This article is a guest contribution by Eric Sprott and David Franklin of Sprott Asset Management.

There’s nothing wrong with throwing a little money at a problem to make it go away. There’s equally nothing wrong with throwing a little borrowed money at a problem to make it disappear, as long as you have the means to pay that borrowed money back.

But what happens if you throw a lot of borrowed money at a problem, and the problem doesn’t go away? If you’ve ever experienced a situation like that you can probably understand how Europe feels right now. It just unleashed a magnificent $1 trillion euro bailout and the market responded with a selloff by the end of the week! So what happened? That money was supposed to make the problem go away, after all. And it was a lot of money. Why did the market respond to it with such disdain?

We believe the market’s reaction is confirming what we have long suspected: that these bailouts provide next to no long-term value. They don’t produce real jobs. They don’t improve productivity. They just prolong the precarious leverage game played by the financial sector, and do so at tremendous cost to taxpayers. "Bailout and Stimulate" has been the rallying call for governments and central banks since the beginning of this financial crisis – and it has certainly had its impact over the last two years, but not the type of impact we need to propel real, sustainable growth. There are three recent, glaring examples of this busted "Bailout and Stimulate" formula in action:

Exhibit A: The United States

From the outset of this financial crisis, the US Government and Federal Reserve have spent prolific amounts of money to save its banks and stimulate its economy. According to Neil Barofsky, special investigator general for the Troubled Asset Relief Program, the United States has now spent approximately $3 trillion on various programs to stem the financial crisis.1 This figure is expected to be updated again in July.

This $3 trillion expenditure includes stimulus programs like ‘cash for clunkers’, the extension of unemployment benefits, infrastructure spending, the "Making Home Affordable" program, as well as the activities of the Federal Reserve. To measure what the fiscal stimulus has actually accomplished we looked to the US Federal budget outlays/receipts to gauge the impact of the stimulus on GDP.

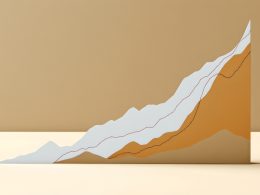

Table A presents current dollar GDP increases year-over-year alongside current dollar budget deficits. Comparing the two in current dollars provides a sense of the hard dollar impact that stimulus spending has had on the economy. As the chart illustrates, the net impact of the stimulus contributions and promises made since 2008 have resulted in a combined budget deficit of close to $2.5 trillion dollars and an incremental net increase in GDP of $200 billion. A $200 billion return for a $2.5 trillion increase in debt represents a terrible return on investment. It implies that the net impact of the stimulus on GDP since 2008 has been a mere 9 cents for every deficit dollar spent. Buying dimes with dollars is bad business, government-funded or not.

Another troubling statistic relates to the cost of job creation for the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (that’s the $787 billion program designed to produce real jobs in the United States). The White House estimates that it takes approximately $92,000 of government spending to create one job in the US. The White House justifies this exorbitant amount by stating that at the current employment level, each job in the US economy generates $105,000 in GDP, thus resulting in good "bang for the (taxpayer) buck".5 Spending $92,000 to generate $105,000 in GDP seems justifiable on the surface. But further digging reveals that the actual cost to save or create one job in the US was $117,933 per job from February to December 2009.6 That’s well over $92,000, and more than the $105,000 "return" each job is supposed to provide in GDP. If this metric is correct, it means the US government is actually suffering a negative return from its job stimulus.

To further convolute the issue, one must also consider that the supposed $105,000 GDP return for each new job doesn’t incorporate the fact that the $92,000 (or $117,933) spent to create it was BORROWED. Why does this aspect of government expenditure never make it into the analysis? Spending $92,000 for a $105,000 pop in GDP represents bad logic when that $92,000 isn’t yours to spend. If we incorporate the interest costs required to borrow the $92,000, are we really producing value or just digging a deeper hole?

Numerical discrepancies aside, the fact remains that GDP is a terrible metric to measure the return of a job program. GDP is technically the value of all finished goods and services produced in an economy. From a business perspective, GDP is akin to revenue, which isn’t an asset, and is different from ‘earnings’ or ‘profits’. Businesses don’t hire additional workers for their marginal increase to ‘revenue’ – they hire to increase their marginal ‘profit’. The White House approach to job stimulus will maximize spending, not profit. Rather than maximize spending, why not maximize actual employment by finding a way to produce a job for less than $92,000? Surely some of the fifteen million unemployed workers in the US would appreciate some help in that area.7