by Cole Smead, Smead Capital Management

A few weeks ago, Barron’s magazine mentioned a book that doesn’t get much play these days titled The Money Masters, authored by John Train. Train’s book was published in 1980 and contained biographies of nine great investors. Warren Buffett, Phil Fisher and Larry Tisch each had their own chapter. Names that have been forgotten in time are in there too. However, the chapters on Sir John Templeton and T. Rowe Price were the most interesting for the circumstances of today. Templeton’s career was built on practicing a value-oriented discipline in global markets that were under-owned for much of his career. Price was a growth stock investor that recognized in the late 1960’s that his style of investing was likely overcrowded. Both men sought to avoid popularity by the end of their careers and understood how the coming and going of seasons can change an investor’s view of a stock as prices go up or down.

Templeton had a global mandate for the Templeton Growth Fund that allowed him to invest in both U.S. and non-U.S. stocks. Train explained some of Templeton’s reasoning:

Incidentally, the willingness to invest in many countries ties in with a willingness to buy “junior” stocks. Quite often the smaller, cheaper, faster-growing company is outside the U.S.

Train’s description of this Templeton-framed view is a perfect picture of our investments in the media industry. Everyone wants to debate who will be the winner of the future of media. Will it be big-cap tech or will traditional media players win the war? The names thrown around in this discussion are Netflix, Amazon, Disney, Comcast, etc. We have what we believe to be incredibly profitable franchises in Discovery and Tegna that produce non-scripted shows.

These are Templeton-style “junior” stock holdings because they lack ownership by managers of size. The shareholder registry is littered with un-notable asset managers and ETFs. In effect, there is a lack of sponsorship of these companies. They do have some of the most successful media investors of all time in the shareholder rolls, in particular, Discovery’s John Malone. Follow the billionaires, not Wall Street. Secondly, these unscripted shows have lower production costs, especially relative to the people splashing money around Hollywood today on shows like Game of Thrones or The Crown. Producing cheap content that is profitable is better than selling expensive content and losing money. This requires us to not be found at the Emmy’s or the Academy Awards while people stroll down the red carpet while the red ink blends in.

T. Rowe Price’s name is synonymous with long-term ownership of outstanding growth businesses. Price referred to his investment approach as looking for “fertile fields of growth.” For Price, this meant “identifying an industry that is still enjoying its growth phase, and settling on the most promising company or companies within that industry.” Price’s firm became a notable owner of some of the great growth stories of the 1950’s and 1960’s like Black & Decker, 3M, Honeywell and Merck.

By 1971, Price had not only sold all his ownership of what we now know as the money management firm T. Rowe Price, but he also cut ties with the firm. Price’s goal for growth stock investing was “that a stock should double income and market value over 10 years.” As Train pointed out, this was “far from easy if it’s already forty or fifty times earnings.” He goes on to say, “What if something goes wrong?”

This consternation caused Price himself to move his personal capital to what he termed a “new era” approach: real estate, natural resources, gold and silver. Price was balking at the valuation of the kinds of companies he liked to own. His “new era” approach did great as the Nifty Fifty died in 1972 and growth died with it.

The very name “growth stock” became virtually taboo in Wall Street. The same institutions that had rapturously bought Avon in 1973 as a once decision holding at $130, or fifty-five times earnings then dumped it in 1974 at $25, or thirteen times earnings, until by late 1974 the wringing-out process had gone so far that Price himself decided it was safe to begin buying growth stocks once more, though not necessarily the same ones.

Price’s pivot away from this maniacal era of growth proved to reward his “new era” approach. Those assets appreciated greatly in the 1970’s in a tough era for growth stocks. Price was much like Templeton. He was a flexible investor that knew investment success was tied to the valuation of what he was buying.

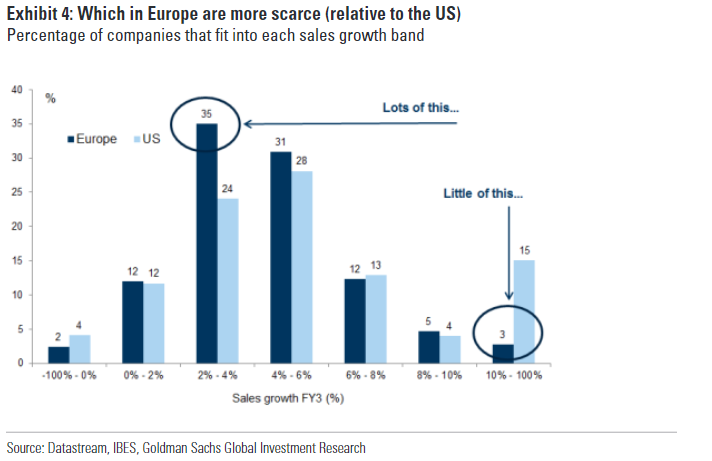

One way we think Price might look at the current era of stock investing is to compare the concentration of technology investments as a percentage of the overall U.S. and European markets. The chart below shows the percentage of companies divided by their respective sales growth rates.1 This era of growth stock excitement is all about revenue growth. As Europe has fewer of these high revenue growth businesses, it would naturally not catch the bid its American counterpart would.

For Templeton and Price to execute a “new era” approach today, we believe they would likely advocate avoiding the S&P 500 Index, mutual funds and ETFs, emphasizing growth stock investing and they would be very careful with ownership of anything related to technology. Price recognized that growth eras don’t continue forever and Templeton went wherever he thought he could make great money buying companies at depressed prices with positive economics. We believe our eight criteria for common stock ownership will shepherd us through this “new era.”

Warm regards,

Cole Smead, CFA

1Source: Goldman Sachs, “Why Technology is not a bubble” published June 4, 2018.

The information contained in this missive represents Smead Capital Management’s opinions, and should not be construed as personalized or individualized investment advice and are subject to change. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. Cole Smead, CFA, Managing Director and Portfolio Manager, wrote this article. It should not be assumed that investing in any securities mentioned above will or will not be profitable. Portfolio composition is subject to change at any time and references to specific securities, industries and sectors in this letter are not recommendations to purchase or sell any particular security. Current and future portfolio holdings are subject to risk. In preparing this document, SCM has relied upon and assumed, without independent verification, the accuracy and completeness of all information available from public sources. A list of all recommendations made by Smead Capital Management within the past twelve-month period is available upon request.

Copyright © 2018 Smead Capital Management, Inc. All rights reserved.