by Neuberger Berman Fixed Income Investment Strategy Committee

You might be surprised to learn that European high yield bonds were the top-performing credit market over the 10-year period ended August 31. In all honesty, some of us were, too. The development of the asset class in the years following the financial crisis, however, is impossible to ignore. We think European high yield bonds have earned a place as part of an investor’s strategic allocation, offering an attractive diversification opportunity marked by high hedge-adjusted yields, relatively low duration and robust market fundamentals in an improving macro environment.

Surveying the tight valuations across the fixed income investment landscape, it’s hard to shake the feeling that the asset class is vulnerable. That said, it’s just as hard to pinpoint how and when that vulnerability may manifest itself given the durability of the current credit cycle. As we discussed in our 2Q17 Fixed Income Investment Outlook, the below-average economic recovery in the years following the Great Recession seemingly has suppressed the development of excesses across the economy and financial markets, extending the business and credit cycles. Meanwhile, interest rates globally remain anchored at very low levels even as the U.S. Federal Reserve continues along its cautious policy normalization path and the European Central Bank prepares to wind down its own stimulus efforts.

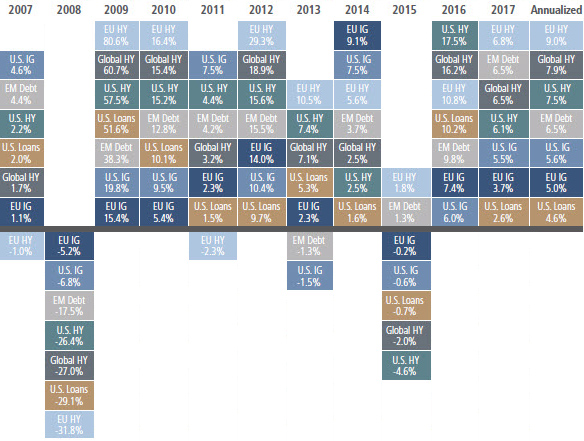

So the search for yield persists, as does the compression of spreads on assets able to deliver it. We continue to see strong flows from our clients into opportunistic, go-anywhere mandates across public and private fixed income markets, as well as into more targeted opportunities in areas like emerging markets debt and high yield. One source of yield that perhaps is less universally recognized is European high yield debt, despite a 10-year annualized return of 9.0% on a hedged U.S. dollar basis as of August 31, 2017, which ranks it number one among credit categories globally, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. European High Yield Has Led Global Credit over the Past 10 Years

Annual hedged returns in U.S. dollars as of August 31, 2017

Source: Bank of America Merrill Lynch.

Note: U.S. HY = BofA ML U.S. High Yield Master II; EU HY = BofA ML European Currency High Yield; EM Debt = BofA ML EM Corporate Plus; U.S. IG = BofA ML U.S. Corporate Master; EU IG = BofA ML Pan Europe Large Cap Corp; Global HY = BofA ML Global High Yield; U.S. Loans = S&P/LSTA Leveraged Loans.

A Globalizing High Yield Market

For some time, exposure to high yield bonds meant, for all intents and purposes, exposure to U.S. high yield bonds, with non-investment grade offerings issued in other domiciles too small to play a role in the allocation decisions of most investors; in fact, as recently as 10 years ago U.S. high yield accounted for approximately 90% of the global high yield benchmark. Once exclusively the provenance of so-called “fallen angels” (i.e., bonds stripped of their investment grade ratings), the high yield market in the U.S. found its footing in the 1980s and subsequently has matured into a key strategic allocation for investors of all types, offering a compelling combination of risk, return and correlation benefits for the investor and financing flexibility for the issuer. Despite the runaway success in the U.S., however, high yield bonds were slow to catch on elsewhere, including in Europe, where corporate financing was dominated by banks and there was little to suggest the growth in issuance that would eventually emerge.

In fact, Neuberger Berman as an organization was among those guilty of underestimating the potential of European high yield bonds. For some time, we didn’t think European high yield was a durable business worth our investment in time, money and resources. Attitudes—both within Neuberger and the investment management industry at large—began to change in the aftermath of the financial crisis in 2007–09, however, and since 2008 the European high yield market has grown significantly in size and broadened in terms of both issuers and industries represented. Outstanding high yield debt spiked to well over $400 billion from less than $100 billion in 2005 and now represents approximately 20% of the global high yield market. Issuers run the gamut from household names like Fiat, Telecom Italia and Nokia to smaller European companies tapping debt markets for the first time. Even non-European companies are looking to take advantage of the attractive European market; for example, Netflix—which is headquartered in Los Gatos, California—in April issued €1.3 billion in euro-denominated high yield debt to finance its production of original content.

The post-crisis growth of the European high yield bond market has been fueled primarily by two factors:

- Fallen angels: The global financial crisis and subsequent sovereign debt crisis wreaked havoc on the health of Europe’s corporations—particularly those in peripheral Europe—costing a number of them their investment grade ratings and pushing them into high yield indexes.

- Bank disintermediation: In contrast with the United States, where corporations meet the vast majority of their financing needs via the capital markets, European companies have long looked to banks as their primary source of funding. This has been evolving in recent years, however, as post-crisis regulatory developments have encouraged banks to deleverage their balance sheets while rock bottom interest rates have made the bond markets more appealing to borrowers—both existing high yield issuers and new entrants into the space.

Though the fallen angel story has played out for this cycle, we expect bank disintermediation to persist in the coming years and fuel the continued expansion of the European high yield market. Also, it’s worth noting that as the debate over tax reform again heats up in the U.S., elimination of the interest expense tax deduction is among the proposals on the table. Were the deduction to be eliminated from the tax code, U.S. companies with offshore affiliates would be incented to borrow in those jurisdictions where deductibility remained, perhaps providing further supply to European credit markets.

European High Yield as a Complement to U.S. High Yield Exposure

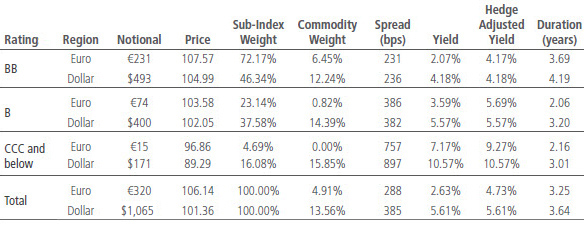

Figure 2 compares the European high yield market (as represented by Bank of America Merrill Lynch European Currency High Yield Index) with the U.S. market (Bank of America Merrill Lynch U.S. HY Master II Index). While headline yields are higher in the U.S. market, adjusting yields for hedging costs to the U.S. dollar investor tells a different story. The European high yield universe offers better credit quality than the U.S. market, with more than 70% of issuers carrying a BB rating compared to around 46% in the U.S. European management teams have been conservative for the most part, taking advantage of the extended period of low interest rates to refinance with longer-dated, cheaper debt. The growth of these conservatively financed companies is now being supported by accelerating economic growth in Europe; the latest reading on GDP growth for the region came in at 2.3% annualized for the second quarter, its fastest pace since 2011. While the unexpectedly strong euro has kept inflation tracking below target, the European Central Bank has begun to discuss the tapering of its bond-buying program, though its benchmark rate is likely to remain at zero for some time. After spiking in the aftermath of the financial crisis, default rates have plummeted in recent years, and we believe they will remain near their historical lows for the foreseeable future, making European high yield a source of stable income in this volatile global environment.

Figure 2. High Yield Market Characteristics: U.S. versus Europe

As of August 31, 2017

Source: Bloomberg, Bank of America Merrill Lynch.

Note: Assumes 210 basis point dollar/euro annual hedging gain. Euro = BofA ML European Currency High Yield; Dollar = BofA ML U.S. High Yield Master II.

Duration is another number that jumps out in Figure 2. European high yield offers lower duration across rating cohorts, thanks to their shorter maturities combined with higher coupons. With less sensitivity to interest rates, European high yield issues may outperform their U.S. brethren in a rising-rate environment that many expect. Both, meanwhile, have fared better than investment grade paper during periods of rising rates given the cushion of wider credit spreads.

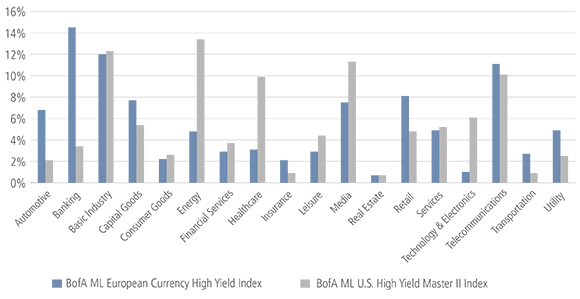

Perhaps the strongest argument in favor of adding European high yield as a strategic exposure is the diversification benefits it can provide. This is not simply about adding 600-plus issues to your investment universe—it’s about access to an opportunity set that bears many of the same hallmarks of the U.S. high yield market while offering a different set of exposures, as shown in Figure 3. Though correlation between the European and U.S. markets tends to be high on average (90% for the 10 years ended August 31), sector diversification allows the markets to decouple at times; for example, European high yield investors in 2015 benefitted greatly from the index’s limited share of energy issuers.

Figure 3. European High Yield Markets Add Meaningful Sector Diversification

As of August 31, 2017

Source: Bank of America Merrill Lynch.

Conclusion

Solid growth in the marketplace combined with superior performance has distinguished European high yield as an asset class worthy of consideration by most investors. Though valuations in the European high yield credit market may seem rich currently, as they are throughout the fixed income complex, we believe they fairly compensate investors for the market’s very low default risk and that the asset class represents a source of stable income in a volatile global environment.

A Look at Corporate Hybrids

Another oft-overlooked corner of the fixed income space that has exploded in size and scope since the financial crisis is the corporate hybrid market. First introduced in 2005, corporate hybrid securities now constitute a $150 billion market. Hybrids are most denominated in euros and predominantly carry an investment grade rating, though one that is several notches below an issuer’s senior paper. Hybrid issuance is dominated by European companies in general and utilities and telecoms in particular. We believe the market is poised to grow at a rate of around $20–25 billion a year, supported by a pickup in mergers and acquisitions activity on the Continent along with issuer refinancing needs.

As the name suggests, a corporate hybrid security is debt capital that also has some characteristics of equity and as such can be considered 50% “equity content” by the ratings agencies when structured correctly. For the issuer, this means that hybrid capital can be raised without diluting equity shareholders (because it is really debt) while at the same time protecting its credit rating (because the agencies count it partly as equity and partly as debt). For the investor, it means hybrids fall below other forms of debt in the capital structure and thus pay a higher coupon, though an issuer can stop paying those coupons without defaulting, as it can with equity dividends.

Another characteristic hybrid securities share with equities is that they are either extremely long-dated or perpetual in maturity; final maturities on these issues typically range from 60 years to infinity, though in practice these bonds are priced as if they will be called on their first call date, which is usually five or 10 years post-issuance. This structure has some investors concerned about duration and call risk posed by hybrids in a rising interest-rate environment. Namely, what if issuers look at the rising cost of capital and decide to leave outstanding the hybrids they sold during a period of exceptionally low rates, effectively causing a large portion of this market to be valued as if they were relatively low-yielding perpetual bonds?

Given the overwhelming incentives that issuers have to respect their first call dates, we think these fears are overblown. The vast majority of outstanding hybrids are structured such that they reset every five years in a manner that better aligns them with prevailing market rates, and they also are subject to a number of “step-ups” that further increase the coupon payments on uncalled securities. Further, ratings agencies have indicated that hybrids going uncalled at their first call date lose their “equity content,” effectively transforming them into expensive debt from the issuer’s perspective. In short, the prospect of corporate hybrids failing to be called remains remote—regardless of what happens to interest rates.

Some evidence of the market’s durability was seen in late June and early July of 2017. Though German bund yields leapt by almost 40 basis points during this time, hybrids performed relatively well and very much in line with the market’s option-adjusted duration of 4.3 years (a full 1.6 years shorter than that of the Bloomberg Barclays Euro Credit Index).

We do still expect the low-yield environment to encourage more investors to rotate out of senior bonds and into hybrids. This will be good news for existing hybrid investors. It is also true that the tightening of monetary policy in the euro zone will involve a gradual unwinding of the ECB’s asset purchase program, which may involve selling senior debt back into the open market. We expect some gentle widening in senior spreads as that tapering comes into effect, but nothing dramatic: inflation remains muted, the ECB continues to purchase greater volumes of corporate bonds than it initially expected to, and the growth and risk background in the euro zone is increasingly benign.

Copyright © Neuberger Berman