by William Smead, Smead Capital Management

Art has a tendency to express culture. One of today’s catchiest songs does a great job of explaining the relationship between institutional/individual investors and US common stock picking. In Gotye’s, “Somebody I Used to Know”, the lyric writer expresses the pain of a love affair gone awry and the feelings coming out of the former couple in words. To us at Smead Capital Management (SCM), the song captures what has happened since the summer of 1999, when Warren Buffett warned investors about forward stock market returns because of a love affair that institutional and individual investors were having with US large cap stocks. It takes us into today as Bill Gross from Pimco, David Rosenberg from Gluskin, Scheff and others encourage investors to underestimate the benefit of US large cap common stock ownership. At the same time, these purveyors of rational despair are driving investors away from stock picking when it is most likely to be advantageous to both institutions and individuals.

Now and then I think of when we were together

Like when you said you felt so happy you could die

Told myself that you were right for me

But felt so lonely in your company

But that was love and it’s an ache I still remember

Let me take you back to 1999, when investors and US large cap stock picking “were together” and investors loved their stocks until they “ached”. Buffett explained at the Allen and Co. gathering in Sun Valley, Idaho that the Fortune 500 index of common stocks was trading at 30 times earnings and was dooming US large caps to 17 years of sub-par performance. Stocks had performed spectacularly from August of 1982 to that summer day in Sun Valley. After 17 years of only occasional and mostly mild market corrections and years of prosperity, common stock investors in US large cap were “so happy they could die”. Their love for stock picking and stock pickers covered the pages of major media.

As Buffett shared, investors told themselves that common stocks “were right for them”. He quoted a UBS/Gallup poll which showed that the clients of UBS/Paine Webber expected 20% compounded returns over the next five years in US large cap common stocks. Picking common stocks and holding them for a long time was the national pastime. As I remember at that time, the over-pricing of US large cap growth/tech stocks made both Buffett and me feel “so lonely in your company”. No Bill Gross or David Rosenberg or any of today’s well known negative nabobs around to tell us where we’d be now beside the Oracle of Omaha.

Now and then I think of all the times you screwed me over

But had me believing it was always something that I’d done

But I don’t wanna live that way

Reading into every word you say

You said that you could let it go

And I wouldn’t catch you hung up on somebody that you used to know

People massively over did their affection for common stocks in 1999 and laid the groundwork for 12 years of extremely poor historical returns. Today both institutional and individual investors can only “think of all the times that you (US large cap stocks and stock pickers) screwed me over”. The times were the 2000-2002 and 2007-2009 bear markets. Two 40%-plus bear market declines in an eight-year stretch. It caused investors “believing it was always something” they had done. Ultimately, they decided “they didn’t want to live that way, reading into every word (Stocks for the Long Run) you say”. Investors decided common stocks “could be let go” and the stock pickers and US large cap companies were “somebody they used to know”.

But you didn’t have to cut me off

Make out like it never happened and that we were nothing

And I don’t even need your love

But you treat me like a stranger and that feels so rough

No you didn’t have to stoop so low

Have your friends collect your records and then change your number

I guess that I don’t need that though

Now you’re just somebody that I used to know

Unfortunately, the rear-view mirror never creates a good vision of the future. Investors for the most part have dramatically “cut off” their allocation of US large cap equity ownership. Worst of all, they “make like” the good years in the history of the stock market “never happened”. Investors have gone to the ends of the earth and to esoteric and illiquid investments to seek investment affection and act like they “don’t even need your love”. Here is how the logic goes. Investors say, “Stocks have performed poorly the last 12 years and haven’t met our return goals. Therefore, we will assume they never will. It will make me feel better if I assume that successful common stock investing was a statistical aberration and a thing of the past.” Isn’t it terrific that numerous self-interested gurus come by to regularly reinforce this rear-view mirror logic (The Cult of Equity is Dead).

You can get addicted to a certain kind of sadness

Like resignation to the end, always the end

So when we found that we could not make sense

Well you said that we would still be friends

But I’ll admit that I was glad it was over

On May 31, 2012, Randall Forsyth wrote at barrons.com that all of this has morphed into what he calls “rational despair”. Like the song says, “You can get addicted to a certain kind of sadness.” You look around you and see unsolvable economic problems, poor backward-looking stock market returns, dysfunctional governments around the world and you despair in a very logical way. You resign the US economy and stock market to a bad end and you hoard cash or invest in doomsday categories to justify your hopeless attitude. Gotye wrote, “Like resignation to the end, always the end”. If I had five dollars for every doomsday email I’ve been sent in the last three years, I’d be flush with cash. People look at US large cap stocks and stock pickers and “found that we could not make sense”. Some folks have gravitated to large cap indexes and ETFs because they said, “that we would still be friends”. Despite strong returns since the market lows of March 2009, those who despair rationally “admit that they are glad it was over”. It was their love for stocks and stock pickers that was gone.

But you didn’t have to cut me off

Make out like it never happened and that we were nothing

And I don’t even need your love

But you treat me like a stranger and that feels so rough

No you didn’t have to stoop so low

Have your friends collect your records and then change your number

I guess that I don’t need that though

Now you’re just somebody that I used to know

Cutting yourself or your institution off from owning healthy quantities of US large cap stocks based on the logic we’ve explained is like cutting off your nose to spite your face. Women in Northern Europe cut off their nose to look ugly to avoid being raped by conquering armies. In the same way, those who “make out like it (US stocks historically above-average returns among liquid asset classes) never happened” are, in our opinion, dooming themselves to sub-par portfolio performance at a time when above-average returns have never been needed more! Investors treat long duration common stock investing in US large cap stocks “like a stranger and (for stock pickers) that feels so rough”. “You didn’t have to stoop so low” when it comes to your portfolio allocation to US large cap and to active managers in the category.

Today, US large cap stocks are in a more similar position to 1982, than to anything like 1999. In 1982, we had high unemployment, huge budget deficits and loans for home buying or business formation were hard to come by. Stocks had performed poorly for over a decade. Gold, Oil and collectibles were popular among those who saw that era as made up of unsolvable problems and despaired rationally. Fortunately for us, the same guy who warned us in 1999 has laid out the right long-term view for us today. Here is how Warren Buffett puts the current circumstance in excerpts from his annual letter to the shareholders of Berkshire Hathaway called, “The Basic Choices for Investors and the One We Strongly Prefer”:

Investing is often described as the process of laying out money now in the expectation of receiving more money in the future. At Berkshire we take a more demanding approach, defining investing as the transfer to others of purchasing power now with the reasoned expectation of receiving more purchasing power – after taxes have been paid on nominal gains – in the future. More succinctly, investing is forgoing consumption now in order to have the ability to consume more at a later date.

From our definition there flows an important corollary: The riskiness of an investment is not measured by beta (a Wall Street term encompassing volatility and often used in measuring risk) but rather by the probability – the reasoned probability – of that investment causing its owner a loss of purchasing-power over his contemplated holding period. Assets can fluctuate greatly in price and not be risky as long as they are reasonably certain to deliver increased purchasing power over their holding period. And as we will see, a non-fluctuating asset can be laden with risk.

Investment possibilities are both many and varied. There are three major categories, however, and it’s important to understand the characteristics of each. So let’s survey the field.

- Investments that are denominated in a given currency include money-market funds, bonds, mortgages, bank deposits, and other instruments. Most of these currency-based investments are thought of as “safe.” In truth they are among the most dangerous of assets. Their beta may be zero, but their risk is huge.

Over the past century these instruments have destroyed the purchasing power of investors in many countries, even as the holders continued to receive timely payments of interest and principal. This ugly result, moreover, will forever recur. Governments determine the ultimate value of money, and systemic forces will sometimes cause them to gravitate to policies that produce inflation. From time to time such policies spin out of control. Even in the U.S., where the wish for a stable currency is strong, the dollar has fallen a staggering 86% in value since 1965, when I took over management of Berkshire. It takes no less than $7 today to buy what $1 did at that time. Consequently, a tax-free institution would have needed 4.3% interest annually from bond investments over that period to simply maintain its purchasing power. Its managers would have been kidding themselves if they thought of any portion of that interest as “income.”

Under today’s conditions, therefore, I do not like currency-based investments

- The second major category of investments involves assets that will never produce anything, but that are purchased in the buyer’s hope that someone else – who also knows that the assets will be forever unproductive – will pay more for them in the future. Tulips, of all things, briefly became a favorite of such buyers in the 17th century.

This type of investment requires an expanding pool of buyers, who, in turn, are enticed because they believe the buying pool will expand still further. Owners are not inspired by what the asset itself can produce – it will remain lifeless forever – but rather by the belief that others will desire it even more avidly in the future.

The major asset in this category is gold, currently a huge favorite of investors who fear almost all other assets, especially paper money (of whose value, as noted, they are right to be fearful). Gold, however, has two significant shortcomings, being neither of much use nor procreative.

As “bandwagon” investors join any party, they create their own truth – for a while.

Over the past 15 years, both Internet stocks and houses have demonstrated the extraordinary excesses that can be created by combining an initially sensible thesis with well-publicized rising prices. In these bubbles, an army of originally skeptical investors succumbed to the “proof” delivered by the market, and the pool of buyers – for a time – expanded sufficiently to keep the bandwagon rolling. But bubbles blown large enough inevitably pop. And then the old proverb is confirmed once again: “What the wise man does in the beginning, the fool does in the end.”

- Our first two categories enjoy maximum popularity at peaks of fear: Terror over economic collapse drives individuals to currency-based assets, most particularly U.S. obligations, and fear of currency collapse fosters movement to sterile assets such as gold. We heard “cash is king” in late 2008, just when cash should have been deployed rather than held. Similarly, we heard “cash is trash” in the early 1980s just when fixed-dollar investments were at their most attractive level in memory. On those occasions, investors who required a supportive crowd paid dearly for that comfort.

My own preference – and you knew this was coming – is our third category: investment in productive assets, whether businesses, farms, or real estate. Ideally, these assets should have the ability in inflationary times to deliver output that will retain its purchasing-power value while requiring a minimum of new capital investment. Farms, real estate, and many businesses such as Coca-Cola, IBM and our own See’s Candy meet that double-barreled test. Certain other companies – think of our regulated utilities, for example – fail it because inflation places heavy capital requirements on them. To earn more, their owners must invest more. Even so, these investments will remain superior to nonproductive or currency-based assets.

Our country’s businesses will continue to efficiently deliver goods and services wanted by our citizens. Metaphorically, these commercial “cows” will live for centuries and give ever greater quantities of “milk” to boot. Their value will be determined not by the medium of exchange but rather by their capacity to deliver milk. Proceeds from the sale of the milk will compound for the owners of the cows, just as they did during the 20th century when the Dow increased from 66 to 11,497 (and paid loads of dividends as well). Berkshire’s goal will be to increase its ownership of first-class businesses. Our first choice will be to own them in their entirety – but we will also be owners by way of holding sizable amounts of marketable stocks. I believe that over any extended period of time this category of investing will prove to be the runaway winner among the three we’ve examined. More important, it will be by far the safest.

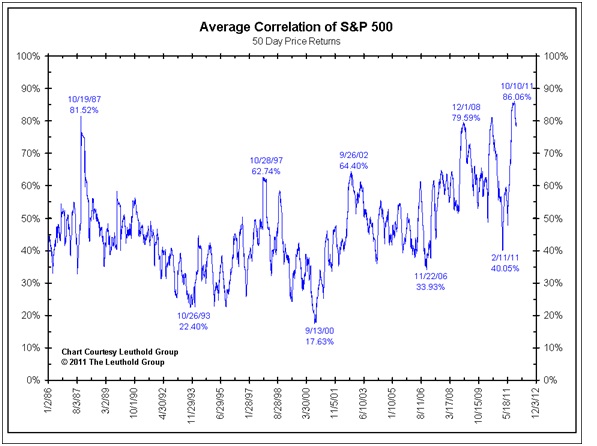

In our opinion, Buffett is the greatest stock picker of all-time and his portfolio is loaded with undervalued US large Cap stocks. Those who suffer from “rational despair” are massively over-weighted in the currency and unproductive assets that Buffett is warning everyone about. They are just like the bitter former lovers in the song who “wouldn’t catch you hung up on somebody that you used to know”. It is so ironic that investors today are having a love affair with the same asset-class allocation as they did in 1982 (Gold and Commodities). We believe the circumstances today scream for a new love affair to start between investors and US large cap stock pickers. Look at the long-term correlation chart below:

Source: The Big Picture, http://www.ritholtz.com/blog/2011/12/correlation-in-the-markets/

Our advice is to avoid stock pickers when stocks are expensive and correlations are low and milk them for years when correlations are high, like they are now. Correlations were the highest historically in 1982, 1987, 2002-03 and 2008-09. All these instances were around major US stock market low points. It might be time for asset allocators to “collect your records and then change your number” when it comes to US large cap and US large cap stock pickers. In that way you won’t have to look back ten years from now and view US large cap stocks and stock pickers as “just somebody that I used to know”.

Best Wishes,

William Smead

The information contained in this missive represents SCM’s opinions, and should not be construed as personalized or individualized investment advice. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. It should not be assumed that investing in any securities we recommend will or will not be profitable. A list of all recommendations made by Smead Capital Management within the past twelve month period is available upon request.

Copyright © Smead Capital Management