by Brian Phillips, Director—Commercial Real Estate Credit Research, AllianceBernstein

Headlines about the death of the American shopping mall have become so common that the phrase “retail apocalypse” has its own Wikipedia page. But this is a death wrongly foretold—and that creates investment opportunities.

It’s true that some malls are dying. Foot traffic is down as more Americans shop online, while shifting demographics have made malls in some parts of the country obsolete.

We estimate that a third of the 1,200 malls that were operating at the start of 2017 will close their doors, with most of the casualties in less affluent areas where population growth isn’t keeping up with other parts of the country.

Many investors have tried to profit from the shopping mall’s expected demise by betting against commercial mortgage-backed securities (CMBS) backed by loans to mall operators. Here’s the problem as we see it: not every mall is destined to close. We think plenty are likely to adapt and survive. And those that do fail won’t all do so at once.

We’ll dig into how investors can take advantage of this in due course. But first, let’s look at what the doomsayers get wrong about malls.

The Sears Fallacy

The trouble started for malls when the department stores that once served as anchors—such as Macy’s and J.C. Penney—started to close. Sears Holdings, which operates the Sears department stores that have anchored countless malls over the last 50 years, has closed more than 2,500 Sears and Kmart stores since 2005, leaving fewer than 1,000 in operation.

Some lower-tier malls won’t survive the loss of their anchor stores. But others are getting creative about replacing them—and it’s not taking as long as many people expected. For instance, the Northwoods Mall in North Charleston, South Carolina, replaced Sears with Burlington Coat Factory and Carrabba’s Italian Grill last year and saw its net operating income improve. Common anchor tenants of the future may be T.J. Maxx, Wegmans or even a car dealership.

Retailers are shifting toward online sales. Omni-channel retailers—those with brick-and-mortar stores that also sell online—convert about 5% of online shoppers into buyers, according to the International Council of Shopping Centers (ICSC). Apparel retailers are closing some brick-and-mortar stores and migrating from a sales ratio of 80%/20% in-store/online today to a target of 65%/35%.

But many want to retain a physical presence, too—with good reason. They do better with their in-store shoppers, with a capture rate of about 20% and a basket size that can be as much as seven times that of an online purchase. Those figures can still make a brick-and-mortar store profitable, despite less in-store foot traffic than in previous years. Call it the power of the impulse purchase.

Location Matters

We don’t mean urban versus suburban or proximity to a highway. When we talk about location, we’re talking about the big picture. Malls on the coasts and in the rapidly growing Sunbelt are doing well. Many in the middle of the country aren’t, especially when there are competing malls nearby.

This has everything to do with changes in demographics and the US economy. Sixty years ago, hundreds of malls sprang up in manufacturing cities like Detroit and Cleveland and their middle-class suburbs because that’s where the jobs and much of the country’s wealth were. Today, it’s high-tech metropolitan areas like San Jose, Boston and Austin that have seen big gains in population, wages and wealth.

Experience vs. Convenience

Even so, malls that have figured out how to cater to evolving consumer tastes are thriving, regardless of location. Discretionary income has been constrained by limited wage growth and by rising housing, healthcare and education costs, all of which have materially outpaced inflation in recent years. That means consumers—and millennials in particular—are making choices based on a combination of modern tastes and restricted spending decisions.

Millennial consumers tend to value experiences more than objects. That may mean they’re more likely to come to the mall for high-end dining, free in-store yoga classes or personal fitness training rather than another pair of shoes. In response, mall owners are repositioning malls away from a mix of 60%–70% apparel retailers to only 40%–50% in order to create a town-center atmosphere where consumers will come to be entertained, as well as to shop for the latest concepts in clothes, cosmetics and home goods.

In general, that means more movie theaters, sports bars, restaurants, fitness centers, interactive playgrounds and entertainment. But every mall is different and needs to reflect local demographics. For example, in areas with large Latino populations, one mall operator is replacing department stores with concert spaces, flanked by kiosks run by local importers and retailers that appeal to local consumers.

Easton, an outdoor “experiential” mall in Columbus, Ohio, is doing it all. It’s got experiential retail stores such as the American Girl store where children can design clothes for their dolls and themselves, top-end dining, a comedy club, several hotels and a planned LEGOLAND family theme park.

How Investors Can Capitalize

What does all this mean for investors? Simply put, not all malls are doomed. Some are still generating sufficient cash flow to comfortably cover their debts, making them viable retail assets today and in the future. For investors who can analyze each mall operator’s leasing strategy and credit metrics, that can lead to attractive, high-income opportunities.

Make no mistake: plenty of malls are in trouble and will close. And loss severities—the amount of missed interest and principal payments—on loans in default have been higher for mall loans than for the office building and apartment complex loans that frequently back CMBS.

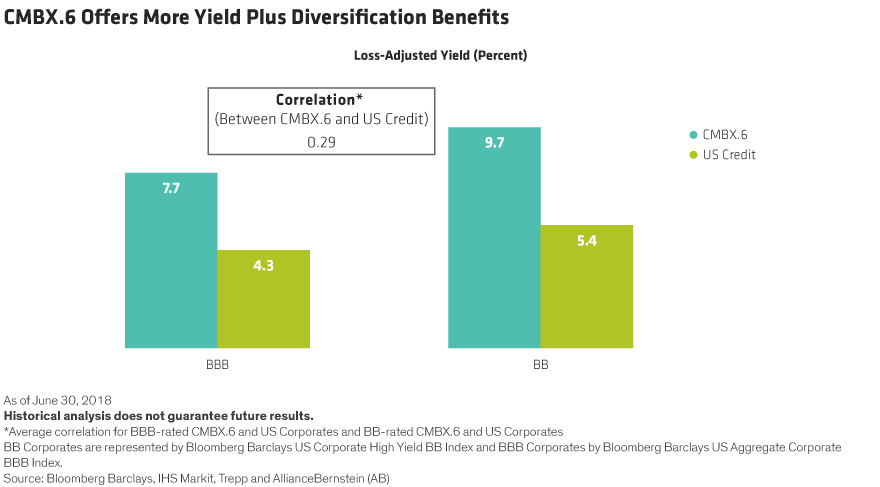

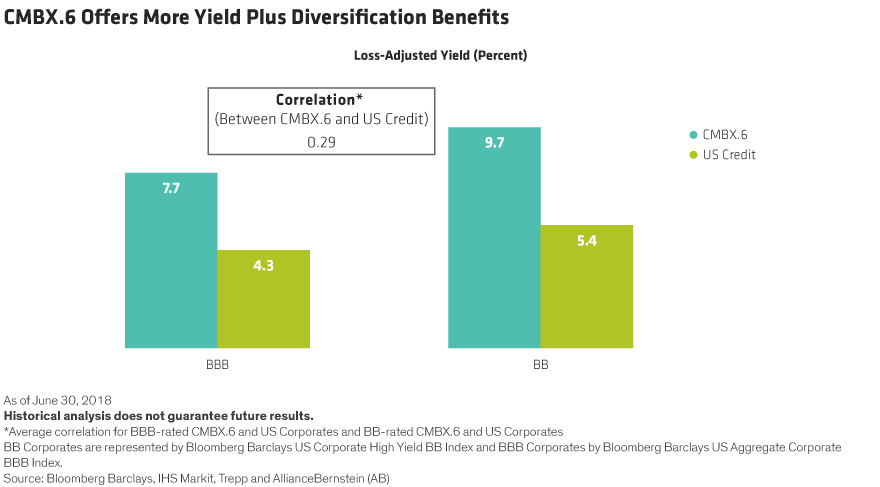

These default fears have pushed the yield spreads on BBB-rated bonds in the CMBX.6, an index tied to commercial mortgages that originated in 2012, to trade at a record premium to spreads on comparably rated US corporate bonds, creating an attractive relative-value opportunity. Even when adjusted for potential losses due to anticipated defaults over time, the CMBX.6 BBB– tranche yields nearly 8%, while the CMBX.6 BB tranche yields nearly 10% (Display).

Many investors betting on a retail apocalypse have made headlines by shorting the CMBX.6—a bet that, in order to succeed, depends on the underlying loans experiencing massive losses that unfold very soon. We think shorting the CMBX.6 is a risky strategy for several reasons.

First, the underlying mall loans will likely experience lower default severity than expected. We estimate that only six of the 42 malls whose loans are included in the index are essentially “dead malls” that will almost certainly default and liquidate close to their land value.

That level of loss severity is broadly applied by some investors across all the malls in the CMBX.6. However, the remainder of malls in the index have enough cash flow to comfortably cover their annual interest and principal payments.

In fact, the majority of malls in the CMBX.6 are not “dead malls” and still collect sufficient rent revenues to cover their by more than 1.7 times. It’s true that lower market appraisals may create refinancing issues for some of these malls, but more than 75% are owned by public REITs with access to alternate forms of capital. Also, for malls with sponsors that lack capital, foreclosure may be likely, but many of these malls still produce positive internal cash flow and are ongoing concerns. In other words, they’re not just land, so it’s unlikely they will liquidate at land value.

Second, losses will be mostly down the road—and the more distant, the better. Malls in the CMBX.6 that do default won’t do it all at once. The special servicers that work out defaulting loans work with borrowers to maximize the recovery value. They can modify loans and free up cash flow to give the operators resources to re-tenant the malls. When foreclosure and liquidation become inevitable, the special servicer can make the necessary protective advances to pay property taxes, deferred capex or leasing costs.

In those instances in which the mall simply hasn’t got a pulse, the special servicer will liquidate the asset to maximize recovery. Even then, this process takes many months.

Finally, malls are only a fraction of the CMBX.6. For example, about 60% of the loans referenced in the CMBX.6 are non-retail loans that have seen their equity rise and their loan-to-value ratios decline over the last six years as loans have amortized and rental and occupancy rates have improved. That helps to offset the exposure to low-tier regional mall loans whose loan-to-value ratios have risen.

As investors, it’s easy for all of us to get caught up in the hype around the latest big idea. But sometimes, the best strategies are the quotidian ones that target mispriced assets, missed opportunities and relative-value trades. The demise of the American mall makes for good headlines, but not necessarily a good investment strategy.

The views expressed herein do not constitute research, investment advice or trade recommendations and do not necessarily represent the views of all AB portfolio-management teams.

Copyright © AllianceBernstein