Based on anecdotal evidence, the daily cost of living in Beijing is now running 20% higher than at this time last year, and for Shanghai it is even higher - about 25-30%. Electricity prices have risen by over 300% and gas prices by some 600% over the last two years in the Shanghai area, and local manufacturers complained to Simon that operating costs are now on par with those in Singapore.

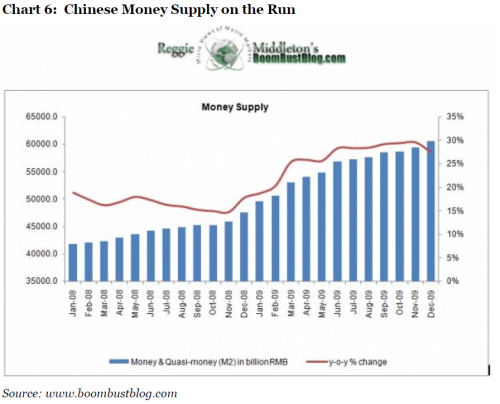

The political leadership in China seems to be focused on food inflation and have recently threatened to instigate price controls on everyday goods; however, I suspect that the source of inflation is to be found in the extremely lax monetary policy of recent years (see chart 6). According to one source, Chinese money supply (as measured by M2) has expanded by a whopping 54% over the past 2 years alone2. It now stands at $10.1 trillion against $8.6 trillion in the US. Meanwhile, China’s monetary base stands at $2.36 trillion versus $1.96 trillion in the US3. Given the fact that the Chinese economy is still only about one-third the size of the US economy, one wonders whether the Chinese leaders took their eyes off the ball and now face an almighty battle to get inflation under control again.

# 7: Civil unrest

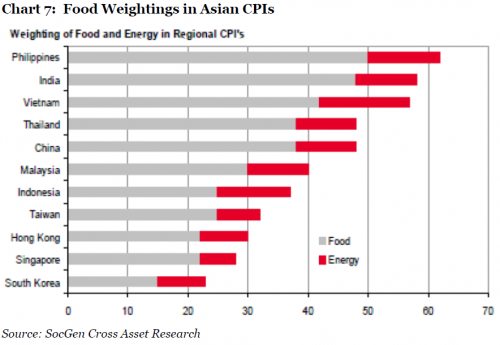

Rising food prices are not only a Chinese problem, though. Across Asia (as

well as in Africa and Latin America) food accounts for a much bigger share of disposable income than what we are accustomed to in Europe and North America (see chart 7); hence the effect on overall consumer price inflation in emerging economies from rising food prices can be massive. We witnessed widespread riots in Asia in the summer of 2008 as a result of rising food prices. Should food prices continue to rise from current levels, civil unrest will almost certainly ensue to the detriment of the local economy and stock markets. That is our risk factor # 7.

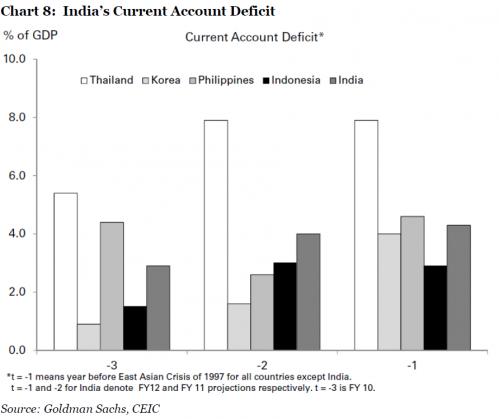

# 8: Is India in trouble?

As one of the countries most prone to political unrest, India faces the added challenge of an escalating current account deficit. Hence we ask ourselves: Is India an accident waiting to happen? (risk factor # 8). At the moment, with strong capital flows into virtually all corners of emerging markets, India is finding it relatively easy to finance its external deficits but, as we have learned from experience, international capital flows are fickle at the best of times. Should investor appetite for emerging markets wane – and it will at some point – India could suddenly find itself in a situation not dissimilar to what Thailand, Indonesia, Korea and the Philippines all faced in the late 1990s (see chart 8).

# 9: European sovereign risk

Moving our attention swiftly to risk factor # 9 – European contagion and solvency risk – I do worry if the extent of the current crisis has fully dawned on our political leaders, who continue to act as if they are dealing with a liquidity crisis – not a solvency crisis. In my opinion, we passed the point a long time ago where the crisis could be solved by writing a €85 billion cheque.

I have written extensively about this particular issue in the past, and shall therefore resist the temptation to repeat myself. Suffice to say that the only way Ireland and Greece (and soon to come Portugal) can ever hope to pay back the bailout loans granted to them is through strong economic growth, but that is a pie in the sky as long as the underlying problems are not addressed. They will eventually have to bite the bullet; it is just a shame that so much wealth has to be destroyed before they get it right.

Maybe our leaders should look north towards Reykjavik. It is remarkable how the Icelandic economy has recovered following its demise in 2008-09. Iceland did what no other European country has been prepared to do – they let the banking sector go bust. I know Iceland is a small country and hence the contagion risk is less of an issue, but perhaps we should learn from that.

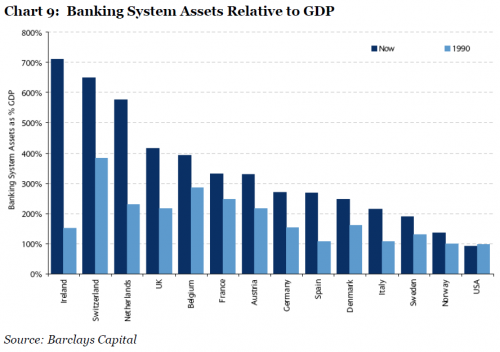

But let’s not kid ourselves. When many European countries make handsome contributions to the Greek and Irish bailout packages, it is not because we are concerned about not being able to visit the beaches of Greece next summer or that the famous Guinness beer will suddenly run dry. No, over the years, we have allowed our banking system in Europe to inflate their balance sheets to a point where contagion risk became a clear and present danger. Take a look at chart 9 and in particular at the size of the US banking system compared to that of most European countries.

# 10: Refinancing needs

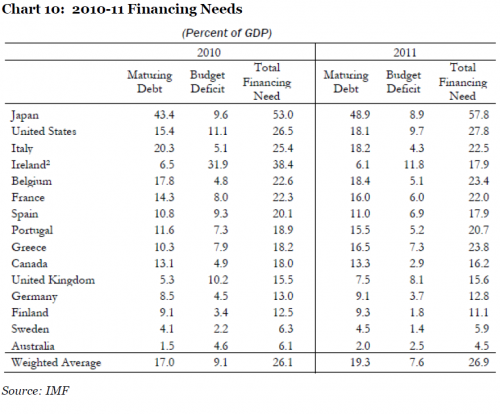

However, from a risk point of view, Spain is the main worry – at least for now. According to the IMF, Spain’s gross financing needs for 2011 approach €200 billion – about 18% of GDP (see chart 10). In addition to that, Spanish banks need to roll a similar amount in 2011-12. This massive refinancing programme (# 10) can only be accomplished if Spain manages to maintain its credibility in international markets because, unlike Japan, financing it domestically is not an option.

Refinancing existing debt is a mammoth task over the next 12 months, not just in Spain but across the world with approximately $10 trillion being up for rollovers globally4. This programme poses the biggest risk to my benign outlook for bond yields and needs to be watched carefully in terms of investor appetite.

#11: Monetary tightening

Risk factor # 11 on my list represents another potential fallout from the credit crisis – I call it premature withdrawal of monetary support. Over the last few weeks we have witnessed the effects of approximately SEK 300 billion of crisis loans being withdrawn in the Swedish market. Short term interest rates and mortgage rates shot up instantly as a result. Sweden is amongst the healthier nations in Europe. Imagine what will happen in

4 Source: Daily Telegraph

countries such as Ireland, Portugal, Spain and Greece, should liquidity facilities be pulled prematurely.

To give you an idea of their predicament, borrowers from Greece, Portugal and Ireland (their combined GDP account for just over half that of Spain’s) took 61% of all loans provided by the ECB last month, up from 51% the previous month. A premature withdrawal of liquidity could have catastrophic consequences for those countries. Over the past few days the crisis appears to have eased off just a little bit - at least enough for the extreme scenarios laid out by some commentators suddenly to look less likely in the short term; however, the crisis is clearly not over yet. The risk is that the ECB, encouraged by the somewhat better tone, begins to drain larger amounts of liquidity from the markets.