by Liz Ann Sonders, Chief Investment Strategist, Charles Schwab & Company Ltd.

LizAnn: Hi everybody, welcome to the September Market Snapshot. Well, it's human nature or perhaps investor nature to be myopic at times and focus on the short term, especially these days with hypersensitivity to all things inflation and the labor market given uncertainty regarding Federal Reserve policy. Every day it seems the probabilities around what the Fed will do at the next meeting or one after that are pored over by investors trying to gain an edge. The thinking is if only the Fed would ease its foot off the economic break, we might assume the inflation dragon had been slayed and we could return to something resembling the pre-pandemic era. So how likely is that? That's what I want to address.

Let's widen the lens and ponder the possible transition we might be in the midst of, to perhaps a different secular environment. The secular era that preceded the pandemic is often referred to as the Great Moderation, one during which disinflation reigned, economic volatility was subdued, except maybe for the financial crisis, and there was a steady tailwind associated with the epic decline in interest rates. Now, the Great Moderation doesn't have an official start point, but in general, it's seen as kicking in during the 1990s. And that era had a number of key characteristics in addition to low economic volatility and disinflation, longer economic cycles, less frequent recessions, a Fed quick to press the easy policy button all the way to zero, profits representing an outsized share of GDP, and a positive correlation between bond yields and stock prices.

The era that preceded the Great Moderation started in the mid-1960s. I've been calling it the Temperamental Era. It had a very different set of characteristics. They included heightened economic volatility, more frequent recessions, sharper expansions, though on the upside, greater inflation and greater geopolitical volatility. It was also an era when labor via wages represented a much larger share of GDP relative to profits, and when there was a consistent negative correlation between bond yields and stock prices.

So let's have a look at some of these relationships. Looking at GDP, the swings were larger and recessions via the gray bars on the chart were more frequent during the Temperamental Era, but there were also sharper moves on the upside during expansions.

[Real GDP shadings – red for Temperamental Era and green for Great Moderation Era is displayed]

Now, once the inflation dragon was finally slayed in the early 1980s… thank you, Paul Volcker, and following a mild and very brief recession in the early nineties, the U S economy became much less volatile, as you can see with only two recessions prior to the pandemic. But as you can also see, both the economic highs and lows were lower than during the Temperamental Era.

And moving on to inflation, during the Temperamental Era, inflation volatility was on a tear, punctuated by the extreme peaks you can see during the mid to late 70s. And those extremes admittedly exacerbated by the Fed's decision on both occasions to declare victory and ease policy prematurely with the benefit of hindsight. only to see the inflation genie get let out of the bottle again. That led to the insertion of Paul Volcker as Fed chair, who, as we now say, “pulled a Volcker” by aggressively raising interest rates to get the inflation genie back in the bottle. Now, that did directly hit the economy. We had the famous double dip recessions in the early 1980s, but it laid the groundwork for the great Moderation Era to come.

Now, disinflation during the great moderation was aided by a number of forces that were GELing, and I've been using the GEL, G-E-L acronym, as it refers to the abundant and cheap access the world really had to goods, energy, and labor, courtesy of globalization, the U.S. energy boom, China coming into the WTO in 2001. For the most part, though, these three ships have sailed. Now, we don't ascribe to the simple deglobalization as it's often put out there, but instead believe that what we're seeing is a combination of regionalization, supply chain rationalization, supply chain diversification. In large part due to the ravages of the pandemic, companies have shifted essentially from what had been just-in-time to just-in-case inventory mindset. If you add climate change, geopolitics, war into the mix, I think you have the brew for a more volatile inflation era. By the way, that is distinct from saying a perpetually high inflation backdrop, more volatility.

Now, another interesting relationship that shifted notably between the two eras was profits versus labor compensation from the mid-60s to about the tech bubble burst in 2000, 2001, labor compensation as a share of GDP was persistently well above the share of GDP associated with corporate profits.

That switch was initially flipped due to the severity of the bursting of the tech bubble and the commensurate hit to profits. Profits then took a hit again for obvious reasons during the financial crisis, but since then have been in a range, but in a range near record highs as a share of GDP. Conversely, even with the brief spike during the pandemic, labor share of GDP has been well below profits share. You can see most recently another convergence has begun. I don't know whether it's going to continue, but I think this is key to watch, to get a sense of whether we are transitioning into an era that might look more temperamental.

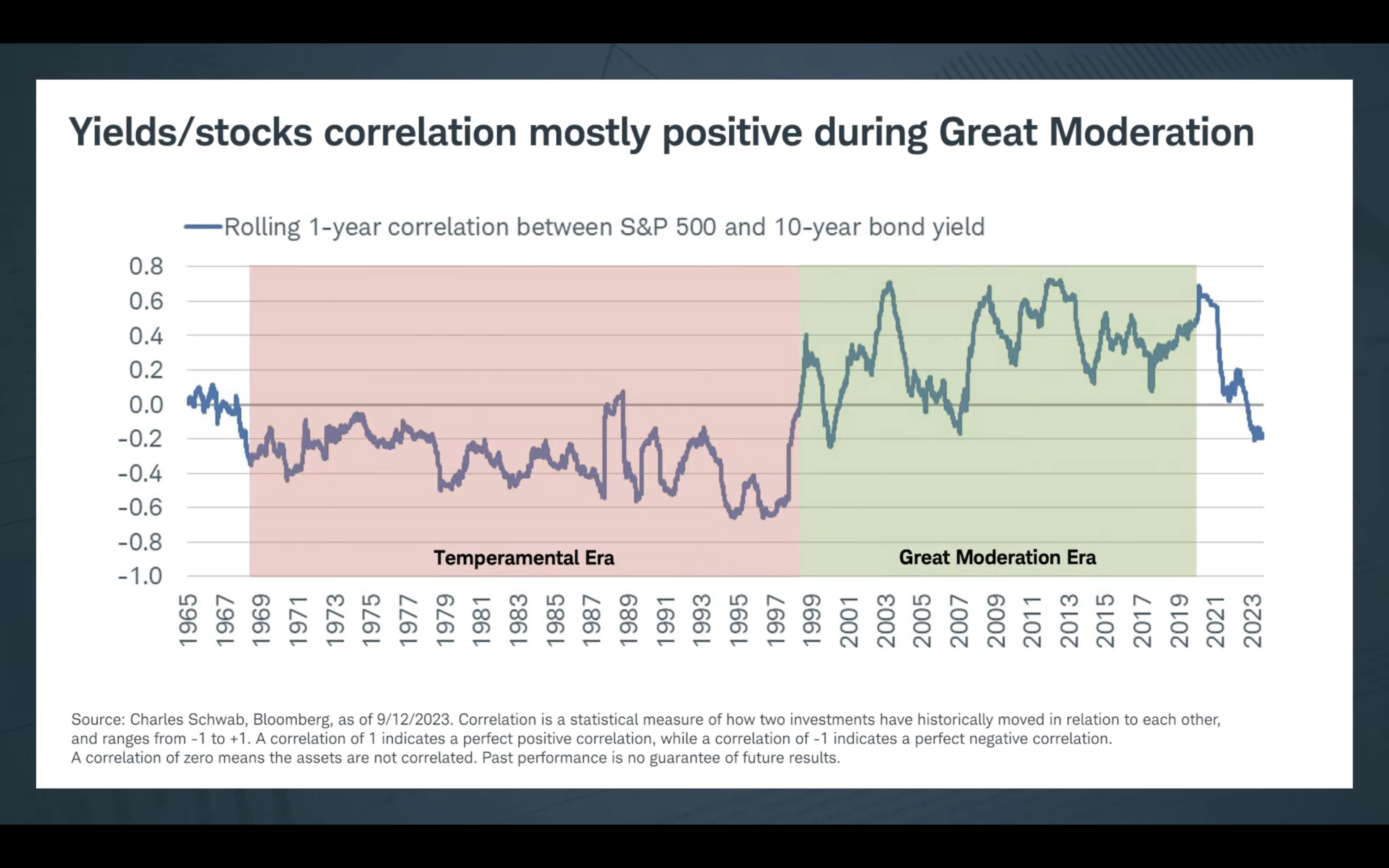

Now let's finish with a relationship that gets to the heart of possible investment implications if indeed we are transitioning. to a more temperamental era. And that's the correlation between moves in the 10-year treasury yield and moves in the S&P 500. During the 30-plus year period, starting in the mid 1960s, you can see the correlation was in negative territory for nearly the entire span. The explanation for this was, for the most part, inflation volatility. In other words, when yields were rising during this span, it was typically because inflation was rearing its ugly head. That's a tough environment for stocks, even if the growth is there. And the opposite was the case when yields were falling.

Now that was followed by a choppy transition around the bursting of the tech bubble. From that point until the pandemic, you can see the correlation was mostly positive other than a brief period during the height of the financial crisis. And the explanation for this was, for the most part, disinflation characterizing the landscape. In that environment, when yields were rising during this era, it was typically reflective of improving growth. without the attendant inflation problem. That's a great environment for stocks. And of course, the opposite was the case when yields were falling.

And if we're correct that the great Moderation Era is in the rear-view mirror, what are the implications, especially for this audience of investors? Now, many investors full history has been solely defined by the great moderation era, assuming a transition to a more temperamental era, even if it doesn't look exactly like what I'm defining as such, the investing landscape is likely to be changed. Not necessarily much worse or without opportunities, just different. We do believe we're likely to experience more volatility among inflation, yields, economic growth possibly, and geopolitics. And we also think that that will result in greater dispersion in equities returns and reinforces what has been our focus, as many know, for the past year or two, which is on factor-based investing, investing based on characteristics. Finally, the combination of higher economic and inflation volatility, the lessons learned from the zero interest rate policy experiments, surging government debt, a growing problem and its costs, likely mean policymakers, probably both monetary and fiscal, may have less flexibility in the future than they did during the great moderation. We are going to be speaking and writing on this subject a lot more in the near future, so stay tuned. But thank you as always for tuning in for this little bit of a preview.

Copyright © Charles Schwab & Company Ltd.