This article is a guest contribution by Tony and Rob Boeckh, Boeckh Investment Letter.

"Let every man divide his money into three parts, and invest a third in land, a third in business, and a third let him keep in reserve."

-Talmud, circa 1200 BC - 500 AD(1)

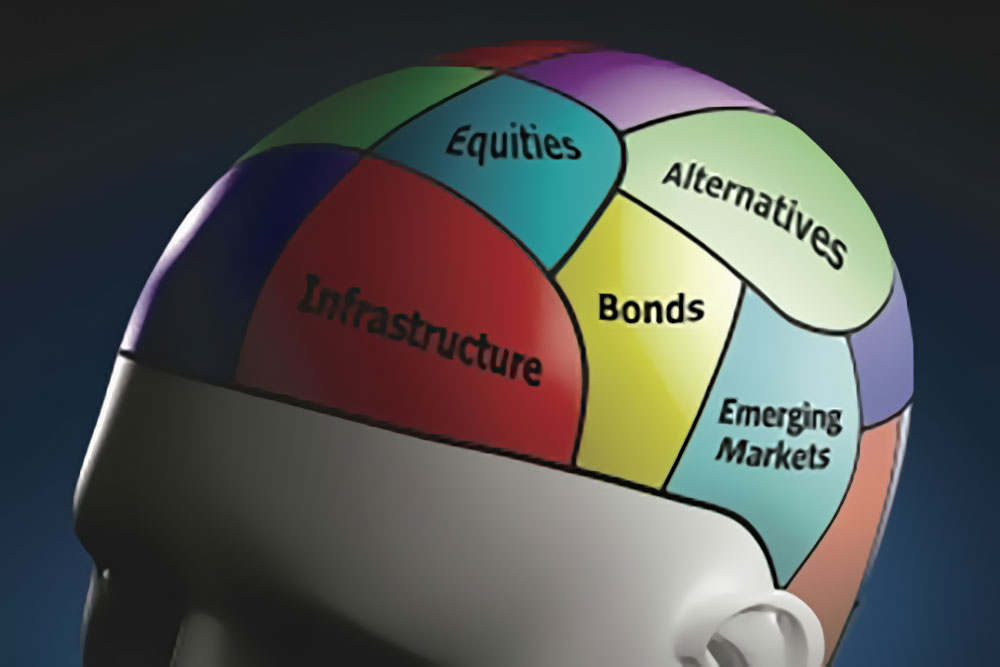

This letter is the start of a process we will, in the future, develop into a more useful and practical asset allocation framework for investors’ portfolios that reflects our macro view, concerns about the general riskiness of the financial world and a variety of issues that go into the asset allocation process.

As a starting point, it is important to understand what real long-run rates of return have been for different assets.2 Good data exists on developed country equity markets by sector and on real estate. For example, most people know that the real long-run return on U.S. equities is about 6.5%. Small-cap stocks outperform large companies by a wide margin, value stocks outperform growth stocks, also by a wide margin, and small value stocks easily outperform small growth stocks. However, small companies have much greater volatility and business risk.

It is also well known that the real return on bonds lags the real return on stocks, but risk is much less. In a portfolio, the inclusion of some bonds along with stocks lowers risk faster than it lowers returns up to a point.

Real estate is another major asset that is widely held. Real returns have been significantly lower than stocks: roughly ½% on residential property and about 5% on income-producing commercial property. And the swings can be wild when easy access to mortgage credit fuels leveraged speculation. Consequently, perceptions of risk in real estate have shifted dramatically over the last few years.

Emerging markets and gold can also be very attractive additions to portfolios. However, the history of emerging markets is short and these markets are evolving quickly. Gold has been free to fluctuate in the market only since 1971 and there have been just two major bull markets.

The asset allocation process is highly complex. Different investors have very different time horizons and risk aversions. The experience of the past three years has shown that historical correlations can be extraordinarily misleading. Various asset classes unexpectedly became highly correlated and much more volatile than the historical pattern. Understanding future correlations is the critical issue. In the midst of a crisis, liquidity can evaporate as trading volumes dry up, hedge funds close to redemptions and private equity may accelerate capital calls and halt distributions with unfortunate timing. Hidden leverage comes to the fore, exacerbating illiquidity.

Our approach to asset allocation is focused on wealth preservation by controlling the overall exposure to risk assets in relation to macro conditions, valuation and market psychology. We are not attempting to forecast the specific performance of various asset classes as a means of facilitating market timing decisions, as history has shown that this is rarely a winning strategy. Rather, we will attempt to provide analysis that will help investors play a more active form of defence and offense with their portfolios.

In order to achieve these goals, we favour a dynamic approach to asset allocation, reviewing the portfolio and making adjustments on a quarterly basis or as conditions evolve, rather than sticking with fixed allocations come “hell or high water”. Systemic risk in the global economy is far higher than in the previous post-World War II years, volatility promises to remain extraordinarily high and the financial system may be subject to major shocks. This is a major theme running through The Great Reflation. In such an environment, a buy and hold approach to asset allocation will carry a lot more embedded risk than most people expect.

In practice, the execution of dynamic asset allocation is subjective and highly complex for global investors. Many attempts have been made to create models or algorithms that rely on indicators to calculate an optimum asset allocation. However, this sort of quantitative approach inevitably breaks down as the assumptions that underpin the model cannot fit every set of economic conditions. We use indicators selectively to inform decision-making, but at its core, asset allocation is an art, involving equal measures of analysis, intuition and common sense. Above all, investors must have a clear idea of their tolerance for risk, exercise discipline and stick to a plan. Some prefer one of rigid allocations and the literature tends to support this approach. We favour a dynamic allocation process which allows for some flexibility in order to better control risk at important market junctures (e.g. stocks in 1999, housing in 2006-2007).

Comments are closed.