Munger’s Revenge Part III: “Inexplicable and Inexcusable”

by Jeff Matthews

(With excerpts from “Secrets in Plain Sight: Business and Investing Secrets of Warren Buffett” Available now at Amazon.com)

(With excerpts from “Secrets in Plain Sight: Business and Investing Secrets of Warren Buffett” Available now at Amazon.com)

Prelude: From $100 to $62 Billion in 56 Years

In May 1956, seven of Warren Buffett’s friends and family members invested in a partnership that would be managed by that self-assured, 25-year-old Omaha investor. They would pay him no fee or salary, but he would keep a quarter of the profits he earned for them, provided they made at least a nominal 6 percent annual return.

The seven friends and family members invested $105,000. Warren Buffett himself put in a nominal $100. That’s right: one hundred dollars.

Over the next 13 years, Warren Buffett grew Buffett Partnership Ltd. into a $100 million fund. Thanks mainly to his incentive fee, $25 million of the fund belonged to him.

In1969 Buffett disbanded Buffett Partnership Ltd. and focused on managing its largest investment: a troublesome textile company called Berkshire Hathaway. By 2002, that company was worth nearly $200 billion, and Buffett’s one-third ownership had put him on the top of the Forbes 400 list of richest human beings in the world, with a net worth of $62 billion.

From $100 to $62 billion, Warren Buffett’s investment legacy was secure around the world.

Mixed Messages

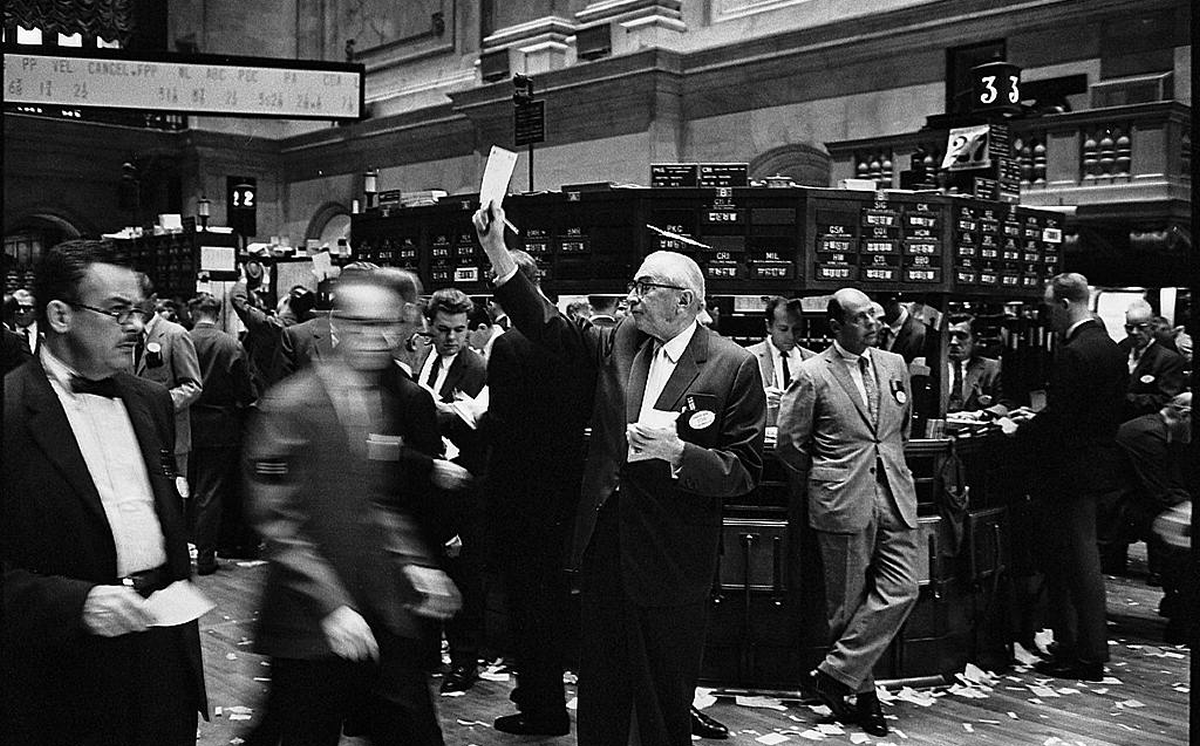

On Wall Street, however, it has been a bit more mixed. Buffett’s influence among investment professionals ranges from “value” investors who have studied him for decades and run their own funds very much in line with Buffett’s methods, to money managers who think the technology-phobic Buffett is brilliant but old-fashioned and out of step with the times.

There are even some downright cynics who regard Warren Buffett’s eye-popping career as a statistical fluke, consider Berkshire Hathaway to be something of a cult, and view Buffett himself as a kind of Teflon-coated master of public relations.

Call the cynics jealous, if you like—there is, in fact, no person alive who can match Buffett’s professional track record, and none who likely ever will. But there are some interesting contradictions between what Buffett says publicly and what he does as CEO of Berkshire Hathaway.

Do as I Say, Not as I Do?

During the hostile takeover boom of the 1980s, for example, such companies as International Paper and Salomon Brothers sold a special class of stock to Berkshire, solely to protect themselves from unfriendly takeovers. Warren Buffett, the implacable foe of clubby corporate boardroom behavior, was helping underperforming managers keep their companies intact and their jobs safe.

And after the collapse of junk-bond king Drexel Burnham Lambert in the early 1990s, Berkshire purchased billions of dollars worth of junk bonds despite Buffett’s own warnings that junk bonds were dangerous.

“The only time to buy these is on a day with no ‘y’ in it,” he liked to say.

More recently, just before the crisis hit in 2008, Berkshire announced it had taken in nearly $8 billion of premiums on 94 derivative contracts, similar to those “financial weapons of mass destruction” Buffett had been warning about for years. The derivatives included puts on various stock market indices with a nominal exposure of more than $40 billion.

Of course, these activities proved to be quite profitable (very profitable, in the case of the RJR bonds) for Berkshire’s shareholders. Just because Buffett casts a dim view on a particular investment class doesn’t mean he shouldn’t take advantage of a profitable opportunity when it appears within his “circle of competence.”

The Lucky Sperm Club...at Berkshire

More grating, and harder to rationalize, might be the sharper moral edge Buffett’s always blunt voice has taken on recently—especially considering his own history.

Buffett criticizes hedge fund managers because they charge big incentive fees and receive favorable tax treatment compared to common folk. Yet, Buffett Partnership Ltd was structured like a hedge fund, providing

Buffett with very large incentive fees and very favorable tax treatment.

Buffett also criticizes efforts to reduce the inheritance tax on rich families—“the lucky sperm club,” he sniffs. Yet Buffett has, quite deliberately, made Berkshire a haven for family companies that want to keep their business and their own management intact, while avoiding the very estate taxes he wants others to pay. In fact, Buffett has advertised the tax advantage of selling to Berkshire in his own Chairman’s Letter:

In making acquisitions, we have a further advantage: As payment, we can offer sellers [Berkshire] stock. …. An individual or a family wishing to dispose of a single fine business, but also wishing to defer personal taxes indefinitely is apt to find Berkshire stock a particularly comfortable holding.

Finally, Warren Buffett himself is dodging what must surely be the biggest estate tax bill of them all by giving away all his Berkshire stock instead of selling it.

Race against Time

These contradictions rankle in the quieter corners of Wall Street, although certainly not on Main Street, where Buffett has, in recent years, become a very public figure known around the world.

His higher public profile, of course, has a rational impetus: Buffett is engaged in a race against time to create a brand name for Berkshire that not only will attract family-owned businesses to become part of the Berkshire “family” but also will survive his death. The more exposure Buffett gets on CNBC and elsewhere—superficial as it may be—the better it is for Berkshire in the post-Buffett era.

And yet, while Buffett’s passing is a certainty—he’s now in his eighties—the answer to the question of whether Berkshire Hathaway will thrive without him is not.

Indeed, Berkshire shareholders got a harsh reminder of that fact thanks to the ugly end of David Sokol’s tenure at one of Berkshire’s largest and most important businesses.

Buffett’s handling of the abrupt resignation of David Sokol—after it was disclosed that Sokol had traded shares of Lubrizol for personal gain while Buffett was in discussion to acquire the company—triggered shock waves among many of Buffett’s longtime admirers and scorn from his detractors.

In that fateful March 30 press release, Warren Buffett—the very same Warren Buffett who told Congress 20 years ago, “Lose money for the firm, and I will be understanding; lose a shred of reputation for the firm, and I will be ruthless”—seemed to turn his back on that simple credo by writing, “Neither Dave nor I feel his Lubrizol purchases were in any way unlawful.”