by Vaibhav Tandon, Senior Economist, Northern Trust

Policy responses to shortages are not always effective.

Rationing is the controlled distribution of scarce resources or a restriction of demand. It is an extreme measure typically undertaken in response to natural disasters, trade restrictions or wars, to mitigate the impact of scarcity.

Those living in the developing parts of the world are well familiar with the concept. For instance, the demand-supply gap in India regularly leads to power shortages or rationing of electricity. But at the moment, developed economies across Europe are facing the challenge of stretching scarce resources.

Russia has been increasingly weaponizing energy in its economic battle with the West. Natural gas flows through the important Nord Stream 1 pipeline to Germany have been suspended, escalating prices and raising the likelihood of rationing. European gas prices are now about ten times their average over the past decade. One-third of Europe’s energy comes from gas, which is used for generating electricity, transport and heating.

The rise in household energy bills and corporate sector energy costs are weighing on economic activity. Soaring energy bills are impairing household finances. Various industries, from fertilizer manufacturers to zinc smelters, are struggling to pay the cost of fuel. European energy trading is strained as companies find it difficult to guarantee trades amid wild price swings.

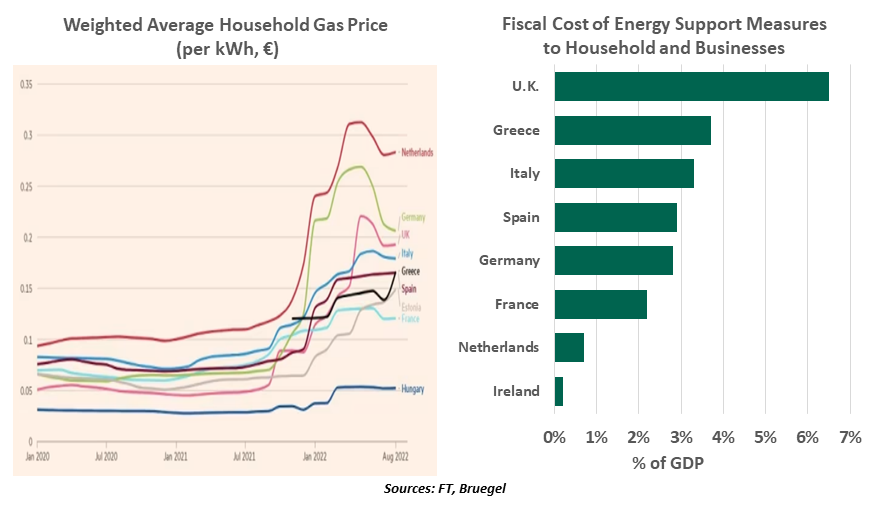

Governments are stepping in with measures to keep a lid on costs. According to Bruegel, European governments have allocated €450 billion to shield consumers and businesses from rising energy bills, an amount more than half of the post-pandemic NextGenerationEU program. Some EU nations have already launched windfall tax measures to subsidize household bills.

On average, European Union member states have allocated about 2.5% of gross domestic product (GDP) to offset the surge in energy prices. While most European countries have lowered taxes on petrol and diesel, they differ in their approaches and spending. Germany has provided a one-time €300 allowance for income tax paying workers. Italy has put in place a one-off €200 “cost of living bonus” for most salaried workers, self-employed workers and pensioners. In France, the government has put a freeze on gas prices for consumers, as well as a 4% cap on electricity price increases. The Norwegian government is paying 90% of households’ electricity bills when wholesale prices exceed prescribed thresholds.

Despite limited reliance on Russian energy, the U.K. is among the nations facing the biggest shock, with its households set to pay an average £2,500 a year on energy bills. To counteract this, new Prime Minister Liz Truss has proposed a £150 billion package of energy relief for households and firms.

There are pros and cons to offering relief for high energy prices.

Though the packages are crucial to keep the consumption engine running, they put central banks in an even tougher spot. By taking the edge off household utility bills, these measures could redirect spending to other non-essential areas of the economy, contributing to underlying price pressures.

European governments have been trying to wean themselves off Russian energy since the onset of the Ukraine war. The immediate focus has been on procuring liquified natural gas from other regions like North Africa, the U.S. and Qatar, but a lack of domestic transport infrastructure and terminals have impaired stockpiling.

EU states have reached a November 1 target to fill natural gas storage sites to 80% of projected needs for the winter, giving hope that severe rationing can be avoided. But not all member nations have gas storage facilities and will have to rely on neighboring states for supplies. Experience from the early days of the pandemic suggests that intra-European solidarity has limits. Major energy consumers like steel and chemical manufacturers are stepping up production cuts, which could create supply challenges. A harsh winter could force drastic demand-reduction measures. Rationing even in a handful of member states, especially in a country like Germany, will have ripple effects across the bloc due to close economic linkages.

Rationing provides governments with a way to constrain demand, regulate supply, and cap prices, but market interventions of this kind should be used sparingly. Europe needs to develop a long-term energy strategy that makes winter 2023, and all subsequent winters, a warmer experience.

Information is not intended to be and should not be construed as an offer, solicitation or recommendation with respect to any transaction and should not be treated as legal advice, investment advice or tax advice. Under no circumstances should you rely upon this information as a substitute for obtaining specific legal or tax advice from your own professional legal or tax advisors. Information is subject to change based on market or other conditions and is not intended to influence your investment decisions.

© 2022 Northern Trust Corporation. Head Office: 50 South La Salle Street, Chicago, Illinois 60603 U.S.A. Incorporated with limited liability in the U.S. Products and services provided by subsidiaries of Northern Trust Corporation may vary in different markets and are offered in accordance with local regulation. For legal and regulatory information about individual market offices, visit northerntrust.com/terms-and-conditions.

*****

Vaibhav Tandon

Vaibhav Tandon

Vice President, Economist

Vaibhav Tandon is an Economist within the Global Risk Management division of Northern Trust. In this role, Vaibhav briefs clients and colleagues on the economy and business conditions, supports internal stress testing and capital allocation processes, and publishes the bank's formal economic viewpoint. He publishes weekly economic commentaries and monthly global outlooks.