When speaking to investors I have found that a majority still believe the Spanish banking industry to be relatively well capitalised and able to withstand the current crisis. In my opinion this view fails to acknowledge the substantial number of local banks and savings banks which are up to their eye balls in toxic property assets.

A word on Italy

In this horror story of policy mistakes, Italy probably deserves a mention too5. Italy is one of the most indebted countries in the eurozone, so on that account it is at a disadvantage to Spain; however, several factors work in its favour. The private sector savings rate has been high for many years and most Italian sovereign debt is actually owned by the private sector in Italy. It is highly unusual for a country to default when foreign ownership of its debt is only marginal. The main risk as far as Italy is concerned is that spreads continue to widen in which case Italy would be pushed into a situation not too dissimilar to that of Portugal. We note that the spread between German and Italian government bonds has indeed widened recently and now stands at a 10-year high. I suggest you read this link for a well balanced analysis of Italy’s predicament.

Contagion risk is in CDSs

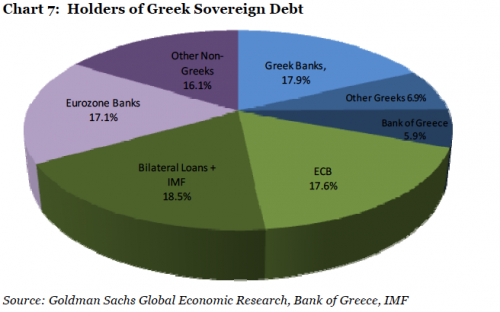

Besides the obvious contagion risk there are many other reasons why the authorities are keen to avoid a Greek default. The one most frequently mentioned is the fact that it could take down several European banks. The truth is it could, but probably not in the way you envisage. European banks are long about 17% of the €340 billion of total Greek sovereign debt outstanding (see chart 7). A 65% haircut would result in losses of €37-38 billion - not enough to create anything remotely looking like systemic risk.

No, the main risk lies somewhere else – in the CDS market. Total net risk to a Greek default is ‘only’ about $5 billion, but that number masks a much greater risk to those individual banks which have sold CDSs and which would therefore be on the wrong side of the trade, should Greece default. Total gross exposure to a Greek default is about $79 billion and, according to a recent article in the Financial Times, there may be at least one bank which stands to lose as much as $25 billion should Greece default (see here). And the problem doesn’t stop there. The very existence of the CDS market could come under threat if one of the major issuers cannot honour its obligations. They will do everything in their power for that not to happen.

Now, this is where the story gets interesting. The International Swaps and Derivatives Association (ISDA) is mandated with determining whether a default is legally a default or not. ISDA has established a number of so-called Determinations Committees (one for each geographical region) empowered to determine each and every case. I looked up on the internet who actually sits on the European committee. Surprise, surprise. Ten of the fifteen members are large international banks who also happen to be the most active issuers of CDSs (see the list here). Isn’t that a classic case of the fox watching over the chickens? If you stand to lose $25 billion, are you going to vote in favour of declaring it a legal default? There are obviously guidelines they have to follow, but...

Many other questions

There are many other questions which remain unresolved and which add to the ambiguity of the whole situation. An integral part of the Greek disaster recovery plan is to sell Greek assets on a grand scale. I just ask myself: With the ultimate outcome likely to result in a default, and with a possible exit from the euro to follow, isn’t it probable that Greece will ultimately devalue whatever currency they introduce? Who will be buying Greek assets in the face of a 20-40% devaluation?