by Ben Masters, Third Wave Finance, via Clarity Financial

One of the common side effects of debt-fueled speculation/spending is financialization, and one should immediately look to the growth and prominence of the financial industry (since the 1980s) with alarm, hesitation and concern; how and why is it that an industry that produces no physical product has grown to its current size? After all, the financial industry exists as a non-production-utility — its very purpose is to properly allocate capital and resources to desirable (in-demand) industries; it’s an industry whose very existence relies on the success of other industries. If the financial industry is able to properly allocate capital/resources to desirable industries, it’s rewarded and is able to grow along with those other fundamental industries; and if a misallocation occurs, capital/resources are allocated to (and used up by) unsuccessful industries — those industries then shrink, along with the finance industry and economic growth.

The concern then is that if a general “hollowing out” of production occurs in a country — something that is rarely disputed these days when addressing U.S. industry — this would typically result in a smaller financial industry, not a larger one; yet the explosion of growth in the finance industry since the 1980s has been in stark contrast. Why is this? Put simply, debt-fueled investment speculation and debt-based spending has exploded since the 1980s.

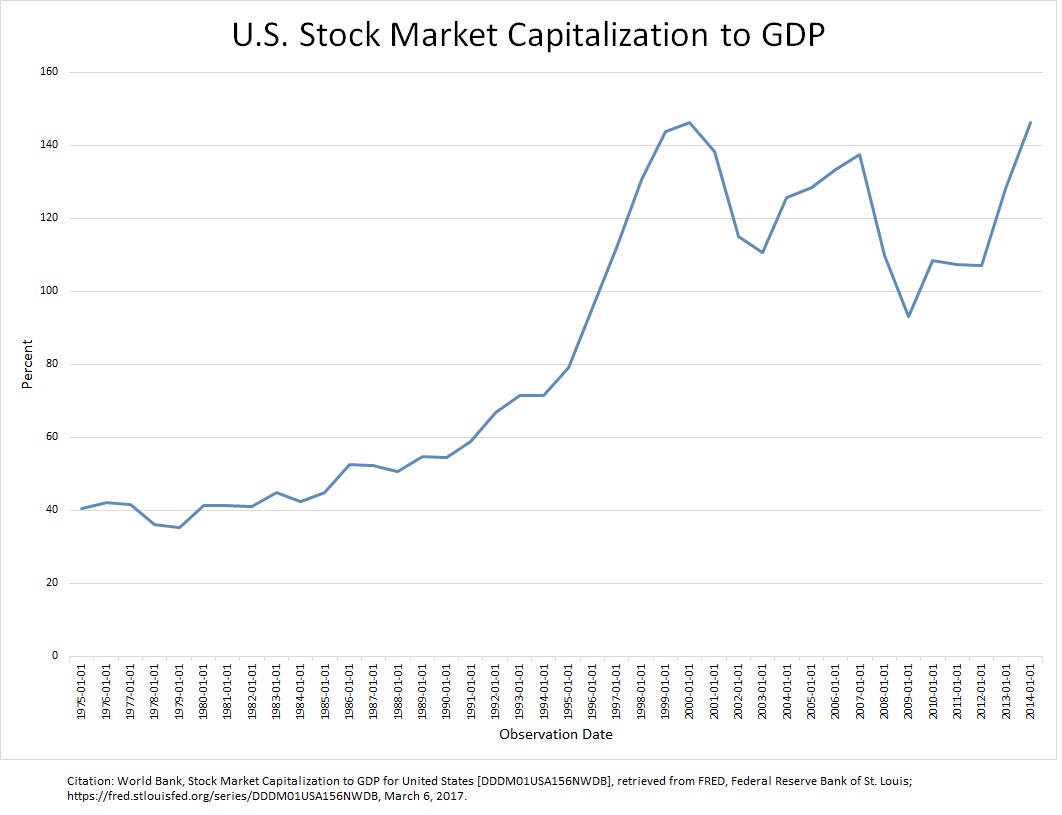

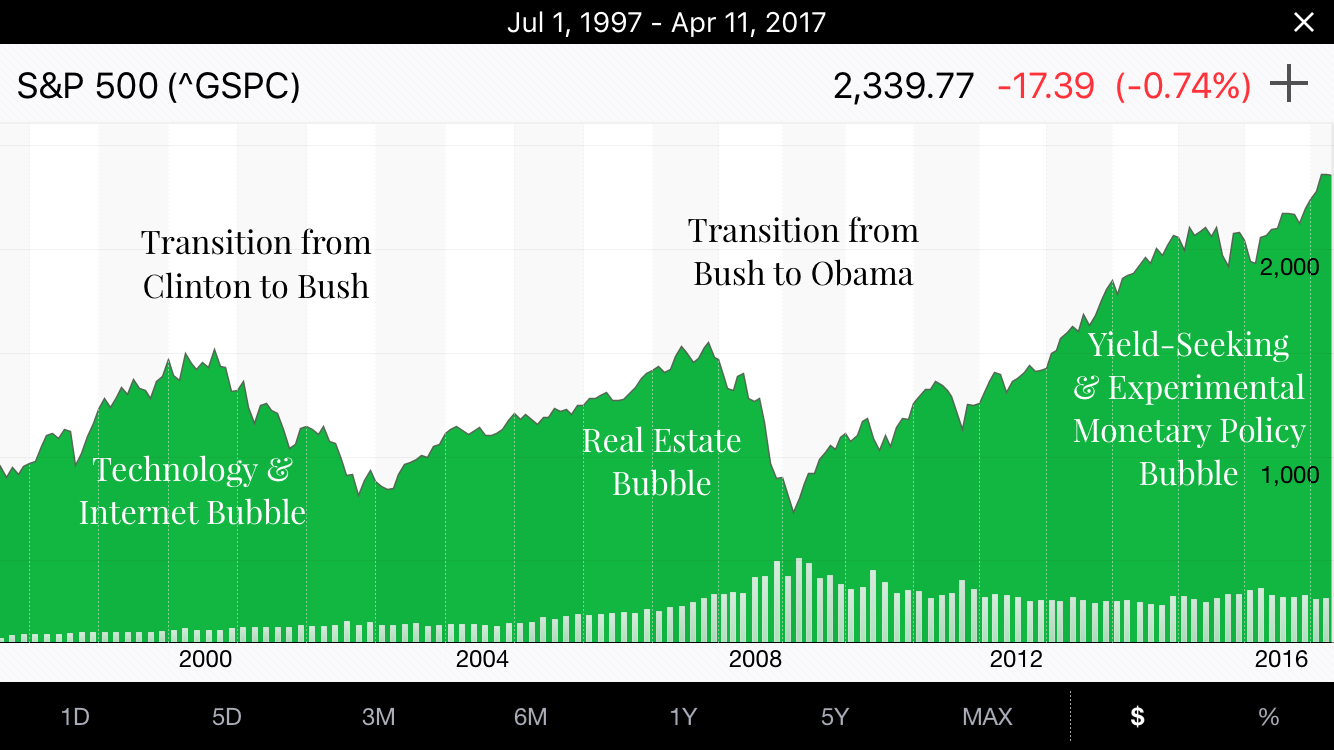

Debt-fueled investment speculation can be seen in this visual of the three instances of the 21st century where long-term returns for stocks have been reduced — each peak fueled by different forms of speculation that ensure low future returns:

Tradable securities far outpacing economic growth…

The three speculative episodes of the 21st century, and dangerous transition periods…

Each of these speculative episodes have been addressed in The Orchestration of Debt-Based Expansions; and the topic of debt-based spending (pursued since the 1980s) has been written about as well, and includes government debt and consumer debt (mortgages, credit cards, student loans, car loans, borrowing to supplement falling incomes, etc.): see Debt Levels, Why does college cost so much?, Why doesn’t anyone earn anything in a bank account anymore?, and Income Stagnation.

The dilemma is that debt temporarily inflates the price of desirable assets (until the point in time where that debt needs to be paid back), and if a majority of the economy has debt that needs to be paid back economic growth is constrained — at some point in time those individuals are paying back loans instead of boosting economic growth through spending. And if the majority of the economy has unproductive debt (debt that has not created an income stream to repay the principal amount borrowed and interest on the debt) then defaults, write-downs, etc. have a punishing affect on the economy and financial system.

For many, that punishing affect is a destruction of investments (which are not the same as wealth… see Fundamental Wealth). Their “assets” evaporate, prices plunge, and they don’t know why… The reason that assets vanish in a market crisis is because debt is always considered an asset by the issuer, yet in reality debt isn’t always an asset for the issuer; there are improper claims of assets — assets that don’t exist (loans that won’t be able to be paid back). In effect, there are claims of assets (and securities issued on those “assets”) that outnumber the actual underlying assets.

It’s the financialization due to debt/leverage/speculation — the adding of layers and complexities — that can lead to a weakening of the market structure; one need only look to Charles Kindleberger’s work Manias, Panics, and Crashes to see how this process has unfolded over and over throughout history.

“Speculative manias gather speed through expansion of money and credit. . .there are many more economic expansions than there are manias. But every mania has been associated with the expansion of credit. In the last hundred or so years the expansion of credit has been almost exclusively through the banks and the financial system.

In boom, entropy in regulation and supervision builds up danger spots that burst into view when the boom levels off.” – Charles Kindleberger

And so financialization — the prominence of the finance industry and the growing dominance of obscure types of investments (many of which are simply more expensive packages of existing investments) — is made plain and clear: since the 1980s, it has grown due to temporary debt-based investment speculation and debt-based spending. And although financialization is temporary (debt constraints eventually cause a readjustment), the real danger is that the temporary misallocation-of-wealth that occurs rewards the financial industry in a boom/bust cycle; wealth and capital that would have been used in other in-demand industries (had productive debt been pursued) is instead concentrated and used up in the financial industry, and when coupled with the ability to influence politics this temporary reward/misallocation can cause a further entrenchment of the undeservedly rewarded industry — a further misallocation of wealth.

Said in 2009 by Jeremy Grantham, co-founder and chief investment strategist of Grantham, Mayo, & Van Otterloo — one of the largest investment companies in the world…

“I’d like to challenge the usefulness — not just of new instruments — but of large tracts of the whole financial industry, much of which is a net drag. Let’s start with the investment management business, because I think intuitively, obviously, you can see that we collectively add nothing. We produce no “widgets”, we shuffle the existing value of all corporations and bonds around, in a cosmic poker game. At the end of each year, the investment community is down by one percent (cough)…the individual is down by two, and aggregate fees have steadily grown. As we grew by ten times from ’89 to ’99 huge economies of scale were existing, but the fees-per-dollar-managed grows — no fee competition at all, contrary to theory. Why? Agency problems, asymmetry of information, the client can’t tell talent from luck or risk taking, and as we add new products (options, futures, CDOs, hedge funds, private equity) aggregate fees rise as a percentage of assets; there becomes a layer of fees and another layer of agents and fees — the more complicated and opaque, the more the client need us. . .

As fees go up by half-a-percent, we reach into the client’s balance sheet, snatch the half-a-percent, and turn it into income; it’s almost magic — capital into income… but we lower the savings rate of our clients (savings and investment rate) by half-a-percent as our fees go up, so we get short term GDP kick from our income, at the expense of lower long-term growth on the part of the system. Similarly with the whole financial system… let us say by 1965 (the best decade we ever had, the ’60s) there was a very financial financial-service arrangement — enough banking, enough letters of credit, to get the job done.

Adequate tools are vital — that’s not the issue. We’re talking the razzmatazz of the last ten or fifteen years… The financial system was 3% of GDP in 1965 — it’s now 7 1/2; this is an extra 4% load that the real economy carries. The financial system overfeeds and slows down the real economy. The first hundred years, up to 1965, the economy was like a battleship, growing at 3.5% a year. Even the great depression bounced off it. After 1965 the GDP (ex-financials) grew at 3.2; after 1982, at 3.1; after 2000, at 2.3; all of these to the end of ’07 (not including the current problems). From society’s point of view this 4% works like looting, or an earthquake — both increase GDP short term, but chew up capital. They might as well be retirees or children — all these extra people in the financial business— but they are much, much more, expensive.

Economists have not studied the optimal size for finance — indeed, a learned journal recently rejected a paper on the grounds that finance does not comment on social utility; that is perhaps why the risks are little.

The underlying problem recently has been touching faith in capitalism, this faith was based on 50 years of a dominant economic theory that was shockingly not based on facts but on unestablished, unprovable, assumptions: “rational expectations” — this has given us efficient markets. So why regulate new instruments, if capitalism and markets are efficient? Or why regulate anything? So Greenspan, Rubens, Summers, and the SEC, happily beat back Brooksley Borne trying to regulate new instruments. But as Keynes knew in 1934, markets are behavioral jungles, racked by changing animal spirits, and by agency problems. Efficient markets assume symmetry of data on all sides. In real life, agents have all the data and the principal clients know little. It’s like taking candy from babies, the more opaque and complicated the new instruments, the easier the ripoff. There is now — at LSE [London School of Economics] — a Centre for the Study of Capital Market Dysfunctionality, started by my former colleague, Paul Woolley, that is even now, attempting an academese, to establish that in the real world condition, agents in finance tend towards getting everything.” — Jeremy Grantham, 5:33 mark of 2009 Buttonwood Gathering

Benjamin Masters a guest contributor to www.RealInvestmentAdvice.com, is the creator, designer, and writer for Third Wave Finance; he has relied on over ten years of financial services industry experience (working as a lead Portfolio Analyst) to develop this educational resource. You can contact Ben via Twitter, Linked-in, or Facebook.