by The Algonquin Team, Algonquin Capital

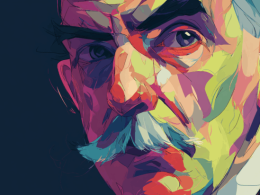

Using volatility as a measure of risk is nuts.

Charlie Munger

The future is full of possibilities, some good some bad. Risk comes from not knowing which of them will come to pass. Given it’s impossible to imagine and consider every potential outcome, we focus our energy on the most likely ones.

In market speak, the ‘probable’ range of outcomes is expressed as volatility. A useful metric that fits nicely into models and gives an indication of the ups and downs one can expect to endure. The trouble investors run into is when they use it as a proxy for risk.

While investment risks are both broad and personal, they typically fall into the categories of losing money or not making enough of it. Both of which are more a function of valuation and sound fundamentals rather than of mercurial markets.

The best way to protect and grow capital is to buy quality assets at attractive prices. Given its propensity to spike after significant equity declines, high volatility often indicates the opportunity to do just that. To ‘be greedy when others are fearful.’

Conversely, periods of stability can lead to an underestimation of uncertainty in the market and the odds of the ‘improbable’ occurring. Often when it is prudent to be ‘fearful when others are greedy.’

So how should investors use and interpret volatility?

The first step is in recognizing what volatility is and is not. It is not a substitute for risk but is one measure of a particular type of risk. For those with short-term horizons or trading with leverage, it is a real concern, and substantial variations in value need careful management.

But for the majority of us, portfolio fluctuations are tolerable as long as the overall trend is up. After all, one would prefer an investment that generates positive but erratic returns, rather than one that consistently and steadily loses money.

Perhaps then volatility’s appropriate value is as a measure of fear, or the lack thereof. As a gauge of investor sentiment, it can provide both an indication of near-term threats and longer-term opportunities. The natural question is whether the level of complacency or fear is warranted. When valuations and fundamentals do not support the ‘wisdom of the crowd,’ it might be time to be either prudent or aggressive.

It’s not that volatility is not a useful and valuable risk metric. We are not ones to throw the baby out with the bath water. But taken in isolation, the picture is imperfect and incomplete. After all, quantitative metrics can help us understand risk, not define it.

Copyright © Algonquin Capital