by James Redpath, CFA, Mawer Investment Management, via The Art of Boring Blog

In case you missed it, Argentina recently surprised the world with an amazing spectacle.

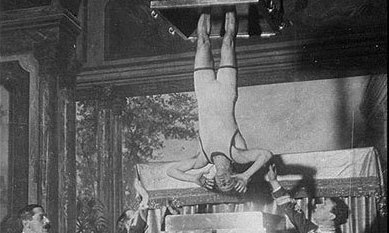

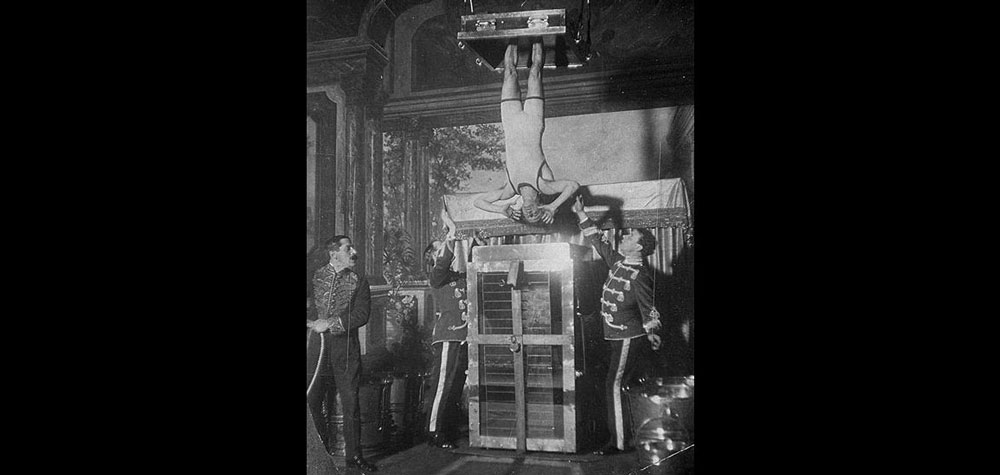

Reminiscent of master escape artist Harry Houdini—who made a small fortune performing upside down and bound in heavily shackled circumstances—Argentina issued a $2.75 billion century bond in U.S. dollars at an interest rate of 7.125%.1 This means that the Argentinian government doesn’t have to pay investors back until the year 2117. Looking at it a different way, it matures in about 1.4 human generations! They did this not for fame or glory, but to help raise money to fund the government’s fiscal deficit. This is a truly remarkable feat given Argentina’s overwhelming history of defaults.

On the spectrum of reliable debtors, Argentina is about as bad as you can get. Argentina has defaulted many times in its 200 year history including: 1951, 1956, 1982, 1989, 2001, and its “selective default” in 2014. Indeed, their 2001 default on $80 billion of U.S. dollar-denominated bonds was the largest sovereign default at the time. Argentina has now spent 75 out of the last 200 years in default status.2

That in itself is a marvel and somewhat Houdini-esque, but consider this: while Houdini made an elephant vanish, Argentina once made an entire ship disappear. The country’s 2001 default included owing a $1 billion debt to U.S.-based hedge fund NML Capital and they seized The Libertad—one of Argentina’s premiere naval ships—from a port in Ghana as partial repayment.3

And just like that—poof!—The Libertad was gone. Magic.

Given Argentina’s notorious credit status, the maturity profile is particularly brash. 100 years is a long time, especially for a country that is rated as “junk” at all the major credit rating agencies. Who knows if a 7.125% coupon in U.S. dollars will be good value or too expensive in a generation or two?

Moreover, it does not seem that bondholders are getting paid much extra for holding these bonds to maturity—the difference between the interest rate of a 30 year bond and a 100 year bond for Argentina (in U.S. dollars) is less than 1%. That’s little additional compensation for the extra term (a mere 70 years!). Seems like a pretty good deal for Argentina. Not so good for bondholders.

Still, investors bought this bond for a reason—they believe they can make money off it. It doesn’t really matter if Argentina manages to deliver the goods in 100 years or not because the vast majority of investors have no plans of holding it until maturity. In terms of strategy, whether bondholders hold it for 10 years or 50, they are buying the bond because they have faith that bond prices will rally as the country’s political and economic circumstances improve. They seek to make money off trading. Presumably, they believe they can simply get rid of the bonds before anything goes south.

Another likely reason why some investors bought this bond is duration. Very long duration bonds are vehicles through which investors can bet on interest rate moves in an amplified manner. This is because the longer the duration, the more sensitive the price of the bond is to changes in yield. For example, let’s say that you think the yield will fall from 7% to 6% overnight on each of the following bonds: 5 year, 10 year and 100 year. In a 5 year bond, your return through this period could be about 4%. However, the return of holding a 10 year bond might be double that, at about 8%. And the return of a 100 year bond? Huge.

Do we see these reasons as compelling enough to own 100 year Argentinian bonds in our Global Bond Fund? Not so much. There’s not a lot of magic in these bonds for our team.

Don’t Cry for Me, Argentina

Of course, this is only the investor’s angle… what about Argentina? Are these bonds good or bad for the country?

It’s hard to say. On the one hand, the interest rate Argentina will have to pay on these bonds is low based on history. It seems like a good deal for them. On the other hand, the bond is a priced in U.S. dollars, which is a different currency than the one that is primarily used domestically, the Argentinian peso. This could be a problem in the future. While Argentina collects its revenues in the Argentinian peso, it is forced to service interest and principle payments in U.S. dollars.

When countries issue debt that is denominated in a currency that is different from their own, they can create a risky mismatch. Argentina can’t just print money in U.S. dollars to pay off its debts: Argentinian pesos have to be converted to U.S. dollars first. So if the Peso happens to fall against the U.S. dollar, the cost of repaying their debts can quickly become unmanageable. We’ve seen this play out many times in the past (e.g., the Asian Financial Crisis, Mexico Default).

It would seem that Argentina and investors are both willing to take this risk. For all the history that Argentina has with defaults, investors seem to have brushed that aside. These bonds have traded as high as $3 above the new issue price and were significantly over-subscribed with more than $9.75bn U.S. dollars in orders. Argentina must be pleased. And in issuing these ultra-long bonds, the country now joins the likes of Mexico, Ireland and the U.K. in selling debt that matures in a century.

The reality is that no one really knows how this will play out. Unlike Houdini’s legendary escape acts, the world will have to wait until the maturity date of 2117 to see if Argentina is actually able to pull theirs off. Our team has not suspended disbelief.

1 As reported by Reuters

2 As reported by Bloomberg

3 NPR: Why a Hedge Fund Seized an Argentine Navy Ship in Ghana

![]()

About James Redpath

James Redpath, CFA, is a Portfolio Manager at Mawer Investment Management Ltd., which he joined in 2010. Mr. Redpath is the lead manager of the Mawer Global Bond Fund and co-manager of the Mawer Canadian Bond Fund and the Mawer Canadian Money Market Fund. Learn more

This post was originally published at Mawer Investment Management