is complex: Accurately gauging the likelihood of an equilibrium shift is hard, and as a result, the anchors that prevent major deviations from realistic sustainable long run value creation are not necessarily present. But one lesson for policy makers and investors seems clear: It is unwise to assume stability and sustainability when underlying fundamentals are weakening.

Tipping Points

It is not enough for investors and policymakers to recognize the fuel for multiple equilibria dynamics. There is also the question of the spark, or what is known as tipping points.

Tipping points are shifts in the equilibrium when either fundamentals or expectations change course and then are legitimized by subsequent developments. Often they occur quite suddenly, with accelerations coming from technical factors. The exact timing is notoriously difficult to predict, raising the challenges for how markets, investors and policies should react and internalize/price this non-linearity.

From recent experience, question marks or changing views about policy responses increase the likelihood of an equilibrium shift by operating directly on the expectations. New data can have the same effect. Also, observation of market dynamics suggest that there are narratives and stories that affect investor behavior, and that when these narratives change, expectations and pricing dynamics can shift too.

But even for contrarians who detect the structural conditions early, predicting the timing has proved elusive, and the duration of the contrarian bet can be uncomfortably long. Generally, most scholars and analysts have concluded that it is impossible to predict the timing of an equilibrium shift even when the ingredients that create the rising potential instability and the possibility of multiple equilibria are present. The analogue in the sciences are systems that are called “critical states” whose movements behave according to fat-tailed power law distributions.

Bimodal Distributions, Multiple Equilibria and Investment Strategy

In the current environment, the prevalence of some subjective bimodal distributions on the part of investors can be viewed as a reflection of the multiple equilibrium features of a number of sovereign debt markets. This is especially the case in Europe where investors are torn between the prospects for fragmentation (reflecting both default and exit risks associated with the weakest eurozone peripherals) and recovery (driven by the core’s commitment to “refounding” the eurozone and the periphery’s adjustment efforts). Here the ramifications of a sudden equilibrium shift, good or bad, go well beyond the sovereign debt markets themselves, radiating out to the entire global economy.

Multiple equilibria give rise to two or more scenarios, each quite different and each with its own distribution of outcomes, correlations, market functioning and returns. Investors – and especially long-term investors in both financial and physical assets – are faced with the need to assess the relative likelihood of the scenarios, and then take a weighted average of usually two rather more normal looking distributions to end up with the bi-modal one. Whether it is in fact bimodal or not depends on the weights. Extreme optimism or pessimism will eliminate the bimodal feature.

This suggests that the tipping point can be crossed when the relative weight given to the non-status quo scenario starts to rise for a subset of investors. There is some emerging evidence that the short-term correlations, across and within asset classes, start to rise before a possible equilibrium shift. But that does not imply that the shift will occur. And when the correlations rise, the cost of the tail risk hedges also tends to rise.

Boldly betting on one or the other of the scenarios – i.e., either an extreme risk-off or risk-on posture – requires a very high level of conviction and foundation in an inherently “unusually uncertain” context. Similarly, positioning for the average of the two modes means that investors end up in the muddled middle – a “carry-laden” portfolio positioning that pays off only if the unsustainable is sustained.

A better approach revolves around the early detection of the structural bases for multiple equilibria accompanied by relative low cost tail-risk hedges. Absent that, for many investors, sitting on the sidelines and accepting low cash returns (and, in today’s policy-induced financial repression environment, negative real rates) until the bimodal features are resolved is understandable. How to do that used to be via a basket of “risk-free” assets; but with sovereign debt risk in the major economies on the rise, the menu of “risk-free” assets is being reduced, and yields on what remains have converged to very low nominal levels.

Conclusions

With too many advanced economies confronting the twin dilemma of too much debt and too little growth, and with systemically important emerging countries navigating the tricky middle-income developmental transition, today’s global economy poses unusual challenges for traditional concepts of asset allocation and risk management. It is also slowly influencing the way that certain investors are thinking about correlations, volatility, guidelines and benchmarks.

These changes can be particularly pronounced in situations where markets transition from a mean-reverting paradigm to one of multiple equilibria and path dependency. This is the world in which expectations can and do play a major role in economic and market outcomes.

On the negative side, the global economy saw this dramatically back in 2008-09, and Europe has been experiencing it more recently. Moreover, it featured in many of the historic bubbles and bank runs that are still the subject of analysis and fascination. On the positive end, it has characterized the beneficial breakout phase in several emerging economies. We also saw it in the reactions of markets to circuit breakers imposed by decisive policy actions on the part of several countries in 2009.

In such cases, successful investors (as well as policy makers, researchers and opinion leaders) have to extend well beyond their understanding of fundamentals, historic risk premia, correlations and relative value. They have no alternative but to also try to understand the expectation formation process itself, including agent signaling and feedback loops incorporating economic outcomes and incentive structures. Without such understanding, it becomes even harder to continuously succeed in meeting objectives – especially in a world that will continue to de-lever and where policy makers are still in full experimentation mode.

Both theory and the experience of the last few years suggest that investors must also enhance their analysis of policy makers’ reaction function. Indeed, this is an important input into assessments of correlations, volatility, returns and risk.

For policy, this points to a need for a better design and use of ex ante and ex post circuit breakers. The former prevent the evolution of structures that amplify the feedback loops. The latter are designed to break the serial contamination of expectations, the real economy and market linkages, thereby interrupting the often disruptive dynamic that leads to a sequence of bad equilibria.

A "risk free" asset refers to an asset which in theory has a certain future return. U.S. Treasuries are typically perceived to be the "risk free" asset because they are backed by the U.S. government. All investments contain risk and may lose value.

Investing in the bond market is subject to certain risks including market, interest-rate, issuer, credit, and inflation risk. Equities may decline in value due to both real and perceived general market, economic, and industry conditions. Investing in foreign denominated and/or domiciled securities may involve heightened risk due to currency fluctuations, and economic and political risks, which may be enhanced in emerging markets. Sovereign securities are generally backed by the issuing government, obligations of U.S. Government agencies and authorities are supported by varying degrees but are generally not backed by the full faith of the U.S. Government; portfolios that invest in such securities are not guaranteed and will fluctuate in value. Mortgage and asset-backed securities may be sensitive to changes in interest rates, subject to early repayment risk, and while generally supported by a government, government-agency or private guarantor there is no assurance that the guarantor will meet its obligations. Tail risk hedging may involve entering into financial derivatives that are expected to increase in value during the occurrence of tail events. Investing in a tail event instrument could lose all or a portion of its value even in a period of severe market stress. A tail event is unpredictable; therefore, investments in instruments tied to the occurrence of a tail event are speculative. Derivatives may involve certain costs and risks such as liquidity, interest rate, market, credit, management and the risk that a position could not be closed when most advantageous. Investing in derivatives could lose more than the amount invested.

This material contains the opinions of the author but not necessarily those of PIMCO and such opinions are subject to change without notice. This material is distributed for informational purposes only and should not be considered as investment advice or a recommendation of any particular security, strategy or investment product. Information contained herein has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, but not guaranteed. No part of this material may be reproduced in any form, or referred to in any other publication, without express written permission. ©2012, PIMCO.