by Invesco Tax & Estate team, Invesco Canada

As adults, our legal, medical and financial affairs are generally left to our own discretion and acted on under our own authority. However, circumstances sometimes call for a substitute decision-maker in the event of absence or mental or physical incapacity. In contemplation of those situations, people often grant powers of attorney (POAs) to third parties to ensure important decisions can be made on their behalf, should the need arise. This article explains the basics of POAs and explores the issues surrounding beneficiary designations on registered plans when a POA arrangement exists.

There are two key parties to a POA:

- The grantor (sometimes referred to as the donor) is the individual on whose behalf decisions will be made

- The attorney is the individual who will make those decisions; in the context of a POA, the term “attorney” does not refer to a lawyer (although a lawyer can be appointed as attorney)

Different types of POA arrangements address different situations. With a general POA, the attorney’s powers exist only while the grantor has mental capacity. With an enduring/continuing POA, the attorney continues to have decision-making authority if the grantor becomes mentally incapacitated. Another arrangement, a springing POA, is valid once an event specified in the POA agreement occurs, generally when the grantor becomes incapacitated.

Although POAs confer significant powers on attorneys, those powers are not without limits. For example, the grantor may explicitly outline the areas of his or her affairs that fall within the attorney’s purview and outright exclude others. Beyond a grantor’s ability to specify limits to an attorney’s authority, provincial legislation governs the legal authority of attorneys, outlining hard parameters for establishing a POA and the scope of an attorney’s powers — and provincial laws differ with respect to what an attorney may or may not do.

General limitations on gifting and transfers

Although the rules vary from province to province, attorneys are generally limited in their ability to donate or gift the attorney’s property to other individuals. Depending on the province, there may be a limit on the monetary value of donations and gifts and restrictions on their purpose. Legislation in some provinces also prohibits gifts that would be uncharacteristic of the grantor. Even when a grantor authorizes a specific gift in the POA, an attorney may not be able to act on those instructions if they are outside the scope of an attorney’s powers, as defined in the relevant provincial legislation. As well, attorneys are generally unable to transfer the grantor’s property to themselves solely or jointly.

Beneficiary designations

A testamentary disposition is a gift or transfer of property that takes place on the death of an individual. Although the term is not defined in legislation, beneficiary designations made on registered plans, such as registered retirement savings plans (RRSPs), registered retirement income funds (RRIFs) and tax-free savings accounts (TFSAs), are generally considered testamentary dispositions. None of the Canadian provinces’ respective POA legislation allows attorneys to make testamentary dispositions on behalf of a grantor.

In a variety of scenarios, and specifically when the grantor no longer has mental capacity, this limitation could pose an issue. In some cases, the grantor may have been unaware that he or she never designated a beneficiary on registered plans. Even if the attorney has evidence to suggest the grantor would have wanted to name a specific individual as the beneficiary of those plans, the attorney cannot add that beneficiary. Due to mental incapacity, the grantor, too, cannot designate a beneficiary. In another instance, an attorney may discover that the grantor unintentionally left his or her ex-spouse as the beneficiary on an RRSP. Similarly, the attorney cannot rectify this issue by removing a named beneficiary from a registered plan.

More commonly, an issue can arise at the end of the year in which a grantor reaches age 71 and holds an RRSP, as tax rules cause RRSPs to mature at that time. Most RRSP administrators automatically convert the RRSP to a RRIF to avoid the fair market value inclusion of the RRSP proceeds as income to the annuitant if the RRSP funds were simply paid out of the plan. Unfortunately, beneficiary designations generally do not carry over to the new RRIF contract. Instead, the RRIF beneficiary typically defaults to the annuitant’s estate, unless the annuitant indicates otherwise. If the annuitant still has mental capacity, this is generally not a problem, as he or she can simply update the beneficiary designation on the new RRIF. However, if the annuitant is mentally incapacitated, the limitation on testamentary dispositions by an attorney generally prevents the attorney from stepping in to add the existing beneficiary designated on the former RRSP to the new RRIF.

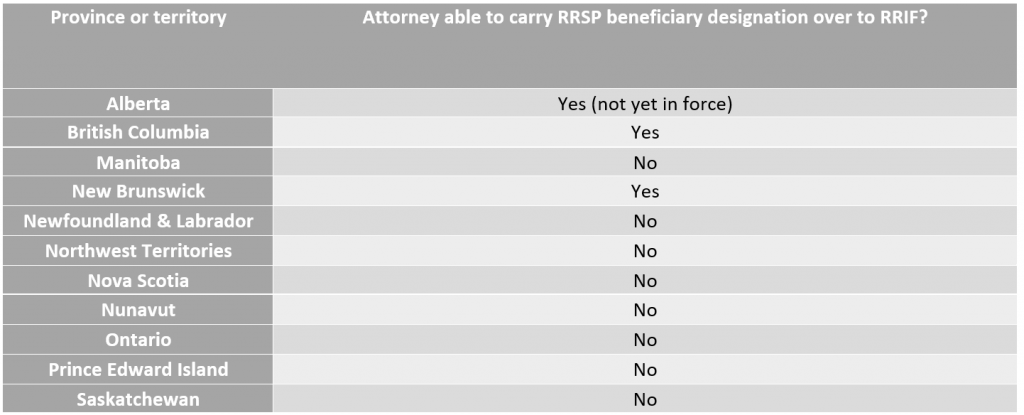

Some provinces have acknowledged the challenge this scenario poses to incapacity planning and addressed it to varying degrees. The following table outlines whether attorneys in each jurisdiction are permitted to carry the beneficiary designation over from a grantor’s RRSP to a grantor’s RRIF. Note that these rules apply to carrying over beneficiary designations to other similar plans, such as from a locked-in retirement account (LIRA) to a life income fund (LIF), or when transferring a plan from one financial institution to another. It may also be possible to carry over beneficiary designations across TFSAs belonging to the grantor, though this is less likely to be a concern, given that TFSAs do not mature.

At present, only British Columbia and New Brunswick have enacted legislation that enables attorneys to carry over beneficiary designations across plans. Alberta is slated to be the third province to introduce such measures, through proposals outlined in Bill 22, which passed its first reading in the provincial legislature in June 2020. Bear in mind that even in Alberta, British Columbia and New Brunswick, the attorney can only designate the beneficiary or beneficiaries named on the former plan immediately prior to the transfer to the RRIF. Although only a limited number of provinces currently allow (or, in the case of Alberta, will soon allow) this beneficiary carryover treatment, calls have been made for further review of the issue in other jurisdictions. In 2013, the Ontario Bar Association appealed to the Ministry of the Attorney General to amend existing legislation to enable this approach. In 2015, the Nova Scotia Law Reform Commission expressed similar sentiments.

With an aging population across the country, encounters with this matter will become more prevalent. It is encouraging that Alberta, with Bill 22, has shone new light on the subject. This lends hope to the possibility that further provinces and territories will follow suit with reforms to their legislation. In the meantime, the risk that comes with transfers into new accounts that do not carry over the old beneficiary designations cannot be eliminated entirely. However, practitioners in the areas of incapacity and estate planning may be able to mitigate those risks by keeping a keen eye on registered plans to ensure that the accountholder makes beneficiary designations, when possible, whenever a new registered plan is created.

This post was first published at the official blog of Invesco Canada.