by Darren Williams, Director—Global Economic Research, AllianceBernstein

At long last, the UK has left the European Union (EU). But now tough and unpredictable negotiations lie ahead. In our view, the probability that they end in a negative short-term economic outcome is greater than 50%.

At 11 p.m. GMT on Friday, January 31, the UK formally left the European Union (EU). Thank goodness for that, many will say. Unfortunately, it isn’t quite that simple, as the UK and the EU still need to reach agreement on the shape of their future trading relationship.

Transition Phase Will Be Short

Now that the UK has left the EU, it has entered a transition phase during which it retains most of the rights and obligations of EU membership. This phase should last until December 2020, but may be extended for an additional two years if this has been agreed on by July 1. The only problem is that the UK government has passed a law to rule this out.

Many observers regard the enforced December 2020 deadline as a negotiating tactic on the part of the British government (since there is nothing to prevent it changing the law back again later). However, we are inclined to take Prime Minister Boris Johnson at face value on this. Extending the transition phase would be seen by Conservative voters as a huge betrayal, while the last thing Johnson can afford to do is start looking like his predecessor. This is exactly what will happen if he allows himself to be sucked into a never-ending negotiating vortex by the EU.

What Types of Deal Are Possible by Year-End?

Just about the only thing we can say with any certainty is that it will be close to impossible for the UK and the EU to reach agreement on a comprehensive trade deal covering goods and services by year-end. The best that can be hoped for is a limited agreement that would include a zero-tariff regime for goods, but with the UK leaving the EU’s customs union and with no provision for services.

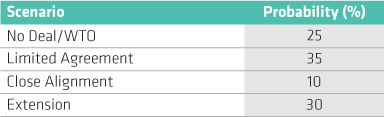

While it’s difficult to be too precise about the shape of the future trade agreement, we can identify four broad scenarios:

1) No Deal/WTO Terms—No agreement, with the trading relationship between the UK and the EU defaulting to World Trade Organization (WTO) terms. While the government now has more time to plan for this outcome, it would still be disruptive and would probably push the economy into recession in late 2020/2021.

2) Limited Agreement—A zero-tariff regime for goods but with no agreement on services and the UK leaving the EU’s customs union. This would previously have been called a hard Brexit. It would be less disruptive than no deal but could still impair growth.

3) Close Alignment—The UK and the EU somehow manage to agree on a comprehensive trade deal which keeps the UK in close regulatory alignment with the EU and minimizes economic disruption. Given the extent to which investment has been held back by Brexit-related uncertainty, this scenario would probably lead to a material rebound in growth.

4) Extension—Although the British government is reluctant to extend the time frame, it remains a viable scenario given the potential disruption that might otherwise occur (and ultimately, only Johnson knows if he’s bluffing). To some extent this is the status-quo scenario, though an extension is more likely to occur if negotiations are moving in a favorable direction.

What Will Brexit Look Like? Tentative Probabilities

It’s impossible to be too precise about probabilities for the four potential paths at this early stage. We’ll get more clarity once the UK and EU start talking to each other. But even then, we’d expect the situation to remain very fluid. With that in mind, tentative probabilities for each scenario are as follows:

The probability that the trade talks between the UK and EU end in a negative short-term outcome for the economy is therefore greater than 50%. And even if this is wrong, the negotiations are likely to be highly acrimonious and disruptive. The Bank of England Monetary Policy Committee was right not to cut interest rates at its January meeting, partly because there are signs that the most rate-sensitive sector of the economy (housing) is already picking up and partly because the economy may be in greater need of lower rates later in the year.

We’re forecasting two 25 basis point rate cuts for the UK in the second half of this year, and we expect the pound to return into a 1.20–1.25 range, perhaps lower in the most adverse scenario.

Darren Williams is Director—Global Economic Research at AllianceBernstein.

The views expressed herein do not constitute research, investment advice or trade recommendations and do not necessarily represent the views of all AB portfolio-management teams. AllianceBernstein Limited is authorized and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority in the United Kingdom.

This post was first published at the official blog of AllianceBernstein..