Wharton's Professor Jeremy Siegel, the author of Stocks for the Long Run, used historical data (a) to demonstrate that there had never been a long period when stocks didn't outperform cash, bonds and inflation, and thus (b) to argue that most people of average risk tolerance should have roughly 100% of their capital in the stock market. But Siegel, like many laymen, failed to pursue the

most critical line of inquiry. The right question to ask in the late 1990s wasn't, "What has been the normal performance of stocks?" but rather "What has been the normal performance of stocks if purchased when the average p/e ratio is 33?"

Many investors were seduced by the performance of stocks in the late 1990s by the promise of wealth and a secure retirement, and by the meshing of equity participation with the allure of the technology, media and telecom industries. The results are well known: the first three-year decline for stocks since the Great Depression; a peak-to-trough decline of 51% for the S&P 500; massive losses for tech investors; shrunken 401-k accounts; and general disillusionment with stocks.

Basically, I think equity investors had their hearts broken, as happens from time to time in the investment world. The promise of easy money turned out to be empty – as usual – and investors who had adopted overblown expectations promised "never again." A good economy, low interest rates and resurgent general psychology brought stocks back between 2002 and 2007, but just to their 2000 peak. Versus the 11% prospective return they were sure of in 1999, by 2003 many investors expected only 6-7% from stocks (despite the fact that they were now much cheaper). With the bloom off the rose, people looked elsewhere – to private equity, real estate, hedge funds and mortgage backed securities, for example – for the next solution. I didn't hear any investors say, "We don't have enough stocks." Their glory truly had faded.

But having recovered to their previous high, stocks were buffeted again in the credit crisis. They fell 58% from their 2007 peak to their 2009 trough. Stocks weren't singled out for punishment; non-government bonds, real estate, mortgage securities and private equity all shared the pain as panic and loss of confidence were everywhere.

With the panic now gone, stocks have recovered, but only about half their 2007-09 losses. The S&P 500 stands at a level that was first reached in 1998, meaning over the last twelve years, the average stockholder's paltry return of less than a percent a year came entirely from dividends. People talk about the "lost decade in equities," and still no one seems to feel he owns too few stocks.

A Brief History of Bonds

The recent history of bonds requires less telling. Bonds were the bedrock of investment portfolios in the first half of the last century. Along with Treasurys, utilities and corporates, business was brisk in railroad and streetcar bonds. Graham and Dodd's classic, Security Analysis, devoted more than 200 pages to "fixed-value investments" including preferred stock, of which next to nothing is heard today.

The story of bonds in the last sixty years is the mirror opposite of what happened to stocks. First bonds wilted as stocks monopolized the spotlight in the 1950s and '60s, and at the end of 1969, First National City Bank's weekly summary of bond data died with the heading "The Last Issue" boxed in black. Bonds were decimated in the high-interest-rate environment of the '70s, and even though interest rates declined steadily during the '80s and '90s, bonds didn't have a prayer of standing up to equities' dramatic gains.

By the time the late 1990s rolled around, any investment in bonds rather than stocks felt like an anchor restraining performance. I chaired the investment committee of a charity and watched as a sister organization in another city – which had suffered for years with an 80:20 bond/stock mix – shifted its allocation to 0:100. I imagined a typical institutional investor saying the following:

We have a little money in bonds. I can't tell you why. It's an historical accident. My predecessor created it, but his reasons are lost in the past. Now our fixed income allocation is under review for reduction.

Even though interest in stocks remained low in the current decade, little money flowed to high grade bonds. The continued decline in bonds' popularity was fed, among other things, by the decision on the part of the Greenspan Fed to keep interest rates low to stimulate the economy and combat exogenous shocks (like the Y2K scare). With Treasurys and high grade bonds yielding 3- 4%, they didn't do much for institutional investors trying for 8%.

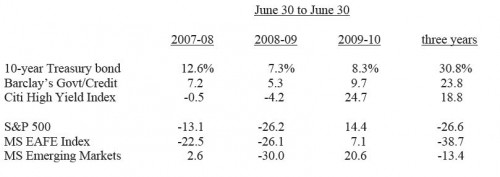

As a result of a process I consider quite standard, bond allocations reached all-time lows at just the time they became needed. Other than cash and gold, Treasurys were the only asset that performed well in 2008. In fact, they benefited from a massive flight to quality. Corporate high grade and high yield bonds suffered along with everything else in 2008, but less than stocks, and they've enjoyed a comparable recovery. Thus bonds have performed much better than stocks since the onset of the crisis in July 2007, as shown on the next page.

Clearly, the recent performance edge of bonds over stocks has been dramatic.

What's Going On Today?

Now, suddenly, investors seem to have awakened to bonds' attractions. This after failing to do so in time for the crisis, when holding bonds would have been of great value. Is this just another case of investors driving while looking in the rearview mirror? And are they shifting from stocks to bonds at just the wrong time?

The headlines are dramatic and the facts are clear. In just the last few weeks, we've seen newspaper stories like these: "Investors Fleeing Stocks with Cash Flow Lure JP Morgan" (Bloomberg, August 16), "Treasury Bears Cave as Bond Yields Keep Tumbling" (The Wall Street Journal, August 16), and "Growing Concern over Bond Bubble" (Financial Times, August 21). Bloomberg reported as follows:

About $33 billion flowed out of funds owning U.S. shares this year . . . About $185 billion was sent to bond funds through July 31, the most on record, according to the Investment Company Institute.

Comments are closed.