by Veerapan (Veeru) Perianan, Senior Quantitative Analyst, Charles Schwab Investment Advisory, Inc.

Key Points

- Market returns on stocks and bonds over the next decade are expected to fall short of historical averages.

- The main factors behind the lower expectations for asset returns are low inflation, historically low interest rates, and equity valuations.

- International stocks appear more attractive than U.S. stocks based on valuations, underscoring the importance of investing in a diversified portfolio.

Market returns on stocks and bonds over the next decade are expected to fall short of historical averages, while global stocks are likely to outperform U.S. stocks, according to our Q1 2020 estimates.¹

This article provides a broad overview of the methodology used for calculating our capital market return estimates and highlights the importance of global diversification and maintaining long-term financial objectives that are based on reasonable expectations.

The main factors behind the lower expectations for market returns are below-average inflation (despite a recent rise in expected inflation), historically low interest rates, and elevated equity valuations.

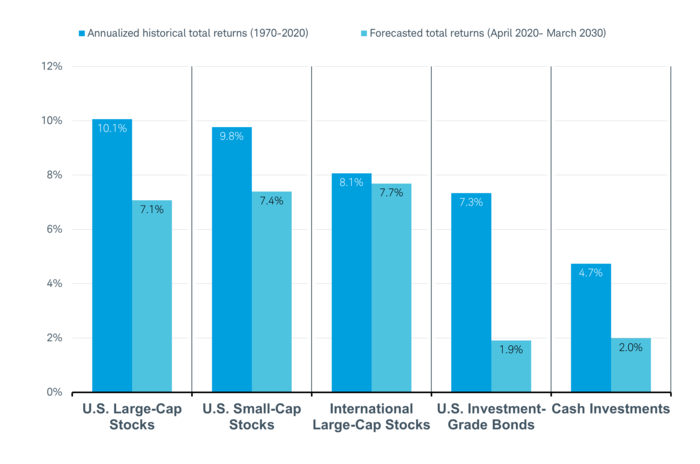

The reduced outlook follows an extended period of double-digit returns for some asset classes, as shown in the chart below. As such, now may be a good time for investors to review, and consider resetting, long-term financial goals to ensure that they are based on projections grounded in disciplined methodology rather than on historical averages.

Curb your expectations and consider going global

Total return = price growth plus dividend and interest income. The example does not reflect the effects of taxes or fees. Numbers rounded to the nearest one-tenth of a percentage point. Benchmark indexes for the asset classes: S&P 500® index (U.S. Large-Cap Stocks), Russell 2000® (U.S. Small-Cap Stocks), MSCI EAFE Index® (International Large-Cap Stocks), Bloomberg Barclays U.S. Aggregate Bond Index (U.S. Investment-Grade Bonds), and Citigroup 3-Month U.S. Treasury Bill Index (Cash Investments). Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

Source: Charles Schwab Investment Advisory, Inc. Historical data from Morningstar Direct. Data as of 3/31/2020.

Our estimates show that, over the next 10 years, stocks and bonds will likely fall short of their historical annualized returns from 1970 to March 2020. The estimated annual expected return for U.S. large-capitalization stocks from April 2020 to March 2030 is 7.1%, for example, compared with an annualized return of 10.1% during the historical period. Small-capitalization stocks, international large-capitalization stocks, core bonds, and cash investments also are projected to post lower returns through March 2030. However, the expected annual return for international large-capitalization stocks is 7.7% over the next 10 years, which is higher than the expectations for U.S. large-capitalization stocks.

Cash investments are expected to earn more than certain bonds. Monetary policy, combined with investors’ flight to safety, has caused bond term premiums—that is, the difference between the yields earned by locking up money over an extended period vs. rolling over a short-term instrument (like Treasury bills) for the same period—to turn extremely negative. This suggests that bond returns are likely to remain subdued. We believe the long-run equilibrium return from rolling over T-bills is unlikely to be lower than long-term inflation estimates, but the dynamics at play for longer-term bonds are far more complex.

Here are answers to frequently asked questions about these market estimates:

Why are long-term estimates of returns important?

A sound financial plan serves as a road map to help investors reach long-term financial goals. To get there, investors need reasonable expectations for long-term market returns.

Return expectations that are too optimistic, for example, could mislead investors to expect their investments to grow at an unrealistically high rate. This may cause them to save less, in the hope that their investments might grow large enough to fund their retirement or big expenses. But when actual returns do not match these expectations, it could lead to a delayed retirement or make it difficult to pay for a big expense, such as a college education. On the other hand, if return expectations are overly pessimistic, too much may be saved in the nest egg at the expense of everyday living.

How do you calculate your long-term forecasts?

The long-term estimates cover a 10-year time horizon. We take a forward-looking approach to forecasting returns, rather than basing our estimates on historical averages. Historical averages are less useful, as these only describe past performance. Forward-looking return estimates, however, incorporate expectations for the future, making them more useful for making investment decisions.

For U.S. and international large-cap stocks, we use analyst earnings estimates and macroeconomic forecast data to estimate two key cash-flow drivers of investment returns: recurring investment income (earnings) and capital gains generated by selling the investment at the end of the forecast horizon of 10 years. To arrive at a return estimate, we answer the question: What returns would investors make if they bought these assets at the current price level to obtain these forecasted future cash flows?

For U.S. small-capitalization stocks, we forecast the returns by analyzing and including the so-called “size risk premium.” This is the amount of money that investors in small-capitalization stocks expect to earn over and above the returns on U.S. large-capitalization stocks.

For the U.S. investment-grade bonds asset class, which includes Treasuries, investment-grade corporate bonds and securitized bonds, our forecast takes into account yield-to-maturity of a risk-free bond, roll-down return, and a credit risk premium.² We believe the future level of return an investor will receive is anchored to a large extent by the yield of a 10-year U.S. Treasury bond. Treasury bonds are generally considered to be default-risk-free. Aside from this, roll-down return is an additional source of return bond fund investors typically earn, as they almost always invest in a bond portfolio that is designed to maintain an average maturity. For example, a roll-down return occurs when a bond fund manager sells a bond whose maturity falls below the average maturity of the portfolio. This process typically results in a gain, because yields on bonds with longer maturities are usually higher than on shorter maturities, and because bond prices rise when yields fall. Credit risk premium is the return an investor earns for taking on the risk of default, as when investing in a relatively riskier bond, such as a corporate bond.

Cash investments are very short-term in nature, typically not exceeding three months at a given time, and are reinvested at the end of each period for as long of a horizon as desired. We assume this horizon to be 10 years, and estimate the returns from cash investments over this period. We also make the assumption that cash returns, over this horizon, are not likely to fall below our 10-year inflation rate forecast.

Why do you expect long-term returns to be lower than historical averages?

Three primary factors are behind the forecast for reduced returns: lower inflation, low interest rates, and equity valuations.

- Low inflation. Inflation averaged 3.9% annually from 1970 to March 2020. Our inflation forecast comes from consensus estimates of leading economists. This is expected to average 2% from April 2020 to March 2030. When the rate of inflation is low, bond yields also have been low. That is because bond investors generally do not require as much yield premium to compensate for the erosion in buying power that inflation can inflict on a portfolio. For stocks, low inflation historically has meant low nominal (before inflation) returns. Nominal returns are the actual returns earned by investors, before adjusting for inflation.

- Low interest rates. Lower inflation affects yields on everything from cash to 30-year Treasury bonds. As noted earlier, we expect cash to earn a higher return than certain bonds. Current and expected interest rates are much lower than what has transpired historically, especially compared to the high-interest-rate environment of the 1980s. The Fed has once again started following a zero-interest-rate policy in response to the economic fallout due to COVID-19. Low yields mean investors earn less from the fixed-income portion of their portfolios.

- Equity valuations. Consensus forecasts of earnings and economic growth over the long term remain lackluster, which prompts us to remain cautious and to forecast returns that will be lower than their historical averages. High stock prices today, without a proportionate increase in future earnings, means lower expected returns going forward. But stocks still tend to have higher expected returns than bonds, as they generally have higher risks.

What could lead to higher returns?

Returns could exceed our expectations if the U.S. economy grows more than economists anticipate. According to consensus forecasts, economists expect 2% annual gross domestic product (GDP) growth over the next 10 years. Higher-than-expected economic growth would likely lead to higher earnings growth, driving stock and bond returns higher. An example of the economy growing faster than expected occurred from 1990 to 1999. During that period, economists expected annual GDP growth of 2.4%, while the U.S. economy actually grew at a much higher rate of 3.2% annually on average. Corresponding returns from U.S. large-capitalization stocks were 18.2% on average and core bonds averaged 7.7% despite severe market turbulence in 1998.

Why do you expect international stocks to outperform U.S. stocks?

As shown in the chart above, U.S. large-capitalization stocks are expected to return 7.1% annually over the next 10 years, compared to 7.7% for international large-capitalization stocks. This is mainly due to the valuation differences between U.S. stocks compared to international stocks.

What can investors do now?

Thanks to the power of compound returns, what investors do (or don't do) today can have big implications on their ability to meet their long-term goals.

Here are a few things to consider doing. First, if you don't have a long-term financial plan, now is a good time to put one together. Second, try to minimize fees and taxes, particularly in a lower-return environment. And last but not least: Build a well-diversified portfolio.

1 Charles Schwab Investment Advisory, Inc., a separately registered investment advisor and an affiliate of Charles Schwab & Co. Inc., annually updates the capital market return estimates.

2Treasury notes generate what is considered a “risk-free” rate, or yield, because of the negligible chance of the U.S. government defaulting on its debt obligations. A corporate credit “risk premium” is the amount of money that investors expect to earn above and beyond the yield because of the chance of a default by the corporation that issued the bond.

Copyright © Charles Schwab Investment Advisory, Inc.