by Robert Arnott, Research Affiliates

Stocks ought to produce higher returns than bonds in order for the capital markets to “work.” Otherwise, stockholders would not be paid for the additional risk they take for being lower down the capital structure. It comes as no surprise, therefore, that stockholders have enjoyed outsized returns for their efforts for most—but not all—long time periods.

Ibbotson Associates, whose annual data compendium1 covers U.S. stocks and U.S. bonds since January 1926, shows the S&P 500 Index compounding through December 2010 at an annual rate of 9.9% vs. 5.5% for long-term government bonds, an excess return of 4.4%. This return compounds exponentially with time. A $1,000 U.S. stock investment in 1926 would have ballooned to $3 million by December 2010 vs. $92,000 for an investment in long-term bonds, a 32-fold difference.

Emboldened by the 1980s and 1990s (when stocks compounded at 17.6% and 18.2% per annum, respectively), “Stocks for the Long Run” became the mantra for long-term investing, as well as a best-selling book. This view is now embedded into the psyche of an entire generation of professional and casual investors who ignore the fact that much of those outsized returns were a consequence of soaring valuation multiples and tumbling yields. In this issue we examine historical U.S. equity performance from a larger perspective and find that today’s overwhelming equity bias is built on a shaky foundation, reliant on a short and unrepresentative time period.

Let’s Talk Really Long-Term

For those willing to do the homework, longer-term stock and bond data exist for the United States. But that picture isn’t quite as rosy as from 1926–2010; therefore, it doesn’t receive as much attention from Wall Street optimists. From 1802–2010, U.S. stocks generated a 7.9% annual return vs. 5.1% for long-term government bonds.2 Our realized excess return was cut to 2.8%—a one-third reduction—by adding 125 years of capital markets history!

Of course, many observers will declare 19th century data irrelevant. A lot has changed! The survival of the United States was in doubt during the early part of the century (War of 1812) and during the debilitating Civil War of the 1860s. The United States was an “emerging market”! The economy was notably short on global trade and long subsistence agriculture. Furthermore, there were three major wars and four depressions—two were deeper than the Great Depression—between 1800 and 1870, a span when data on market returns were notably thin.

By the following century, the United States and its equity markets enjoyed good fortune. It was not invaded and occupied by a foreign power. It did not suffer a government overthrow… just ask Russian investors their return on capital after the Bolshevik Revolution! As Ben Graham might caution, beware the difference between the loss on capital (a drop in price, from which we can recover) and a loss of capital (100% loss, from which we cannot). Russia’s stock market wasn’t alone in the 20th century as three additional top 15 markets in 1900—Egypt, Argentina, and China—suffered a 100% loss of capital while Germany (twice) and Japan (once) came very close.3

Whether we use 200+ years or 80+ years, how many people are pursuing an investment program of that duration? No one, of course. Even “perpetual” institutions such as university endowments aren’t exempt. As the late economic historian Peter Bernstein commented, “…this kind of long run will exceed the life expectancies of most people mature enough to be invited to join such boards of trustees.”4 Relevant horizons for all “long term” investment programs are significantly shorter—10 years or 20 years, maybe 30.

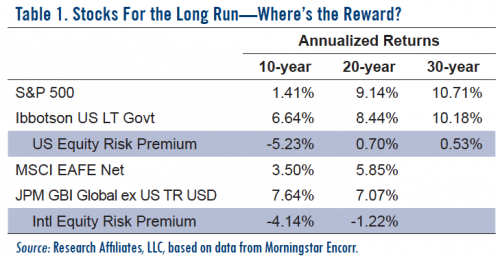

Shouldn’t a span of one, two, or three decades be sufficient for investors to be rewarded for bearing the risk of holding stocks? As displayed in Table 1, trailing returns for stocks haven’t come close to earning the excess returns that we’ve all come to expect, even after stocks worldwide doubled from the early March 2009 lows during the Global Financial Crisis! We’ll save an exploration for how the Fundamental Index® concept radically reshapes this picture for another time.

Where is the wealth creation implied by the Ibbotson data? Stock market investors took the risk—riding out every bubble, every crash, every spectacular bankruptcy and bear market, over a 30-year stretch. How much were they compensated for the blood, sweat, and tears spilled with all this volatility? A measly 53 basis points per annum! Indeed, investors who have incurred the ups and downs over the past decade have lost money compared to what they could have earned from long-term government bonds. They’ve paid for the privilege of incurring stomach-churning risk. Not only did Treasury bond investors sleep better, they ate better too!

A 30-year stock market excess return of approximately zero is a huge disappointment to the legions of “stocks at any price” long-term investors. But it’s not the first extended drought. From 1803 to 1857,5 U.S. equities struggled; the stock investor would have received a third of the ending wealth of the bond investor. Stocks managed to break even only in 1871. Most observers would be shocked to learn there was ever a 68-year stretch of stock market underperformance. After a 72-year bull market from 1857 through 1929, another dry spell ensued. From 1929 through 1949, stocks failed to match bonds, the only long-term shortfall in the Ibbotson time sample. Perhaps it was the extraordinary period of history—The Great Depression and World War II—and the spectacular aftermath from 1950–1999, that lulled recent investors into a false sense of security regarding long-term equity performance.6

The Odds

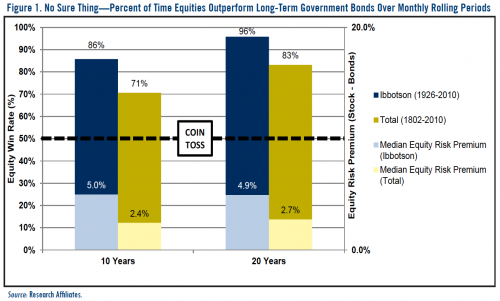

Fortunately for the capital markets and equity investors, an examination of history shows that, yes, stocks have a high tendency to outperform government bonds over 10-year and 20-year periods. Figure 1 illustrates rolling 10- and 20-year “win rates” for equities versus government bonds. We break the data into Ibbotson (1926–2010) and Total (1802–2010). The Ibbotson timeframe confirms investor behavior in the 30 years since Ibbotson and Sinquefield published their groundbreaking study.7 For the vast majority of periods—86% for 10 years and 96% for 20 years—equities outperform bonds. But the longer term data are less convincing. For 10-year periods, equities outperform in 71% of the observations, rising to 83% for 20 years.

A 70% or 80% win rate still offers pretty good odds. In professional basketball, those are average to above-average free throw percentages. But the relatively small probability of failure masks the magnitude of a miss. Just as a single missed free throw can cost a basketball championship, so too can an equity “miss” lead to drastic consequences, as the past 10 years have shown. There is no guarantee of superior equity returns, which begs the question: Why does our industry act like there’s one? More important, why take all that risk for a skinny equity premium?

Conclusion

We aren’t saying that we should expect bonds to beat stocks over the next 10 or 20 years. Rather, this brief history lesson illuminates that the much-vaunted 4–5% risk premium for stocks is unreliable and a dangerous assumption on which to make our future plans. In our view, a more normal economic environment would suggest 2–3%, which is the historic risk premium absent the rise in valuation multiples in the past 30 years. But these are not normal times. Today’s low starting yields, combined with the prospective challenges from our addiction to debt-financed consumption and aging population, would put us closer to 1%.

It would be foolish to act as if the past 200 years is fully representative of the future. For one thing, the United States was an emerging market for much of that period, with only a handful of industries and an unstable currency. In the past century, we dodged challenges and difficulties that laid waste to the plans of investors in many countries. Nassim Taleb points out that “Black Swans”—unwelcome outliers that exceed the bounds of normalcy—are a recurring phenomenon; the abnormal is, indeed, normal. Our own stock market history is but a single sample of a large and unknowable population of potential outcomes.

Peter Bernstein relentlessly reminded us there are things we can never know, that prosperity and investing success are inherently “risky”; they can disappear in a flash. Uncertainty is always with us. The old adage puts it succinctly: “If you want God to laugh, tell him your plans.” Concentrating the majority of one’s investment portfolio in one investment category, based on an unknowable and fickle long-term equity premium, is a dangerous game of “probability chicken.”

Endnotes

1. Ibbotson® SBBI® 2011 Classic Yearbook: Market Results for Stocks, Bonds, Bills, and Inflation 1926–2010, Morningstar.

2. For much of this section, we rely on the data that Peter Bernstein and I assembled for “What Risk Premium is ‘Normal’?” Financial Analysts Journal, March/April 2002. We are indebted to many sources for this data, ranging

from Ibbotson Associates, the Cowles Commission, Bill Schwert of Rochester University, and Bob Shiller of Yale. For the full roster of sources, see the FAJ paper.

3. See Arnott and Bernstein (2002).

4. See Peter Bernstein, “What Rate of Return Can You Reasonably Expect… or What Can the Long Run Tell Us about the Short Run?” Financial Analysts Journal, March/April 1997.

5. 20-year bonds were used whenever possible but the longest maturities tended to be 10 years for much of the nineteenth century. Also, in the 1840s, there was a brief span with no government debt (we should be so lucky!),

hence no government bonds. Under these circumstances, the equivalent to today’s Government Sponsored Enterprises, railway and canal bonds, were used as these projects typically had the tacit support of the government.

6. For more on this, see Robert Arnott, “Bonds: Why Bother?” Journal of Indexes, May/June 2009.

7. Roger G. Ibbotson and Rex A. Sinquefield, “Stocks, Bonds, Bills and Inflation: Year-by-Year Historical Returns (1926–1974),” Journal of Business, January 1976.

©2011 Research Affiliates, LLC. The material contained in this document is for general information purposes only. It relates only to a hypothetical model of past performance of the Fundamental Index® strategy itself, and not to any asset management products based on this index. No allowance has been made for trading costs or management fees which would reduce investment performance. Actual results may differ. This material is not intended as an offer or a solicitation for the purchase and/or sale of any security or financial instrument, nor is it advice or a recommendation to enter into any transaction. This material is based on information that is considered to be reliable, but Research Affiliates® and its related entities (collectively “RA”) make this information available on an “as is” basis and make no warranties, express or implied regarding the accuracy of the information contained herein, for any particular purpose. RA is not responsible for any errors or omissions or for results obtained from the use of this information. Nothing contained in this material is intended to constitute legal, tax, securities, financial or investment advice, nor an opinion regarding the appropriateness of any investment. The general information contained in this material should not be acted upon without obtaining specific legal, tax or investment advice from a licensed professional. Indexes are not managed investment products, and, as such cannot be invested in directly. Returns represent back-tested performance based on rules used in the creation of the index, are not a guarantee of future performance and are not indicative of any specific investment. Research Affiliates, LLC, is an investment adviser registered under the Investment Advisors Act of 1940 with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC).

Russell Investment Group is the source and owner of the Russell Index data contained or reflected in this material and all trademarks and copyrights related thereto. The presentation may contain confidential information and unauthorized use, disclosure, copying, dissemination, or redistribution is strictly prohibited. This is a presentation of RA. Russell Investment Group is not responsible for the formatting or configuration of this material or for any inaccuracy in RA’s presentation thereof.

The trade names Fundamental Index®, RAFI®, the RAFI logo, and the Research Affiliates® corporate name and logo are registered trademarks and are the exclusive intellectual property of RA. Any use of these trade names and logos without the prior written permission of RA is expressly prohibited. RA reserves the right to take any and all necessary action to preserve all of its rights, title and interest in and to these marks. Fundamental Index® concept, the non-capitalization method for creating and weighting of an index of securities, is patented and patent-pending proprietary intellectual property of RA. (US Patent No. 7,620,577; 7,747,502; and 7,792,719; Patent Pending Publ. Nos. US-2007-0055598-A1, US-2008-0288416-A1, US-2010-0191628, US-2010-0262563, WO 2005/076812, WO 2007/078399 A2, WO 2008/118372,EPN 1733352, and HK1099110).

The views and opinions expressed are those of the author and not necessarily those of Research Affiliates, LLC. The opinions are subject to change without notice.

Copyright © Research Affiliates