I bought corporate bonds and all I got was this stupid currency exposure

by Corey Hoffstein, Think Newfound Research

Summary

- In the current “Fed on / Fed off” market environment, dollar exposure matters

- Currency hedged exposures have exploded in popularity in the equity space

- Using the experience of Canadian investors, we demonstrate the large impact that currency can have on fixed income

- Investors buying global bonds should consider whether currency hedging makes sense for them

Currency hedging remains a topic of debate in ETF markets as dollar-hedged equity ETFs continue to grow.

The quick story behind these products is that for U.S. investors, returns in foreign markets can be largely wiped away if the dollar strengthens over the same period the investor is invested. This occurs because foreign investment requires us to convert our currency exposure. When we buy German stocks, we must first turn our dollars into euros. When we sell, we must subsequently turn our euro proceeds back into dollars. If, over the same period, the dollar rallies against the euro, we will see our profit eroded or our losses exacerbated.

This was the case for U.S. investors in 2014, when European stocks were up nearly 20% in euros but the dollar rallied so hard against the dollar as to leave them with almost no return.

The solution? Hedge the dollar exposure!

We’ve talked about this in the past. Our favorite paper on the subject is by Catherine LeGraw at GMO (you can read it here). The takeaway is simple: currency hedging isn’t black-or-white. But you probably don’t want to do it unless you have a currency view.

To date, the financial media has largely focused on the US investor’s perspective. But this affects international investors as well.

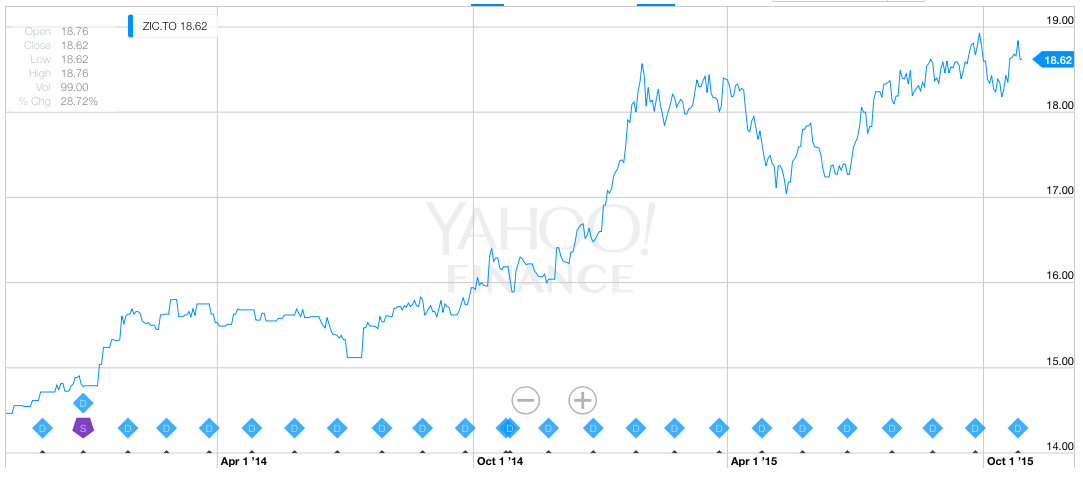

Newfound Research powers an index, published by NASDAQ, that is tracked by a First Trust ETF in Canada (TSX: ETP). The product is a dynamic ETF-of-ETFs portfolio , seeking a strong risk-adjusted yield (similar to our Multi-Asset Income strategy). One of the asset classes the ETF can invest in is mid-term US investment grade corporate bonds (TSX: ZIC).

, seeking a strong risk-adjusted yield (similar to our Multi-Asset Income strategy). One of the asset classes the ETF can invest in is mid-term US investment grade corporate bonds (TSX: ZIC).

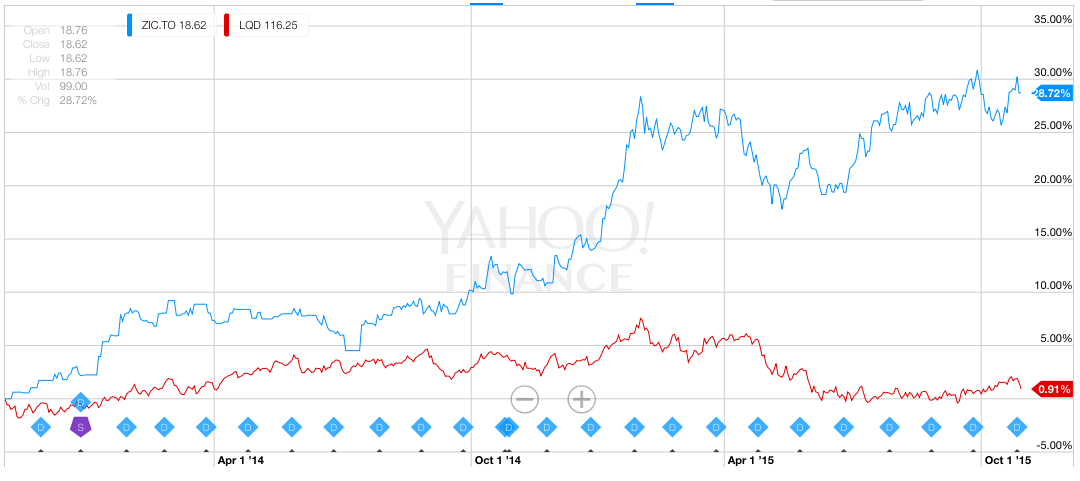

For investors that track corporate bonds, however, this looks absolutely nothing like what U.S. corporate bonds have done over the same period.

So what gives?

Simple: it’s the currency exposure.

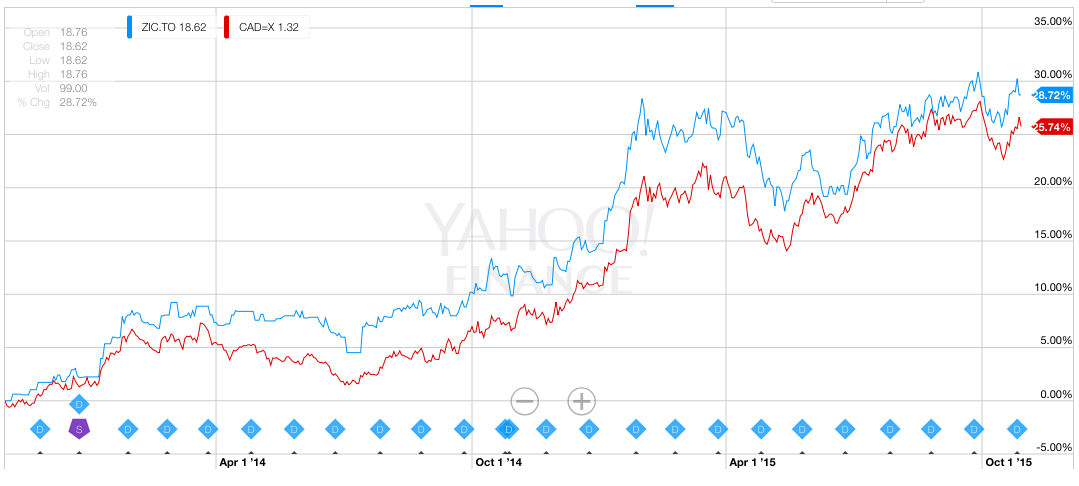

In fact, if we plot ZIC versus USDCAD returns, we see a high correlation.

The takeaway here is that the tremendous return Canadian investors have experienced from the ZIC ETF is driven almost entirely by the appreciation of the U.S. dollar against the Canadian dollar.

This brings up an interesting side of the debate not often seen in financial media: if we’re going to hedge currencies for equities, should we do it for bonds?

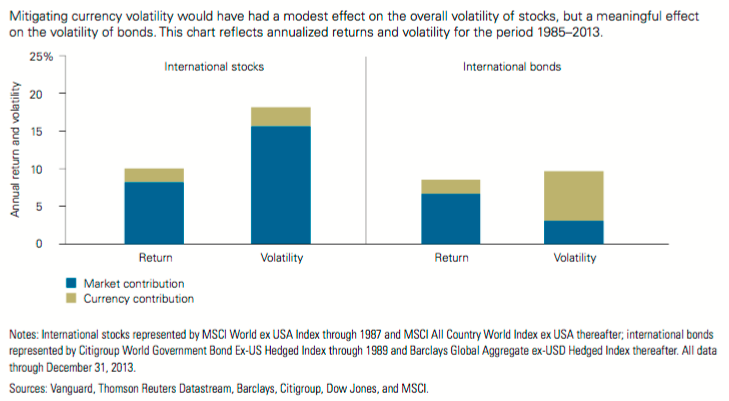

While we’re more on the fence for equities, we have a stronger view on bonds. Why? Quite simply because the volatility from currencies can completely overwhelm the volatility of the bonds we want to buy. Consider that if you’re buying mid-term corporate bonds today, you’re receiving something near a 3.5% yield. So without changes in credit spreads or interest rates, that’s about the return we can expect.

That return is easily dwarfed by the ability for a currency to move 20% in a year.

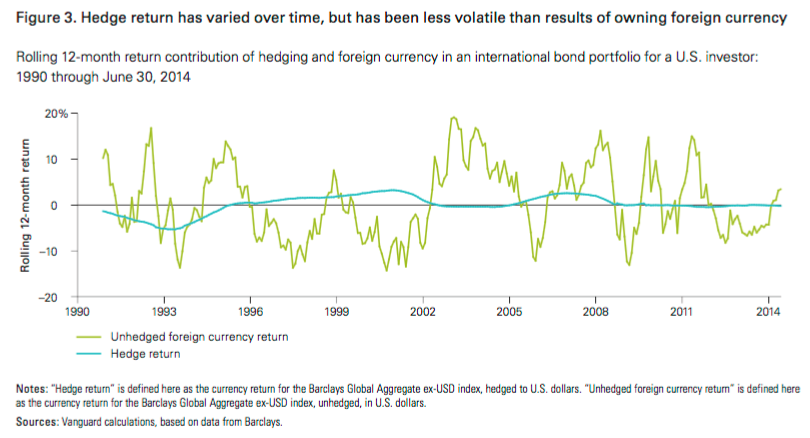

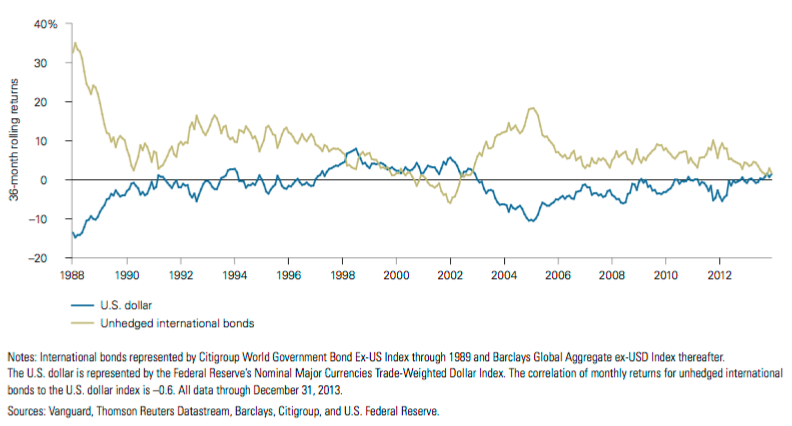

It should be no surprise, then, that a portfolio of currency-hedged bonds is much less volatile than a portfolio of unhedged bonds. Vanguard wrote a piece on this very topic from the U.S. investors’ perspective and the results are dramatic.

In fact, from another piece, Vanguard shows that unhedged international bond exposure, for a U.S. investor, is highly negatively correlated with the U.S. dollar.

This tells us one thing: the movement of the dollar is almost entirely controlling our return.

So it should be no surprise that once hedged out, the volatility of the international bond portfolio drops precipitously.

While Canadian investors have benefited from their exposure to the U.S. dollar, it is worth noting that the currency exposure can cut both ways. Had the U.S. dollar sunk against the Canadian dollar, they’d be deeply underwater with their corporate bond exposure.

All this being said, currency hedging isn’t free. Take the Canadian investor as an example. She wants to buy U.S. corporate bonds. If left unhedged, this purchase makes the investor long the U.S. dollar vs. the Canadian dollar. To hedge this, the investor – either directly or indirectly through a hedged investment vehicle – must enter a futures trade that is short the U.S. dollar / long the Canadian dollar.

Structurally, the futures position is like borrowing U.S. dollars today to purchase Canadian dollars. As a result, the hedge will add to (detract from) returns when Canadian interest rates are higher (lower) than U.S. interest rates. Fortunately for the investor, short-term interest rates are currency rates are currently higher in Canada than they are in the U.S. – so the hedge actually increases expected return (assuming that you have no view on currency fluctuations going forward). However, this is not always the case and is particularly important in hedging fixed income in a low yield environment because expected returns are low to begin with.

This has lessons for U.S. investors evaluating international bond exposures: unless hedged, don’t ignore the risk or return implications of currency fluctuations.

Copyright © Think Newfound Research