A Crisis Phobic Investment Culture?!?

by James Paulsen, Wells Capital

One of the legacies of the Great 2008 Crisis is it produced a widespread post-traumatic stress disorder we have referred to as “Armageddon hypochondria.” Simply, FEAR has dominated this recovery. Despite one of the strongest two-year advances in stock market history, throughout this period, investors have chronically and obsessively feared yet another overwhelming crisis. The current summer drama represents yet another panic surrounding a list of persistent and seemingly ever-increasing worries.

As would any hypochondriac, since the 2008 crisis the financial markets have often extrapolated a disappointing report (a symptom) instantly to “economic death” (i.e., a double-dip recession or depression). Since all recoveries ebb and flow, the contemporary economic patient has of course exhibited many troubling symptoms along the way—none yet, however, which have ended the recovery.

The current situation is no exception. Just like last year, the economy is in the midst of another soft patch. It could prove to be the start of a recession, or like last year, prove just a temporary but scary pause in an ongoing economic recovery. There have been some “recession-like” reports of late (e.g., the Philly Fed Business Outlook Survey and the recent reported collapse in consumer confidence) and the recent decline in the financial markets seem to suggest something horrible is coming. While a recession may indeed loom on the immediate horizon, we caution investors on the efficacy of signals provided by “survey reports” and by emotional financial market action against the backdrop of a culture which is suffering from Armageddon hypochondria.

Quantifying the Phobia?

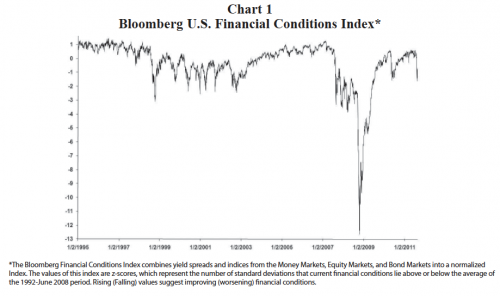

The following charts provide a quantification of the ongoing “crisis mentality” evident within the stock market during the last several years. Chart 1 is the crisis index. It gauges the degree of stress within the overall financial markets. Movements below zero represent periods of elevated financial market stress or a rising potential for a “crisis.” In a rough sense, this index portrays the financial markets’ assessment of the probability of a crisis (i.e., the likelihood of crisis rises as this index declines).

Chart 2 examines the rolling one-year regression coefficient between the daily percent changes in the U.S. stock market and the daily changes in the crisis index. Until 1997, the regression coefficient hovered around zero, suggesting movements in the crisis index had virtually no impact on the stock market. Crisis mentalities were not pronounced and the stock market seemingly was driven more by fundamentals (e.g., earnings and valuations). However, the back-to-back Asian and Russian crises of 1997 and 1998 significantly heightened investor crisis sensitivities. As illustrated in Chart 2, after the Asian/Russian debacles, the regression coefficient hovered about 5 percent implying that the stock market tended to fall (rise) by about 5 percent for every 1 point decline (increase) in the crisis index. Ever since, investor mentalities surrounding potential crisis risk have remained elevated! Indeed, the dot-com meltdown in 2000 led to an additional doubling in the stock market sensitivity coefficient to changes in the crisis index (i.e., the regression coefficient spiked to more than 10 percent at its peak in early-2003). Even though the regression coefficient did decline steadily during the last economic recovery (falling to only about 2 percent in 2007), it spiked again above 10 percent during the 2008 crisis and has only declined to about 8 percent so far in the current recovery.

Perhaps the watershed shift in the last decade toward an intense focus on “crisis” is best illustrated by Chart 3. It records the R-squared of one-year rolling regressions or the proportion of the total variability of the stock market which is “explained” by changes in the crisis index. That is, the proportion of market action explained by “crisis fears.” Prior to 1997, movements in the crisis index explained virtually none of the variability in stock prices. There was not a very strong crisis mentality. By contrast, during the last year, changes in the crisis index have explained almost 80 percent of the daily movements in the stock market!

The lost decade since the late 1990s has altered the focus from fundamentals to fear and has produced an investment class which is “crisis phobic”! What are the implications of such an investment culture?

Reflections on a Crisis Phobic Investment Culture?

1. More emotional market episodes?

What has produced the increased frequency of stock market swoons in recent years (e.g., the run on U.S. bank stocks in March 2009, the contemporary European bank stock run, a VIX reading above 80 in 2008 and twice in excess of 40 during this recovery, an unprecedented “flash crash” during the 2010 soft patch, and a record-setting number of days of 4 percent daily stock market moves a couple weeks ago during the current soft patch)? Is it because of high frequency trading, hedge fund actions, the increased popularity of quantitative trading approaches, the introduction of new “leveraged” trading instruments, insufficient margin requirements, issues surrounding the uptick shorting rule, or illiquid markets? Perhaps, but probably not. Rather, the increased tendency of the financial markets toward emotional tantrums more likely reflects the birth and maturation (over 10 years in the making) of a crisis phobic investment culture.

Throughout most of the post-war era, the U.S. stock market was driven primarily by underlying economic and company fundamentals and only infrequently would price action significantly diverge because of some overwhelming cultural panic. However, the crisis phobic culture evident today has produced a stock market seemingly driven mostly by “fears” which are occasionally suppressed by solid fundamentals. As long as the culture remains crisis-centric, the financial markets will likely be characterized by more frequent emotional and volatile market episodes. Investors, however, are probably best served by staying focused, not on the “rolling popularized crises,” but rather on the underlying fundamentals and relative valuations.

2. Are market signals and surveys reliable indicators in a crisis-phobic culture?

Financial markets (e.g., stock, bond, and commodity price movements and high yield, swap, or LIBOR yield spreads) have traditionally represented good leading indicators of economic fundamentals. However, we think investors need to question whether these historic relationships remain accurate and useful when the culture is so crisis-phobic? When financial market prices becomes so divorced from underlying fundamentals because of a widespread and intense panic, do they still offer the same forecasting content they typically do in calmer environments? For example, is the recent collapse in the 10-year bond yield to 2 percent suggesting a period of upcoming weak economic growth, a near-term deflationary surge, a Japan-style depression, simply an investor run to a safe haven asset, or does it just reflect the recent Fed announcement that interest rates will remain low until at least 2013? Who knows? And, if the 10-year yield is distorted or disconnected from underlying economic fundamentals, the efficacy of other yield spreads must also be questioned.

Finally, are “survey data” (e.g., consumer or business confidence reports) in such an emotionally charged, crisis-phobic, 24-7 media world providing the same economic signals they have in times past? Perhaps market signals and survey data remain accurate windows to the future but until the culture returns to one which is less crisis-phobic, we think investor caution in interpreting these signals is warranted.

3. Crisis-culture will diminish if recovery continues!

As illustrated in Chart 3, the U.S. has only had a single full economic recovery (i.e., the 2002 to 2007 recovery) since the investment culture first tended toward a crisis focus beginning in the late 1990s. As suggested by the rolling R-squared history, the crisis culture will likely decay as the economic recovery matures. During the Asian and Russian debacles in 1997 and 1998, the R-squared surged to about 60 percent, but a continued economic recovery eventually caused the sensitivity of the stock market to “crisis” (the R-squared) to decline back to only about a 20 percent R-squared by 2000. Similarly, at the start of the last recovery in 2002, the trailing one-year R-squared to the crisis index was about 70 percent, but by 2006 this had also declined to below 20 percent.

Despite the current widespread focus on U.S. government debt woes and on the European sovereign debt crisis, the contemporary crisis-phobia will likely fade in the next few years if the economic recovery continues. Our belief, as suggested by Charts 2 and 3 in the last recovery, is investors who can stay focused on the fundamentals and avoid having their investment strategy derailed by ongoing crisis concerns will fare the best.

4. Is crisis focus a good indicator of stock market risk?

As suggested by Chart 3, since crisis became a sustained focus in the late 1990s, the biggest risk for stock investors has usually been when the trailing R-squared was low—that is, when the cultural mindset was not as focused on the potential for a crisis. At the top of the 2000 stock market, the R-squared was only about 20 percent (i.e., in the previous year, few feared a crisis). Similarly, the 2007-2008 stock market collapse began when the R-squared was only about 30 percent.

By contrast, some of the best buying opportunities in the stock market since the late 1990s have occurred when the R-squared (or cultural focus on the potential for a crisis) was high. The 1998 stock market low during the Russian debacle occurred at an R-squared above 60 percent, the dot-com stock market collapse bottomed in late 2002 as the R-squared approached 70 percent, the 2009 stock market bottom was reached when the R-squared was around 50 percent, and the 2010 soft patch stock market bottomed as the R-squared surged toward 70 percent. Like a spike in the VIX volatility index, today, with the crisis index R-squared near 80 percent (suggesting an intense and widespread crisis focus), Chart 3 suggests it may be a good time to buy.

5. What is the near-term potential for stocks should the contemporary crisis fear ease?

As shown in Chart 1, the crisis index has declined by about 2 points since this mini-panic began earlier this summer. So what is the short-run potential for stocks should crisis fears fade (as they did after last year’s soft patch panic) and the crisis index returns to the level it was prior to this panic? Chart 2 shows the stock market currently exhibits about 8 percent sensitivity to every single point move in the crisis index. If the crisis index returned to its level earlier this summer, it would rise by about 2 points. Therefore, the stock market could rise by about 16 percent should this mini-crisis end. From its current level of about 1175, a 16 percent advance suggests the S&P 500 would return to its recovery cycle high near 1365 achieved earlier this year.

6. What is the long-term potential for stocks should crises fears ease?

Looking once again at Chart 3, what is the potential for the stock market should the R-squared to crisis diminish in the next several years as it did during the last recovery? Currently, almost 80 percent of the movements in the stock market during the last year are due to cultural crisis fears. This intense crisis focus leaves little room for investors to base stock valuations on fundamentals. Moreover, it probably explains why the S&P 500 currently sells at only about 12 times year-end estimated earnings per share while the 10-year Treasury yield is only about 2.2 percent, and while in the latest quarter, U.S. corporate profits rose at the robust annual rate of 12.8 percent!

If cultural mentalities were less crisis-phobic today, what would the PE multiple be on the stock market coming off a 12.8 percent profit quarter with a 2.2 percent Treasury yield and only about a 1.6 percent core consumer price inflation rate? Certainly, much higher than 12 times earnings! 16 times earnings? 17 times? This simply illustrates just how much the crisis-centric mindset is depressing investment potential and it also suggest how much opportunity there is to increase stock valuations just by improving the cultural mindset. Long term, the real investment opportunity is not a dramatic improvement in economic or profit growth (although either or both could occur), but rather is just a slow but steady decay in “crisis-fears” similar to what we experienced during the last recovery. What will the PE multiple on the stock market be if the Rsquared in Chart 3 declines again at some point to only about 20 percent? Summary

The crisis-phobic culture evident since the late 1990s will not likely disappear anytime soon. This means investors will just have to expect periodic intense panics characterized by extreme stock market volatility. However, those who can stay focused on the longer-term fundamentals and attractive valuations and not be spooked away from equities during emotional panics will likely be rewarded in the long-run. The current intensity of crisis fears will likely diminish in the next several years. As the culture slowly turns away from an imminent expectation of crisis and focuses again more on fundamentals, the valuations applied to the stock market should rise substantially as greed slowly replaces fear.

Copyright © Wells Capital